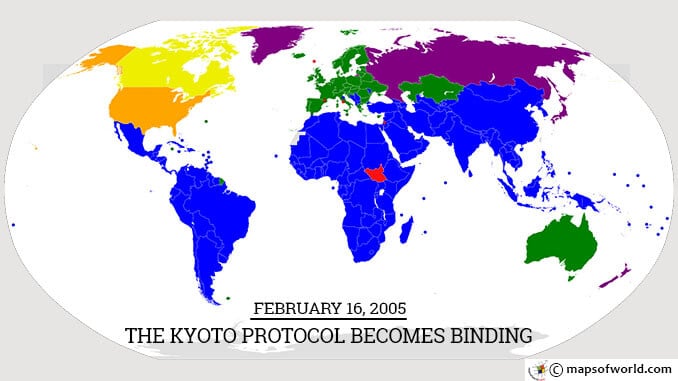

World map of countries who singed kyoto Protocol In a bid to bring the world’s industrialized nations under one umbrella to slow global warming, the Kyoto Protocol was signed by 83 nations near the end of 1997. Officially part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the environmental treaty came into effect officially on February 16, 2005 when Russia ratified the agreement. The years since have seen a number of twists and turns in the saga to minimize human effects on Mother Nature. As early as the middle of the 20th century, scientists began to study the effects of human industry on the larger environment. Noticing an appreciable rise in the average temperature worldwide from year to year, researchers posited Earth would face significant changes in weather patterns for generations to come, raising ocean levels and creating extreme climate conditions all over the globe. In 1985, members of the diplomatic community gathered in Vienna, Austria to discuss the discovery of a thinning in the ozone layer above Antarctica. Reviewing findings of more UV-B radiation filtering in above the South Pole, 28 nations agreed to the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and a further 169 ratified it later — all the members of the UN and even smaller principalities like the Vatican. Two-and-a-half years later, a further definition of the substances affecting the atmosphere was agreed to with the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Once again, UN membership gave its full-throated support to the treaty phasing out the use of cholorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). Through a series of revisions, the standards against CFCs and HCFCs were clarified, with a baseline level of emissions for all “greenhouse gases” created in 1990. In an attempt to tamp down the negative effects of industrialization even further, 37 countries and representatives from the European Union gathered in Kyoto, Japan to create an international treaty committing to measurable reductions in the emission of comparable carbon dioxide equivalents. Using the standards agreed to on December 11, 1997, release of methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexaflouride, perfluorocarbons and HCFCs would all be converted to similar levels of carbon dioxide production and then regulated to the point of “stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” In other words, by creating a system which held nations accountable to each other for worldwide reductions of 5.2 percent per year, UNFCCC believed climate change would return to being a merely natural phenomenon, if it existed at all. In addition, the Protocol established the possibility for what are today referred to as “cap-and-trade” incentives for reducing pollution and “carbon credit” programs that allow high-emitting entities to invest in developing nations with the intent of, say, planting trees to offset the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. These “flexible mechanisms” made the Protocol more attractive to a variety of nations, particularly those inflicted with heavy poverty, eventually bringing it into force when Russia ratified the agreement on February 16, 2005. Of the 83 signatories to the original Protocol from 1997, the US is conspicuously absent. The only nation not to have ratified the tenets of the treaty despite having a presence at the bargaining table, the American government turned away under President George W. Bush after his election in November 2000. Citing the provisions which allowed exceptions for “major population centers such as China and India,” Bush’s administration opted out of ratifying the agreement. (The Senate had already spoken in July 1997, voting unanimously with the Byrd-Hagel Resolution against the US even signing the Protocol in the first place.) Frustrated with exclusions and a piecemeal response by more industrialized nations, the Canadian Minister of the Environment, Peter Kent, announced his country would be backing out of the treaty on December 11, 2011. “The Kyoto Protocol does not cover the world’s two largest emitters, the United States and Canada, and therefore cannot work” he said. “If anything it’s an impediment.” The day before, representatives from almost 200 countries met in Durban, South Africa and made a deal for a new agreement to replace the Protocol starting in 2015. Without strict enforcement of the provisions on a worldwide basis, the Protocol “has failed to produce any discernible real world reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases in fifteen years,” according to a 2010 paper from the London School of Economics. Among the environmental community, hope for a stronger successor to the agreement still lingers, especially after the Washington Declaration of 2007 demonstrated a mutual desire amongst industrialized and developing economies for a global cap-and-trade program. Also On This Day: 1646 – A Parliamentarian victory at the Battle of Torrington ends the first English Civil War 1918 – The Council of Lithuania declares independence 1923 – Howard Carter opens the burial chamber of Pharaoh Tutankhamun 1959 – Fidel Castro becomes the Premier of Cuba 1968 – Haleyville, Alabama activates the first 911 emergency telephone service in the United States You may also like : February 16 1923 – Howard Carter opens the burial chamber of Pharaoh Tutankhamun February 16 1959: Fidel Castro sworn-in as Prime Minister of Cuba

February 16 2005 – The Kyoto Protocol Becomes Binding

World map of countries who singed kyoto Protocol In a bid to bring the world’s industrialized nations under one umbrella to slow global warming, the Kyoto Protocol was signed by…