World over water crisis takes many shapes

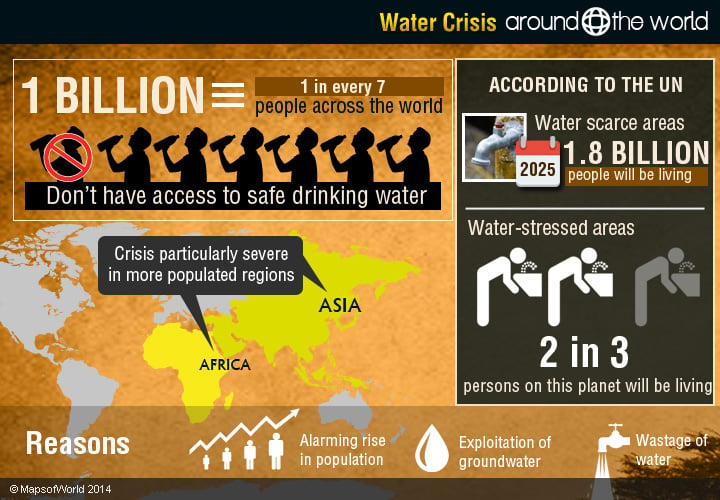

It is not a false proverb that Water is life! As without water, life will become non-existent. Around a billion people today, that is one in every seven people on earth, don’t have access to safe drinking water. According to the UN, in the past century, water use has grown at over twice the rate of population increase. By 2025, an estimated 1.8 billion people will be living in areas hit by water scarcity. And, two in every three persons on this planet will be living in regions classified as ‘water-stressed.’

The crisis is particularly severe in the more populated regions of Asia and Africa. This could have a direct bearing on regional and global security. A 2012 report, by the US intelligence community, warned that water overuse in countries like India could become a source of conflict. And, the Pacific Institute, which is into studying issues of global security and water crisis, has noted that violent confrontations over water have quadrupled in 10 years.

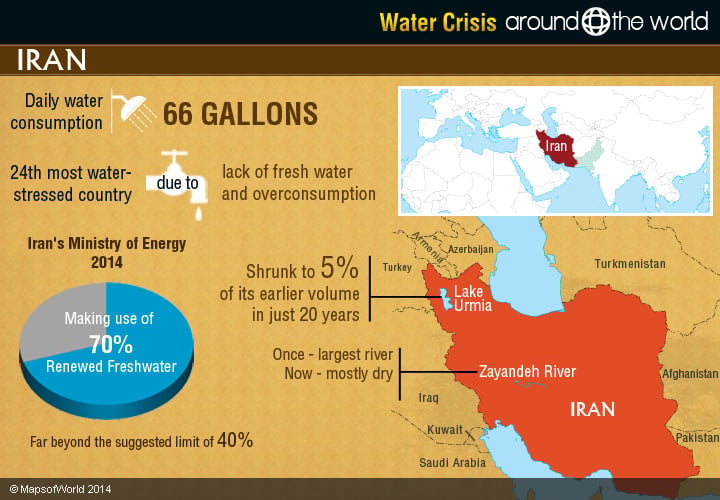

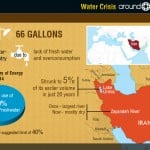

Iran

Iran faces multiple challenges as far as its water management is concerned. Iranians use 66 gallons of water daily, on an average. But lack of fresh water and overconsumption of water has made it the world’s 24th most ‘water-stressed’ country, as per the 2013 report of the World Resources Institute. As of 2014, and according to Iran’s Ministry of Energy, the country is making use of 70 percent of the total renewed freshwater, which is far beyond the suggested limit of 40 percent.

A glaring example of the water crisis is Lake Urmia, once a mighty salt lake, but now has shrunk to a shocking five percent of its earlier volume in just 20 years. The Zayandeh river, which stands for “life-giving river”, and was once the largest river that flowed through the heartland of Iran is now mostly dry after being used for several purposes.

Alarming rise in population, over exploitation of groundwater, and rampant wastage of water, especially in cities, are among the reasons for the situation of water crisis that Iran finds itself in.

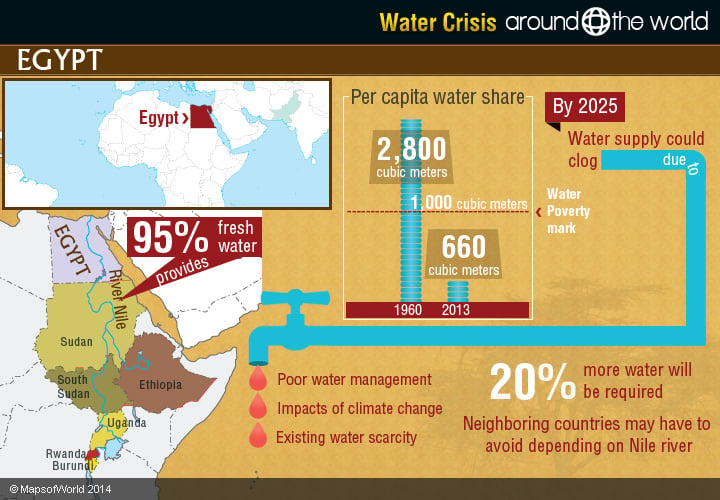

Egypt

In the 1960s, people in Egypt had a water share per capita of 2,800 cubic meters. In 2013, it stood at 660 cubic meters, significantly lower than the international standard – ‘water poverty’ mark of 1,000 cubic meters.

The future looks bleak. As the country’s current supply of water could clog by 2025 given the situations of poor water management, impacts of climate change, and already existing water scarcity. Egypt will then require 20% more water with the pressure on the mighty Nile river, which gives Egypt 95 percent of its fresh water. Unfortunately, in such a situation, Egypt’s desiccated neighbors like Burundi and Ethiopia may have to avoid depending on Nile river.

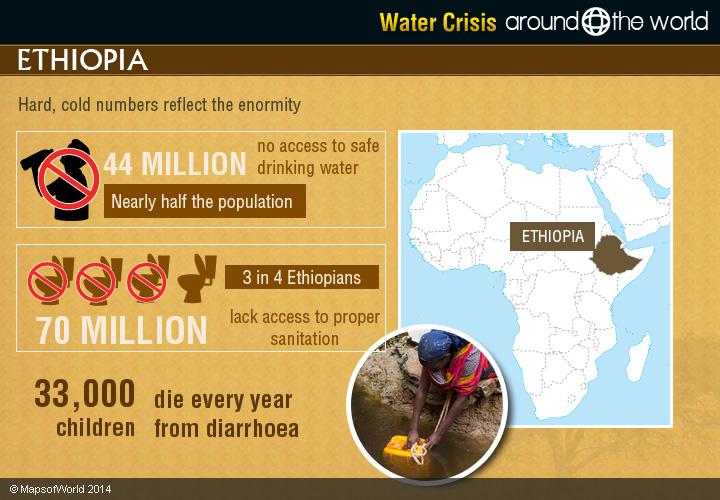

Ethiopia

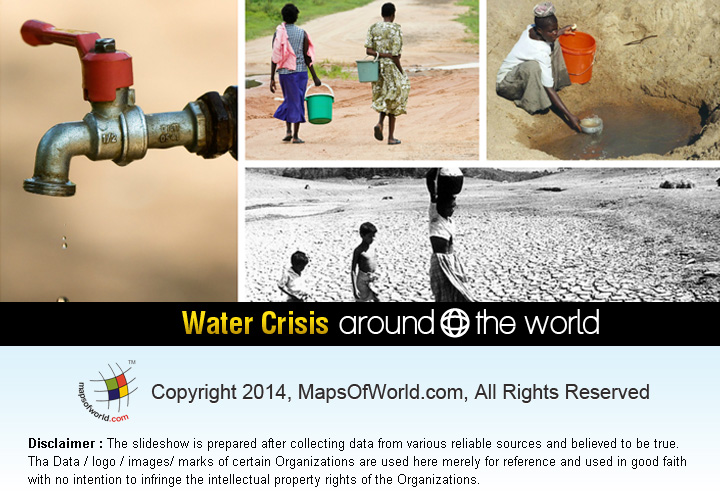

The hard, cold numbers reflect the enormity of the water crisis that Ethiopia faces. Around 44 million people — that’s nearly half of the country’s population — have no access to safe drinking water. More than 70 million — three in every four Ethiopians — lack access to proper sanitation. Unsafe water and inadequate sanitation take a huge toll on this poor African nation, with more than 33,000 children dying every year from diarrhoea.

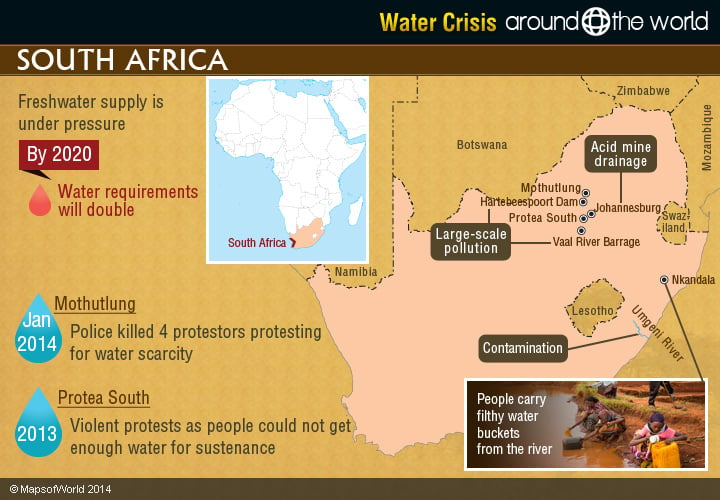

South Africa

Because of its growing population and economy, South Africa’s freshwater supply is coming under a lot of pressure. According to estimates, by 2020, the country may face serious water shortages, and its total water requirements will double in the next three decades. Current challenges to secure water resources, include acid mine drainage in Johannesburg, large-scale pollution of the Vaal River Barrage and Hartebeespoort Dam, and contamination of the Umgeni River.

However, the situation of water crisis does not end here. At several places of Africa violent confrontations, protests, dissents sparked due to water scarcity that led to the killings of innocent people. In Mothutlung, in January 2014, the north-west town of South Africa four protestors protesting for water scarcity got killed by the police. Violent protests unleashed in 2013 in Protea South as people could not get enough water for sustenance. In Nkandala, hundreds of families go without a regular supply of water. People are often seen carrying filthy water buckets from the river.

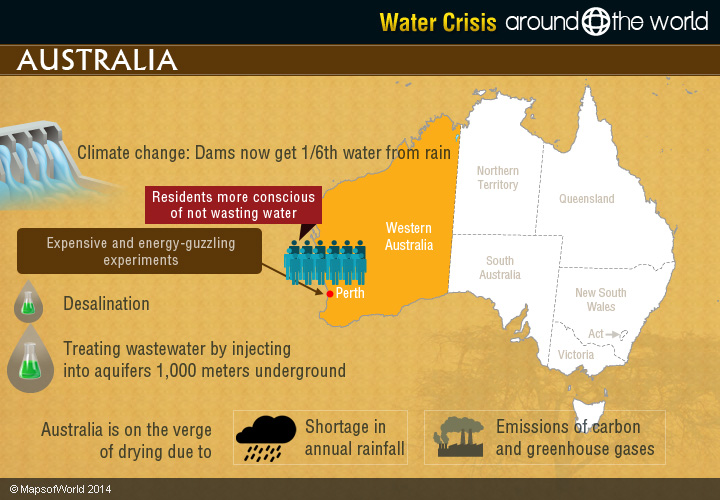

Australia

In the dry state of Western Australia, because of climate change, dams now get one-sixth of the water from rain than they used to 15 years ago. It seems like a full-blown water crisis. For the state’s capital Perth, a city of two million, the solution has been an expensive and energy-guzzling one: desalination. Another novel experiment that’s being currently implanted is treating wastewater, which is then injected into aquifers that are 1,000 meters underground. The realization that water is a scarce commodity has also made residents of Western Australia more conscious of not wasting it.

Also, according to the latest studies, Australia is on the verge of drying due to the shortage in annual rainfall and emissions of carbon and greenhouse gases. So far, the danger of facing the worse water crisis prevails over perth, as it may have to depend upon other water resources in near future.

Niger

About 8.2 million population of Niger has little access to clean water and more than 15 million people lack access to adequate sanitation. Some 12,000 children are known to die every year from diseases like diarrhoea and typhoid caused due to unclean water and poor sanitation in this West African nation. Years of internal conflicts and the situation of severe drought in 2005 that gave rise to food and water paucity have only added to the problem.

However, in the last couple of years, with levels of violence down, some steps are being taken to address the water crisis. The World Bank has initiated a program, wherein nearly 100 wells and pumps will be installed every year to meet the demands of an extra 25,000 people.

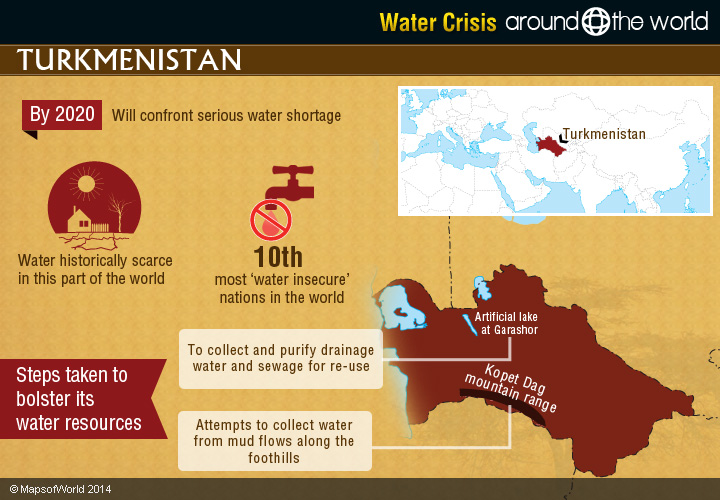

Turkmenistan

According to some experts, Turkmenistan will confront serious water shortage by 2020 unless urgent steps are taken. Water has been historically scarce in this part of the world. More than half the country is desert. One study in 2010 stated that Turkmenistan is ranked ninth among the 10 most ‘water insecure’ nations in the world.

One of the steps this central Asian nation is taking to bolster its water resources is building an artificial lake at Garashor, which will collect and purify drainage water and sewage for re-use. Attempts are also being made to collect water from mud flows along the foothills of the Kopet Dag mountain range.

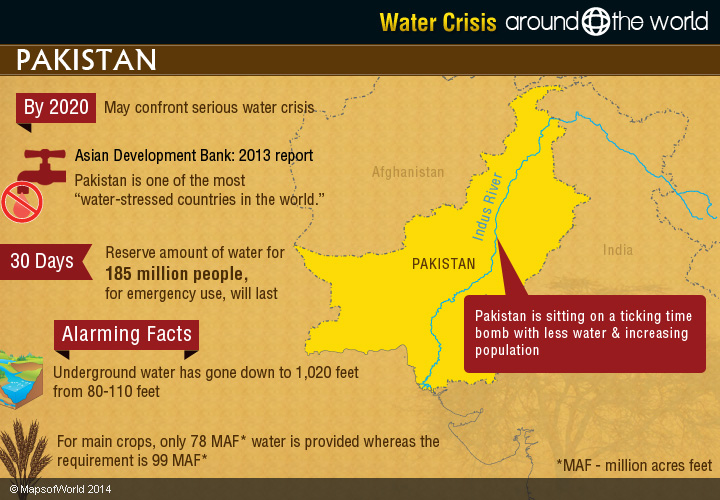

Pakistan

Militancy and ethnic violence are not the only security threats Pakistan faces. The water crisis is now on an equal footing with terrorism in this part of South Asia and it is an equally ominous development. According to a July 2013 report by the Asian Development Bank, Pakistan is one of the most “water-stressed countries in the world.” The amount of water this country of over 185 million people has on reserve for emergency use will only last 30 days. The recommended number of days for a country with similar climate is 1,000. With lesser water flowing into the Indus River and a rapidly increasing population, Pakistan is sitting on another ticking time bomb.

Here are some glaring facts on the current situation in this country: The level of underground water has gone down to 1,020 feet from 80-110 feet and is termed a worse scenario. For main crops, water requirement is 99 million acres feet (MAF), however, often only 78 MAF water is made available. Also, since partition per capita availability of water in a year has dropped drastically to about 1,500 cubic meters from 5,000 cubic meters.

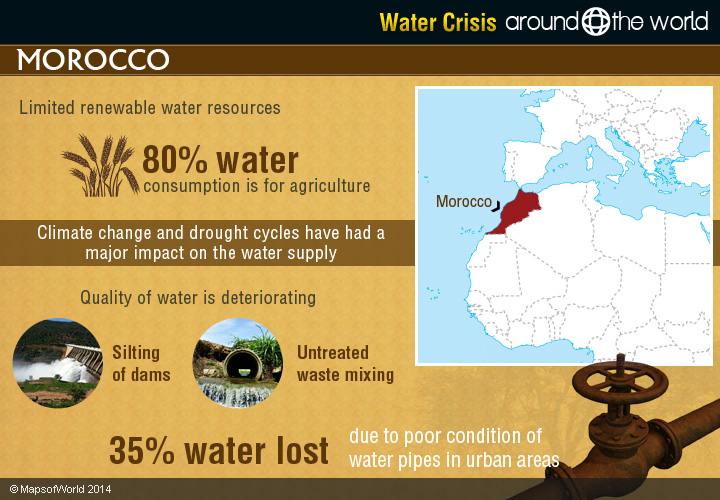

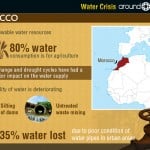

Morocco

Morocco has limited renewable water resources. Agriculture is a major activity here that accounts for 80 percent of water consumption in the country. But climate change and drought cycles have had a major impact on water supply. Besides, the quality of water is deteriorating. The reasons for this, include the silting of dams and untreated waste mixing with water.

According to estimates, 35 percent of water is lost because of the poor condition of water pipes in urban areas.

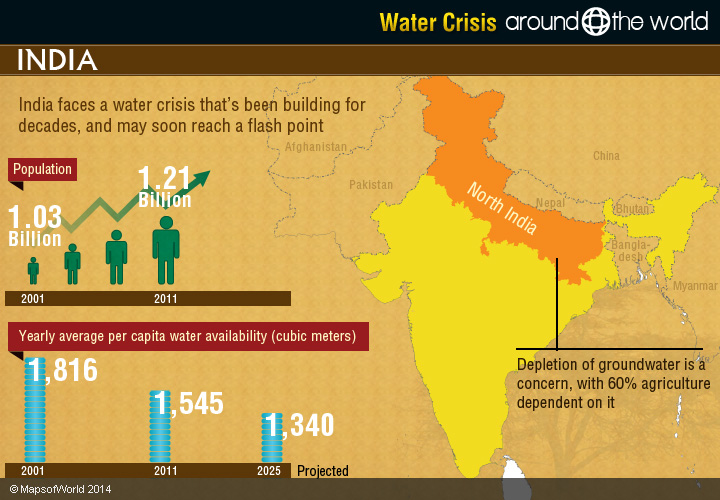

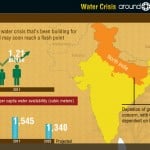

India

India faces a water crisis that’s been building for decades, and may soon reach a flash point. While India’s population increased from 1.03 billion in 2001 to 1.21 billion in 2011, the yearly average per capita availability of water went down from 1,816 cubic meters to 1,545 cubic meters in the same period. This makes India officially ‘water-stressed’ — that is, per capita availability is below 1,700 cubic meters. India’s water crisis is set to get worse: by 2025 the per capita availability is projected to be 1,340 cubic meters.

Severe depletion of groundwater is another serious concern, with 60 percent of agriculture in north India dependent on groundwater. In another two decades, according to the World Bank, India’s underground aquifers will reach a “critical condition.”

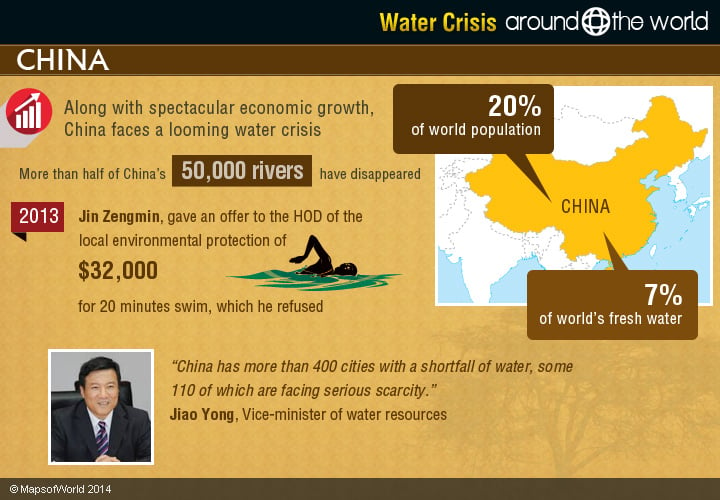

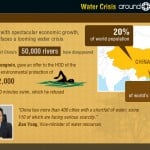

China

Along with its spectacular economic growth over the last two decades, China faces huge ecological challenges. One of them is the looming water crisis. Indeed, if India and China can get their acts together, a significant dent would be made in the global water crisis.

Incredibly, more than half of China’s 50,000 rivers that existed at the beginning of the 20th century have disappeared.

Jiao Yong, the country’s vice-minister of water resources, was quoted as saying in 2014: “China has more than 400 cities with a shortfall of water, some 110 of which are facing serious scarcity.”

More bad news: Over 70 percent of the country’s lakes and rivers are polluted — and this according to government reports — with nearly half suspected to contain water unfit for human contact or consumption.

Though China has over 20 percent of the world population, but contains only seven percent of its fresh water. In 2013, Jin Zengmin an entrepreneur of eyeglass from east China gave an offer to the head from the department of the local environmental protection on social media that went viral. He proposed to give $32,000 to the head provided he swims in the closeby river for 20 minutes, which the chief refused.

This implies that the current water situation has reached to an awful stage globally and it’s high time when nations must come together and take unified, concrete, and definitive measures to combat this critical situation.