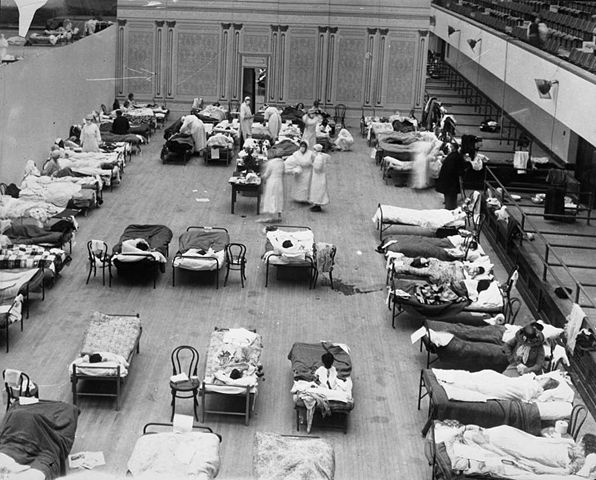

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Albert Gitchell, a young cook in the United States Army stationed at Fort Riley in northern Kansas, reported to a military hospital on March 4, 1918 complaining of a fever. In diagnosing Gitchell with a virus, doctors were unaware of the significance of the find: the patient had the first confirmed case of Spanish flu, one of the deadliest illnesses in the history of the world. With World War I raging in Europe, hundreds of thousands of men from all over the planet converged to fight on behalf of the Triple Entente or Central Powers. Soldiers from every inhabited continent engaged in combat, with a large percentage fighting in Western Europe. Packed into tight quarters, troops spent months at a time next to each other, battling the elements almost as much as the enemy. Slipping into the lungs of infected individuals, the flu is easily spread through the air. Coughs and sneezes — even a simple conversation — provide the virus an opportunity to find another place to rest and reproduce. Further, the bug can survive on surfaces for several hours after first being transmitted, meaning a doorknob or ink pen can turn into a vehicle for passing the illness from one person to the next. Unlike bacteria, a virus requires host cells in order to be effective. As it invades a potential victim, the virus injects its genetic material into an otherwise healthy cell, transforming it into a rapidly-dividing threat to the health of the individual. If the virus is able to replicate on a large enough scale before the body can mount a defense, sickness results. With thousands of men in such close proximity on both sides of No Man’s Land in western France, many of them malnourished due to poor supply during the harsh winter months and stressed by the realities of war, the virus found a fertile field to plant itself in. In January 1918, Loring Miner, a doctor in Haskell County, Kansas, reported to the US Public Health Service about a series of symptoms reflecting a particularly violent illness grabbing hold of his patients in the rural farming community he served. Two months later, Gitchell walked into the medical clinic on March 4, 1918 reporting similar issues. A week after that, he had more than 100 soldiers for company and the first cases were being described in faraway Queens, New York. With the use of trains and ships for transportation by soldiers and civilians alike increasing rapidly, not to mention the large populationin of burgeoning urban areas, people became sick at an alarming rate. Men returning from tours of duty in Europe were inadvertently spreading the virus to every corner of the globe. Within months, tens of millions were suffering. For many nations facing widespread cases, news embargoes created by the secrecy needed for military action left the illness underreported. In Spain, a militarily neutral nation during World War I, there were no such restrictions on journalism. After the virus moved southwest from battle-worn France, newspapers carried stories about the outbreak, leaving many to believe the Iberian Peninsula to be the origin, resulting in the name “Spanish flu.” What made this particular strain of the virus so effective against humans was its ability to mutate fast. Though the exact cause and starting point for the Spanish flu is a point argued to this day, some believe transmission from birds to pigs and then humans is the likely mechanism. Once in humans, the virus adapted to be more powerful with each passing week, gaining potency that allowed it to seize infected patients with heavier fevers and pneumonia by August 1918. And, curiously, it was most effective among those who doctors expected to have the easiest time fighting it off, those aged between 18 and 49 — the age of servicemen returning home from World War I in droves during the autumn of 1918. The medical community was completely unprepared for the illness to hit: no vaccines or antiviral medications existed — and, to compound the problem, municipal policies for quarantine were relatively undeveloped. As the stronger Spanish flu came into full force, cities and towns all over the world had no plans in place to handle the large patient loads while sequestering the sick. Hospitals were suddenly overflowing with people coughing and feverish, with staff overwhelmed — even medical students were pulled into the wards to help provide care. By the end of the year, officials in affected cities were turning schools, theaters and churches into makeshift clinics to treat the additional patients. Those with enough courage to venture outside were encouraged to wear masks to prevent further infections. Local administrators were willing to try anything to keep the illness from getting worse. In New York City, for example, the health commissioner ordered businesses to open and close in shifts to reduce traffic on the subways. Then, almost as quickly as it appeared, the Spanish flu seemed to diminish into a minor sickness. (Most viruses become weaker with more exposure.) What had threatened the entire population of the world one month soon petered out, with reported cases ending by the middle of 1919. With the vast number of deaths related to the intense fighting of World War I, it is difficult to be sure how many people were killed directly by Spanish flu. Authorities estimate as many as half a billion people were infected at one point, with anywhere from 20 to 50 million — as much as 3 percent of the world’s population at the time — killed. In some smaller nations of the South Pacific, such as Western Samoa, vast percentages of residents were infected and the country was nearly wiped out. Beyond the death toll, societies were affected economically and psychologically. With so many people sick and unable to work, production in a variety of industries was hampered significantly. Agriculture in the United States, in particular, faced shortages due to a lack of able-bodied workers for planting and harvests. On top of that, fear of infection left some so paralyzed with dread they would not leave their homes for months. Of the half-dozen major flu outbreaks since 1918, the Spanish flu was ten times as deadly as the worst of them and killed at least four times as many people as those that came after it combined. Ninety years later, researchers studying the structure of Spanish flu realized the effects of the illness were so dramatic due to its ability to weaken the bronchial tree within a patient’s lungs. The resulting susceptibility to pneumonia — the infected were unable to cough strong enough to eject mucus — led to increased severity and caused the majority of deaths. Also On This Day: 1152 – Frederick Barbarossa becomes King of the Germans 1519 – Hernan Cortes arrives in Mexico to search for the wealth of the Aztecs 1776 – The Continental Army places cannon on Dorchester Heights, setting up a major victory early in the American Revolutionary War with the Siege of Boston 1899 – Cyclone Mahina causes a 39-foot wave to strike Cooktown, Queensland, Australia and kills 300 1918 – The USS Cyclops leaves Barbados days before disappearing, presumably in the Bermuda Triangle

March 4 1918 – The First Case of Spanish Flu is Reported at Fort Riley, Kansas

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Albert Gitchell, a young cook in the United States Army stationed at Fort Riley in northern Kansas, reported to a military hospital on March 4, 1918…