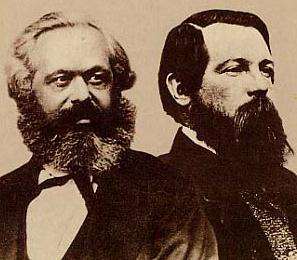

Striking out against the burgeoning capitalist systems in Europe and North America, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published one of the world’s most-read political manuscripts on February 21, 1848. Commissioned by the Communist League based in London, The Communist Manifesto outlines a form of government designed to distribute wealth and eliminate social strata, for, as Marx and Engels wrote: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” In June 1847, a group of men from two separate organizations met to discuss common ideas. The League of the Just, formed by a handful of Paris-based Germans built on “the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth,” connected with the Communist Correspondence Committee from Brussels. Marx and Engels were active in the latter, influencing the Belgian branch of the Committee and, in turn, affecting the larger German Communist movement. Just getting the men around a table had taken six months, but the thrust of the meeting would be a decision on the primary principles of the party’s political aims. Karl Schapper, a key figure among the League of the Just, impressed upon Engels the need for his and Marx’s thoughts to shape the Communist League’s agenda. Having been exposed to their ideas through columns in the Deutsche Bruesseler Zeitung, a German-language newspaper in Brussels, Schapper believed his two fellow Germans could give the League a sort of verbal structure — what the primary philosophy should be, how capitalism failed so many and the method by which to change it all. When Engels officially became a member of the League in July 1847, leadership asked him to create a formal declaration of basic points everyone interested in joining the party could adhere to. His early drafts would become The Principles of Communism, the backbone of Manifesto. By late fall, Marx had gained entrance to the group, as well. At the end of the League’s second meeting, in December 1847, Schapper got his wish and Marx and Engels were formally given the task of writing the founding document. According to Engels’ own account, Marx spent the next two months scouring The Principles and reading through The Condition of the Working Class in England, another of Engels’ writings. From there, Marx added his thoughts to form a solid narrative — much like a speech to be delivered in a town square — such that “the greater part of its leading basic principles belongs to Marx,” Engels later wrote. Though it is difficult to discern how much philosophical weight Engels brought to bear during the process, one thing is certain: he is the one who gave the document its name, citing the force of the word “manifesto.” Following approximately two months of work, Marx and Engels submitted the final manuscript to some of their fellow political refugees in London, who promptly published it in German on February 21, 1848 and saw that it was serialized in a local German newspaper. Detailing the reasons why capitalism led to tension between the well-to-do bourgeoisie and the hard-laboring proletariat, Marx and Engels suggested the working class would soon rise up to overthrow their oppressors — hence the League’s slogan (borrowed from Marx): “Workers of the world, unite!” Once the first domino in this revolution fell — likely Germany, Marx and Engels believed — nation after nation would soon erupt in a final class struggle which would redistribute private property evenly amongst the masses. Little did they know, the battle they predicted was already underway. In January 1848, hundreds of Sicilian civilians rose up against Bourbon rule on their island in the Mediterranean Sea. Three days after Manifesto was published, February 23rd, riots broke out in France. Germany would see demonstrations next, followed by Denmark and nearly a dozen nations — some as far away as South America. Members of the League returned to Germany to participate in the changes as part of The Workers’ Brotherhood, drawing attention to the once-secret society. When the revolutions fell apart and the status quo was restored, the Manifesto drew more attention to the League, as well as to Marx and Engels. While leadership argued for months about the future direction of the organization, Wilhelm Stieber — a spy employed by the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck — slipped into Marx’s home and made off with the membership rolls. The governments of France, Prussia and Germany soon had several active participants in jail, with seven of the eleven accused by the Prussians ending up behind bars for six years. It was November 1852 and it seemed as if Communism had already come to an end. Marx would live out his days in London after being forced to leave Germany and France. Still, more than a century and a half after its first publication, The Communist Manifesto has a bewildering power over readers. The ideas espoused by Marx and Engels reflect a prescience few works can claim, as the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011 often pointed to the same differences in class Marx touched on 163 years before. Also On This Day: 1804 – The first self-propelling steam locomotive debuts at the Pen-y-Darren Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales 1878 – New Haven, Connecticut receives copies of the world’s first telephone book 1885 – The Washington Monument is dedicated 1945 – Kamikaze attacks sink the USS Bismarck Sea and damage the USS Saratoga near the island of Iwo Jima 1972 – President of the United States Richard Nixon visits China You may also like : February 21 1972 – President of the United States Richard Nixon visits China February 21, 1848 – Communist Manifesto is published

February 21 1848 – The Communist Manifesto is Published for the First Time

Striking out against the burgeoning capitalist systems in Europe and North America, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published one of the world’s most-read political manuscripts on February 21, 1848. Commissioned…

February 21, 1848 – Communist Manifesto is published

February 21, 1848 – Communist Manifesto is published