Following 39 days of tense discussion fraught with international implications, Palestinian militants and Israeli officials finally agreed to end the Siege of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem on May 10, 2003. The Church of the Nativity is a basilica significant to both Christianity and Islam, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site — the threat of its destruction loomed large over the faithful throughout the world. With the situation brought to a relatively peaceful conclusion, the conflict over the West Bank turned the page on another chapter in its checkered history. In 327, the Roman Emperor Constantine — the first official Christian ruler in Europe — ordered the construction of a church on the purported site where Jesus of Nazareth was born. The project, overseen by his mother and fellow-believer Helena, resulted in a comparatively small but ornate basilica built on the ground above a revered cave referred to as the “Grotto in Bethlehem”. Consecrated by the Bishop of Jerusalem in 339, six years after it was completed, it is widely regarded as the longest-operating Christian church in the world. Though burned to the ground during the Samaritan Revolts of the late 5th and 6th centuries, a second iteration of the classic church took shape in 565. Over the centuries, the Church of the Nativity tripled in size, with successive kingdoms of different religious persuasions — Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Islamic — adding square footage and bell towers in order to accommodate the vast numbers of Christian and Muslim pilgrims who visited each year. Ever since the creation of the Jewish State after World War II, there have been numerous confrontations between the displaced Palestinians and the Israelis. In the last six decades, there have been three full-scale Arab-Israeli wars and two Intifadas — uprisings instigated by groups seeking Palestinian liberation — as well as countless smaller actions between the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and Palestinian militant freedom fighters. For many, both inside and outside the region, the constant threat of violence is merely a part of life. When the Second Intifada began in September 2000, it almost seemed a natural consequence of growing pains in the wake of the Oslo Accords signed during the 1990s. The Israeli administration and Palestine authorities both pointed fingers at the opposition as disputes arose over who violated construction agreements made in the Norwegian capital prohibiting fresh Palestinian or Israeli settlements in certain areas of the West Bank. Discussions during the Camp David Summit, the previous July, were hardly fruitful and, according to some, Palestinian President Yasser Arafat ordered the Intifada in order to force the IDF to attack, thereby swinging global opinion in favor of his interests. The accusations remain unproven, yet the fact remains that two organizations known for suicide missions on Israeli military and civilians, Fatah and Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, went to work late in the summer. During Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s trip to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem on September 29, a riot incited by Aqsa operatives greeted him. Within a week, dozens of Palestinians were dead and nearly 2,000 wounded. In the coming days, a variety of actions against the Israelis — everything from haphazard protests to highly-organized military assaults — resulted in heightened security throughout the West Bank. For 18 months, the two sides engaged in a back-and-forth struggle between diplomacy and aggression. Hundreds ended up dead and thousands were injured. Fed up with another wave of suicide bombings, Sharon and his cabinet announced the launch of Operation Defensive Shield on March 29, 2002. More than 30,000 IDF reservists were called in to boost the ranks of the Israeli infantry, giving strategists the option to launch a more sophisticated action in Palestinian territory. By the first week of April, movements into Bethlehem, Jenin, Nablus and Ramallah were underway. On April 2nd, the IDF Paratroopers Brigade dropped into Bethlehem supported by tanks surrounding the town. Knowing militant Palestinians had used the Church of the Nativity as a safe haven in the past, commanders hoped to position soldiers around the site undetected, thereby allowing the IDF to blockade the holy building. Despite the best intentions, the Israelis arrived a half-hour too late — 39 Palestinians suspected of operating on behalf of Fatah, Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad were already inside the church. Heavily armed and holding the 200 monks on site hostage, the militants counted on the food supply and deep freshwater wells within the church to help them survive a long-term blockade by the IDF. By the morning of April 3, 2002, tanks were near Manger Square and snipers were targeting anyone moving inside the church. Sensitive to the site’s obvious religious importance, Israeli Brigadier General Ron Kitri went on record saying the use of weapons that could damage the church would be a last resort. “There are several channels of negotiation to try to achieve as close to a peaceful solution as possible,” he said, while still authorizing soldiers on the ground to take action if the opportunity existed. Four days later, April 7th, officials from the Roman Catholic Church began applying pressure on the Israeli government. Citing the Christian desire to provide care for anyone so long as they were unarmed, Pope John Paul II called the fighting “unimaginable and intolerable.” For almost three weeks, the IDF and Palestinians stood at a virtual standstill, with diplomats from a number of Western nations questioning Sharon’s strategy. Finally, serious discussions between the two parties on a settlement began on April 24. A two-week-long bargaining session allowed for the periodic release of hostages and a few militants. Intense discussions with other countries — Italy and Spain, in particular — allowed the Israelis to agree that some of the Palestinians could be exiled to Europe instead of arrested. On May 10, 2002, the final 13 Palestinians assented to meeting British Ambassador Sherard Cowper-Coles and a squad of Royal Military Police. The Siege of the Church of the Nativity was over with relatively little damage to the structure, giving the faithful all over the world cause for a sigh of relief. In total, 8 of the Palestinians fell victim to IDF sniper bullets and one civilian, an Armenian monk, was wounded. As Israeli police swept the site, they recovered some 40 booby-trapped explosives undetonated. Considering the worst case scenario, the fact only $77,000 worth of damage had been inflicted on the church — most of it due to a fire both sides claim the other started — was a miracle. More than a decade later, pockmarks on the exterior where bullets were fired serve as a reminder of the harrowing episode. Also On This Day: 1497 – Italian cartographer and explorer Amerigo Vespucci sets off on his first voyage to the New World. 1801 – Tripoli’s Barbary Pirates declare war on the fledgling United States of America. 1948 – President Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China institutes “Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion” that last until April 30, 1991. 1960 – The USS Triton nuclear submarine completes an underwater circumnavigation of the globe, codenamed Operation Sandblast. 1994 – Nelson Mandela is inaugurated as the first Black President of South Africa.

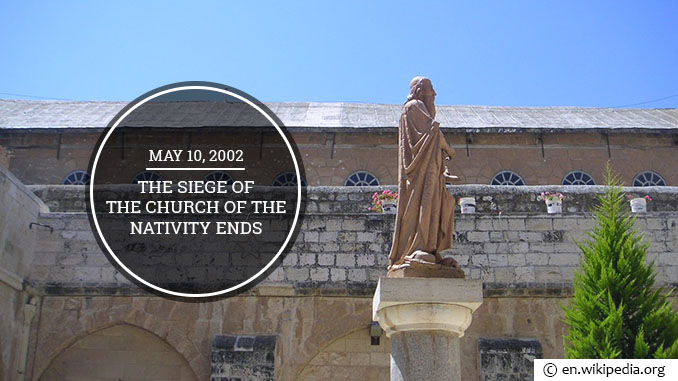

May 10 2002 – The Siege of the Church of the Nativity Ends

Following 39 days of tense discussion fraught with international implications, Palestinian militants and Israeli officials finally agreed to end the Siege of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem on…