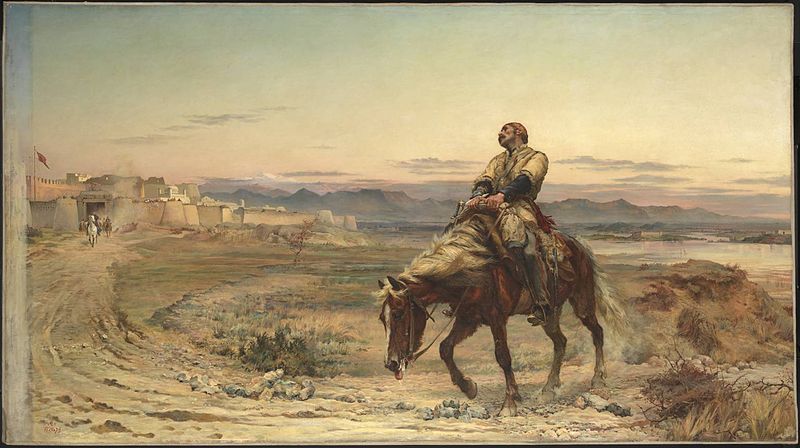

In the midst of the First Anglo-Afghan War, residents of Kabul — the modern capital of Afghanistan — rose up against the British colonial government late in 1841. When General William Elphinstone failed to bring the military advantages of his professional army to bear on the rebels under Akbar Khan, a single man was able to escape to rejoin his compatriots at Jalalabad on January 13, 1842. The arrival of Dr. William Brydon, wounded and delirious, cemented the magnitude of the embarrassing defeat. The conflict began in 1838, when the Russians increasingly came into Afghan territory from the north to strengthen ties with regional leader Dost Mohammad Khan. Though Dost Mohammad continued to play both sides, insistence by George Eden, Lord Auckland — the Governor-General of India — on British primacy over tribal dealings in the area drove the Afghan leader to side with the Russians. Furious, Lord Auckland opted to back Shuja Shah and build an army to attack Kabul near the end of the year. As the Himalayan snows thawed the following March, the British force gathered in India to pass through the Bolan Pass for the 300-plus-mile journey to Kabul. Through five months of fighting, Lord Auckland’s armies captured Kandahar and Ghazni on the way to a quick conquest of their intended target by early August. A year later, Dost Mohammad would be in British hands. Nestled between the Hindu Kush mountains and the Kabul River, the city became a picturesque locale for the British soldiers and their families. Observing the enjoyment of the occupying force, resentment among the Afghans remaining in Kabul simmered. Administrators in India, put off by the expense of dispensing protection money to nearby tribes in addition to paying troops within Kabul itself, decided the bribes would have to come to an end. Left without a reason to maintain relations with the British, locals became increasingly hostile throughout 1841. William Macnaghten, seemingly oblivious to the depth of unrest surrounding him, passed it all off as typical of the back-and-forth between tribal leaders. Even worse, he replaced the decorated officer Willoughby Cotton in favor of installing the less experienced — and somewhat sickly — Elphinstone at the head of the reduced force protecting British interests in Kabul. On November 2nd, Afghan leader Akbar Khan called for a full-on rebellion. Running rampant through the streets of Kabul, natives murdered a British official and gathered weapons from storehouses within the city. Elphinstone did not authorize a response, giving the Afghans the confidence to continue attacking, eventually firing into the British camp outside town from a hilltop secured by the end of the month. Macnaghten, suddenly awakened to the dire straits he and his fellow Brits were in, contacted Akbar Khan in the hopes of bargaining for the lives of the 12,000 people under his care in and around Kabul. As he and his associates walked toward the meeting, Afghans grabbed hold of the men and killed them. There would be no discussion of a peaceful withdrawal. (As if to prove the point, Macnaghten’s remains were pulled through the streets.) Once again, Elphinstone shrank from the moment, choosing to surrender on January 1, 1842 and move the British soldiers and their support out of town five days later. Believing the group would be left alone on the trek to Jalalabad 90 miles to the east, he led the column out into the snowy mountains with little food or supplies — resources promised by Akbar Khan. Laboring to move through the valley with thousands of civilians as part of the contingent, Elphinstone and his soldiers were under attack from all sides, resulting in an average of 1,000 deaths each of the first three days of the retreat. With each passing day, more British were killed or captured. Many of the Indian troops and civilians employed as support were slaughtered. Only one man, Dr. William Brydon, managed to reach the garrison at Jalalabad. Arriving with an open skull and riding a wounded horse on January 13, 1842, he was asked where the army was. “I am the army,” Brydon replied. The image of the lone rider nearing safety would later be made famous by Elizabeth Butler in her painting Remnants of an Army. Ashamed of and shocked by the result, the British mounted an army for retaliation nine months later. Angered by the treatment of the soldiers and civilians by the Afghan tribesmen, the troops stormed through Kabul with revenge on their minds. Of more than a hundred Brits freed by the raid, Elphinstone could not be counted — he died of illness in late April. Also On This Day: 1785 – The first issue of the Daily Universal Register, forerunner to The Times of London, is published 1847 – The Mexican-American War comes to an end with the Treaty of Cahuenga 1898 – J’accuse by Emile Zola exposes the anti-Semitism behind the Dreyfus Affair in France 1910 – A live performance of Cavalleria rusticana at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City becomes the first public radio broadcast 1942 – Tests in Germany begin on the first ejector seat for aircraft in a Heinkel He 280 jet You may also like : January 13 1898 – J’accuse By Emile Zola Exposes The Anti-Semitism Behind The Dreyfus Affair in France

January 13 1842 – Dr. William Brydon, Survivor of the Massacre of Elphinstone’s Army, Reaches Jalalabad

In the midst of the First Anglo-Afghan War, residents of Kabul — the modern capital of Afghanistan — rose up against the British colonial government late in 1841. When General…