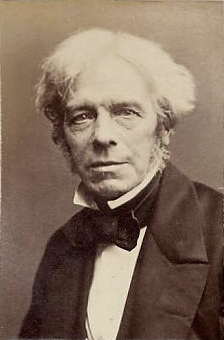

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons One of the most prolific experimenters in history, a man who had little in the way of formal education, was born on September 22, 1791 in the tiny London borough of Newington Butts. The third of four children born to a poverty-stricken Christian family, Michael Faraday would end up using his basic schooling to become a prolific student in the fields of chemistry and electricity. While still living, he published three books on his hypotheses and theories, ultimately being known for the discovery of the earth’s magnetic field, among many other achievements. Shortly before Faraday’s birth, his father James — a blacksmith apprentice in search of more opportunity — moved the family to Newington Butts in the hope London would prove a better place to launch a career. Unable to afford the cost of extended education programs, he connected Michael with a bookstore for training as a bookbinder. The younger Faraday, tied to George Riebau for a seven-year period, used the opportunity of being surrounded by volumes of information to educate himself. His interest in science piqued by books like Conversations on Chemistry by Jane Marcet, he began attending lectures at the Royal Institution of Great Britain. After spending months listening to Humphry Davy, the most highly-regarded English chemist of his day, Faraday compiled a 300-page notebook filled with his observations and sent them to the lecturer. Taking to the 20-year-old, Davy eventually brought Faraday in as a secretary after a lab accident left him with reduced vision. Two years later, when a position for an assistant in the Chemistry department opened up, Davy appointed his young protege on March 1, 1813. Focused primarily on chemistry due to his work with Davy, Faraday spent much of his day attempting to understand the nature of chlorine and its interactions with carbon. Very quickly, he discovered new compounds and began to experiment with the diffusion of gases, discovering benzene before eventually coming up with a means to produce a flame that would be refined into the Bunsen burners still used in chemistry labs at every level today. In 1821, he published his first scientific studies, detailing his creation of hexachloroethane and tetrachloroethylene. That same year, a scientist in Denmark discovered electromagnetism, which motivated Davy and a colleague to see if the force could be manipulated to create an electric motor. Faraday, intrigued with the concept after discussing the tests with his mentor, he set out to come up with a means to force the rotation needed, creating two functional designs. When he published his results and forgot to credit Davy and his associate for their contributions, Faraday offended his boss so much he was reassigned to other projects far outside the realm of electromagnetics. Focusing on chemistry during the day and filling his free time with tests of electricity and magnets using a variety of substances, Faraday happened upon mutual induction. After separate pieces of coiled wire around an iron ring, Faraday realized the current sent through one was being passed to the other. Pushing the results further, he realized he could produce an electrical charge by manipulating a magnetic field — a principle which would play a key role in his development of an early incarnation of an electric generator. Now a well-respected member of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, Faraday continued working furiously for both academic and private interests. In 1845, he noticed how polarized light bent around magnetic fields, forming the basis for an evaluation of the lines of force which exist between the opposing poles of magnetic objects. Three years later, as a matter of respect from the British Crown (whom he had rebuffed twice in requests to knight him), Faraday received a house free of charge on Hampton Court Road. In the early 1850s, as the British entered the Crimean War against Russia, the government approached Faraday with questions about the possibility of weaponizing chemical compounds. Unwilling to explore the idea, he politely stepped aside due to his concerns about the ethics of using such materials against another man. Two years after the war ended, Faraday retired to his home in 1858. In late August of 1867, he died and, once again refusing the honors others wished to give him, was buried in Highgate Cemetery instead of Westminster Abbey. Also On This Day: 1862 – The first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation is released, freeing slaves in Union-held territory. 1888 – National Geographic Magazine releases its first issue. 1896 – Queen Victoria becomes the longest-reigning British monarch. 1941 – The SS brings the total number of Jews killed in Vinnystya, Ukraine to 30,000 in just a few days by killing 6,000 on Rosh Hashanah. 1965 – The Second Kashmir War ends when the United Nations calls for a cease-fire between India and Pakistan.

eptember 22, 1791 CE – English Scientist Michael Faraday is Born

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons One of the most prolific experimenters in history, a man who had little in the way of formal education, was born on September 22, 1791 in…