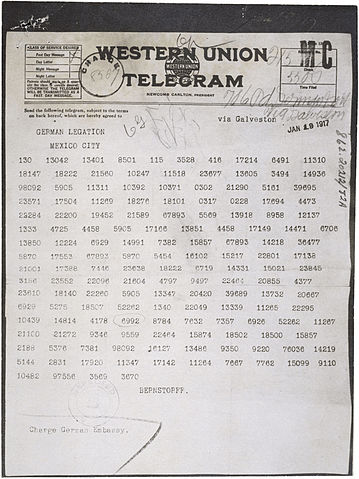

Eight days after British intelligence officers decoded a transmission between German diplomats, President of the United States Woodrow Wilson received the text of a transatlantic cable on February 24, 1917. Detailing plans to return the US Southwest to Mexico in exchange for cooperation with Germany in World War I, the Zimmermann Telegram exposed espionage that increased German-American tensions. When the letter was made public a week later, the message would turn sentiment completely against the Germans and accelerate the charge to a declaration of war. Since conflict broke out among the European nations in July 1914, American leadership had been painstakingly cautious to avoid intervening on either side in World War I. Two-and-a-half years later, Wilson’s administration found it more and more difficult to keep the US from getting involved — the sinking of the Lusitania, for example, swayed public opinion toward action. With the Germans struggling to overcome advances on both fronts, backroom discussions about the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare progressed to the point a new round of attacks seemed inevitable by mid-January 1917. Strategists realized unleashing the U-boats once again would bring the US into the war opposing Germany, so Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann sent a message to Heinrich von Eckardt, the ambassador to Mexico, on January 16th. How the telegram was discovered, though, makes the story all the more intriguing: Zimmermann’s coded instructions were sent over American telegraph lines. Within months of the beginning of World War I, the British cut the transatlantic cables linking Germany with the Western Hemisphere, cutting Berlin off from its embassies in North and South America. As a goodwill gesture, Wilson offered to allow some transmissions to be made through a network of US ambassadors to the German officials on the other side of the ocean. Once Kaiser Wilhelm II signed off on the plan to let U-boats hunt in shipping lanes beginning February 1st, Zimmermann sent the message — a complex, numerical readout as opposed to the promised “clear” text — through these established channels. Unknown to either Germany or the US, British intelligence agents were eavesdropping on the cables. At the infamous Room 40 in the offices of the Royal Navy, codebreaker Nigel de Grey formed a partial transcription of the Zimmermann Telegram within hours. Victories in Mesopotamia and at sea over the SMS Magdeburg gave the British military access to a pair of key ciphers used by German officials, creating a further strategic advantage, one which Room 40’s chief, Admiral William Hall, was reluctant to disclose. Over the next three weeks, de Grey and another staffer fully decoded the message. Hall, wary of the appearance of impropriety toward the US, passed the information on to the British Foreign Office two days after Wilson ended diplomacy with Germany on February 3rd. (The move was a protest of the new U-boat attacks.) In order to preserve relations with the Americans and protect their knowledge of German encryption, British officials worked diligently to create plausible cover stories. Settling on tales of bribery and theft, Hall showed the translated message to Edward Bell at the US Embassy in London. The next day, ambassador Walter Page received a copy. The text was explosive: Zimmermann instructed von Eckardt to approach the Mexican government with an offer of financing for a war effort against the United States, as well as the recovery of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona following a victory. In addition, von Eckardt was to impress upon the Mexican President, Venustiano Carranza, the need to bring the Japanese government in on the same side. On February 24, 1917, Wilson received word of the telegram from British officials. A week later, Zimmermann’s words were all over the American press. Almost all of the remaining anti-intervention sentiment in the US quickly evaporated. When Zimmermann admitted the telegram was not an elaborate forgery on March 3rd, public opinion shifted toward the necessity of war. The German audacity to transmit such a blatantly aggressive message over American cables, in addition to the inflammatory content itself, flared anti-German and anti-Mexican thought. (Carranza, for his part, was quickly advised by one of his generals that Zimmermann’s words were “empty promises.”) Six weeks after receiving the Zimmermann Telegram, Wilson stood before Congress on April 2, 1917 to make the case for entering World War I on the side of the Triple Entente. Four days later, the House of Representatives passed the resolution by a vote of 373 to 50, with the Senate affirming the declaration by a margin of 82 to 6. The US, long delayed, was finally set to enter the Great War. Also On This Day: 303 – Emperor Diocletian calls for persecution of Christians throughout the Western Roman Empire 1582 – Pope Gregory XIII announces the Gregorian calendar 1848 – King Louis-Philippe of France abdicates the throne 1920 – The Nazi Party is founded in Munich, Germany 2008 – Fidel Castro announces his retirement as President of Cuba You may also like : February 24 1920 – Hitler launches the twenty-five point program of the Nazi Party in Munich, Germany

February 24 1917 – The Zimmermann Telegram is Passed to the United States by British Authorities

Eight days after British intelligence officers decoded a transmission between German diplomats, President of the United States Woodrow Wilson received the text of a transatlantic cable on February 24, 1917.…