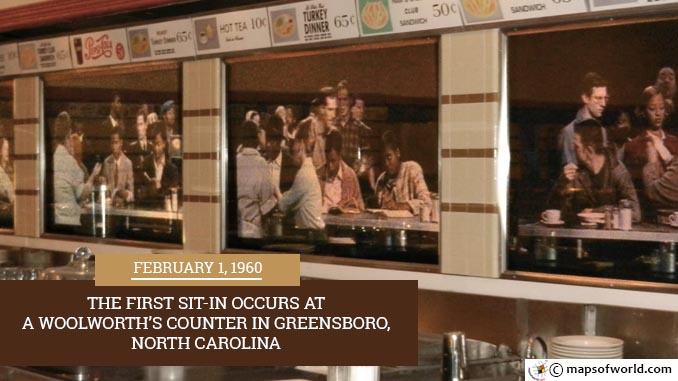

Four freshmen from the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina (NC A&T) walked into the Woolworth’s store on South Elm Street in Greensboro, sat down at the lunch counter and ordered a cup of coffee on February 1, 1960. The African-American men, fully aware they would not be served in the “whites only” restaurant, remained in their seats until closing time without receiving anything. Though not the first such protest, the sit-in launched the Civil Rights Movement onto the national stage like never before. Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond and Ezell Blair, Jr. (Jibreel Khazan after his conversion to Islam) had just started the second half of their first year in college. Like many of the students in the primarily minority population at NC A&T, they were well aware of the Jim Crow laws making segregation legal throughout the South. Word of peaceful protests like the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama and major opposition demonstrated during the integration of Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas had spread, leaving McNeil wondering how he might help to advance the cause. Though he grew up in North Carolina, McNeil’s family moved to New York shortly after he graduated high school. When he opted to attend college near his birthplace, traveling on the bus left him with a gradual demonstration of social inequality. Whereas he could eat wherever he liked in cities like Philadelphia, the transition into Maryland just 50 miles to the southwest turned him into a second-class citizen forced to search out African-American restaurants, if there were any at all. “To face this kind of experience and not challenge it meant we were part of the problem,” McNeil would later say. The strategy for the four men was simple: walk in and sit at the lunch counter for service until close. In talking through the plan, they opted for the Woolworth’s on Elm for two major reasons: 1) it was a flagship for the company, with 25,000 feet of retail space and 2) the chain allowed African-Americans to sit at the counter without an issue in New York but not North Carolina, deferring to “local custom.” On February 1, 1960, the “Greensboro Four” started by asking for a cup of coffee. Jack Moebes, a photographer from the Greensboro Record, snapped an iconic photo of the four young men at their seats and published it alongside an article about the demonstration. News spread like wildfire. The next day, journalists and TV cameras arrived — and so did another dozen or so students, not to mention several others protesting peacefully on the sidewalk across the street. Harassed by white patrons, the black protesters sat quietly and read books or studied for exams. The next day, February 3rd, all but three of the 66 seats at the lunch counter were filled by African-Americans. (The waitresses on staff, unable to work because of the policy prohibiting service, sat in the others.) Fueled by coverage on national news outlets, sit-ins were occurring throughout North Carolina and as far away as Lexington, Kentucky in a week. With a thousand people packed in and around the Greensboro Woolworth’s, only a bomb threat on February 6th could slow the demonstration down. The idea had already made inroads, though, and the city of San Antonio, Texas voted to integrate all lunch counters just six weeks after the Greensboro Four sat down. With President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower on board from mid-March, the protests increasingly took on a new angle: college students all over the country were picketing in front of Woolworth’s buildings. The deep loss of profits and negative publicity put pressure on corporate headquarters, who finally relented and instituted full integration nationwide on July 25, 1960. A major victory for groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the national spotlight created a platform for the Civil Rights Movement to become a real force for change as the 1960s wore on. Focused on the non-violent means of protest championed by Martin Luther King, Jr. and others, the media soon picked up on sit-ins and other demonstrations aimed at desegregation across the country, which helped facilitate the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Fifty years to the day after the Greensboro Four took their seats, the former Woolworth’s store that became the epicenter of the protests was reopened as the International Civil Rights Center & Museum on February 1, 2010, honoring struggles for fair treatment from all corners of the globe. Also On This Day: 1709 – Alexander Selkirk is rescued from a desert island, inspiring Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe 1884 – The first volume of the Oxford English Dictionary is published 1893 – Thomas Edison opens the first American motion picture studio in West Orange, New Jersey 1897 – Shinhan Bank, the oldest banking operation in South Korea, opens in Seoul 1942 – With the Marshalls-Gilberts Raids, the United States Navy launches its first action against the Japanese You may also like : February 1 1884 – The first fascicle of the Oxford English Dictionary is published

February 1 1960 – The First Sit-In Occurs at a Woolworth’s Counter in Greensboro, North Carolina

Four freshmen from the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina (NC A&T) walked into the Woolworth’s store on South Elm Street in Greensboro, sat down at the lunch counter…