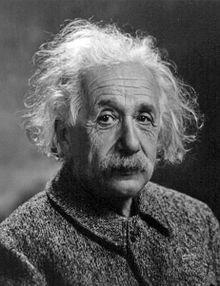

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons In the town of Ulm, a picturesque city on the Danube River in southern Germany, one of the world’s most brilliant minds and famous faces was born on March 14, 1879. Albert Einstein, as well-known for theories that turned science inside out as for his trademark shock of white hair, would rise from his middle class roots to affect human understanding of the universe on a large scale. Within a few months of Einstein’s birth, his family moved to Munich so his father and uncle could build a business manufacturing electrical machines built on direct current. Hermann, Einstein’s father, used his expertise as an engineer and sales acumen to help the company grow quickly, earning enough to send his son to a private elementary school. Intensely curious, the young boy did well in class, gaining admission to the Luitpold Gymnasium at the age of 8 for more challenging instruction. As the years passed at Luitpold, Einstein demonstrated tremendous potential in mathematics and engineering, creating small devices in his free time. Fascinated with the way things worked, he spent hours poring over books about science and math, pursuits he enjoyed as much as music and philosophy. By his teens, he had become proficient playing the violin and piano, an artistic extension of his ability to rapidly parse fractions in his head. At the age of 15, events conspired to throw Einstein’s life into turmoil: Hermann’s business collapsed when the effectiveness of alternating currents like those created by Nikola Tesla was proved. The factory was shuttered almost overnight. Forced to move in order to find employment, Hermann took the family to Italy and left Einstein behind to finish his studies in Munich. Left to himself, the teenaged boy increasingly expressed his doubts about the style of teaching at Luitpold and decided to join his family in Pavia in early December 1894. Even though he was a drop-out, Einstein was convinced he could gain entry into the prestigious Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich (SFP) on raw ability. He took entrance exams in the summer of 1895, testing well in math and physics but coming up short in everything else. Perhaps seeing potential in the young German, the school’s administrator directed Einstein to finish his education at a nearby secondary institution before making another attempt. The next year, Einstein passed the Matura exit exam and entered SFP intent on becoming a teacher, brushing off his father’s hope he would choose a career in electrical engineering. Upon receiving his diploma in 1900, he anticipated putting his four years’ worth of education to use right away. Things did not work out as Einstein wanted: despite inquiring throughout Europe, he could not secure a professorship or lecturer position anywhere. Taking a job as a patent clerk in the Swiss city of Bern, Einstein spent his days reviewing applications and scribbling down his thoughts whenever he could. Frustrated to be an assistant examiner instead of fulfilling his wish to teach, his mind often wandered into thought experiments about the nature of light, possibly inspired in part by the electrical devices he looked at every day. Bored by his job, Einstein focused his efforts on the ideas of Scottish physicist James Maxwell he learned in school. In looking over Maxwell’s equations and their descriptions of light, Einstein continuously found an inconsistency. Toying with the information further, Einstein realized he had discovered the speed of light (c) remained constant — something Maxwell failed to identify. Spurred by the concept of a strictly-defined velocity, he worked diligently to quantify his ideas. While doing this work, he wrote out E=mc2, the world’s most famous equation. The year 1905 provided the big break Einstein needed. He completed his doctoral thesis, receiving a PhD from the University of Bern for his dissertation “A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions.” On top of that, he published four articles in Annalen der Physik, a respected journal he previously helped to review after submitting his first paper in 1901. The central themes of each of the articles caused immediate controversy: Einstein had undermined — maybe even destroyed — physics as described by the venerated Sir Isaac Newton. Considered his “Miracle Year,” 1905 is regarded as one of the most important in the history of physics simply based on Einstein’s conclusions. With his first paper, he proved the photoelectric effect proposed by Max Planck, demonstrating light existed as waves of tiny packets called quanta. In his second, Einstein described Brownian motion in a way that showed atoms — long believed to be just a theory — existed as a reality. The third, the special theory of relativity, posited all other measurements were related to c, the constant speed of light. To close out his amazing string of successes, he made the assertion the energy in an object is equal to its mass multiplied by c squared (E=mc2), creating a method to predict how much energy would be released by nuclear reactions. Now a famous academic, he finally received a teaching position, joining the physics faculty at the University of Bern in 1908. He moved on to the University of Zurich the next year, where he remained until receiving a full professorship in Prague at Karl-Ferdinand University in 1911. Believing his work up to that point applied only to “small things” — atoms and quanta — Einstein spent much of that year working on general relativity. Certain the idea would affect larger “systems” due to its description of the effects of gravity, Einstein proposed light could be bent using the force exerted by the Sun or other massive objects. If this were true, the twinkle of a distant star would change color slightly as it passed behind the Sun. It would take 8 years and a solar eclipse for him to be proved correct, but Einstein’s theory once again brought attention from all over the world. The Times of London stated the effects of general relativity simply on November 7, 1919: “Revolution in Science — New Theory of the Universe — Newtonian Ideas Overthrown.” With many in the science community still dubious about his findings, Einstein struggled to find respect for his ideas. Anything related to relativity was treated with suspicion while it awaited experimental confirmation, which left it outside the reach of prestigious awards for discovery until the late 1930s. The photoelectric effect, however, would earn Einstein the Nobel Peace Prize for Physics in 1921, but even that was greeted coldly. (The next year, winner Niels Bohr would claim “The hypothesis of light-quanta is not able to throw light on the nature of radiation” despite proof Einstein’s observations were accurate.) Einstein spent much of the next year traveling the world, treated as a celebrity wherever he went. Though a theoretical physicist — a term few in the media understood at the time — most acted as though he was a conquering king. Upon his return to Germany, he continued working as an academic until the rise of the Nazi Party made life in his homeland untenable. In October 1933, resolved to avoid returning to his homeland due to a bounty for his life, Einstein accepted a position at Princeton University in New Jersey, where he would live for the rest of his life. After years as the outsider, Einstein transformed into the resolute “old head” in physics while in New Jersey. Determined to disprove quantum theory as proposed by young physicists like Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schroedinger, he set his mind on a unified field theory, a self-described “theory of everything.” He spent the rest of his life making an attempt to pull general and special relativity together with Newtonian physics, ultimately failing. Shortly after Einstein arrived at Princeton, the Nazis began quickly advancing through Europe. Though he regarded himself as a “militant pacifist,” he realized the Germans would use their military might without remorse. When alerted to the possibility of a nuclear weapon at Adolf Hitler’s disposal by his former student, Leo Szilard, Einstein wrote a famous letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt encouraging him to pursue the Manhattan Project. Uneasy about the use of his theory to produce such a powerful weapon, he confided his regret the bomb was ever made in others, despite the likelihood it was inevitable that someone would. In the last decade of his life, Einstein remained a celebrity. He puttered around Princeton discussing his ideas with others and offering his opinions on their research, often using his fame to bring attention to injustices all over the world. On April 17, 1955, he was rushed to the hospital with internal bleeding from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, where he died at the age of 76. During Einstein’s funeral, Robert Oppenheimer, the renowned physicist at the head of the Manhattan project, eulogized the world’s most famous scientist in this way: “There was always with him a wonderful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn.” With his charming sense of humor and breathtaking intelligence — not to mention distinctive hairstyle — Einstein remains one of the most intriguing figures in modern history. As a mark of his effect on the world, TIME magazine named him “Person of the Century” in 1999. Also On This Day: 1590 – The Huguenots score a major victory over the Catholic League at the Battle of Ivry in the French Wars of Religion 1647 – Bavria, Cologne, France and Sweden sign the Truce of Ulm, creating a short-lived peace in the Thirty Years’ War 1794 – Eli Whitney is granted a patent for the cotton gin 1903 – The United States Senate ratifies the Hay-Herring Treaty, giving the US rights to build the Panama Canal 1964 – Jack Ruby is convicted for the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald, presumed assassin of John F. Kennedy

March 14 1879 – Albert Einstein is Born

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons In the town of Ulm, a picturesque city on the Danube River in southern Germany, one of the world’s most brilliant minds and famous faces was…