To experience the richest variety of life, you need to visit a rainforest. And when it comes to rainforests, North America trumps every other continent in the world.

The planet’s greatest density of biomass (the total mass of organisms in a given area) is found in the temperate rainforests of Olympic National Park. The trees of the forest represent a large percentage of the equation. Indeed, the park’s huge, lichen-draped conifers are some of the biggest living things on the planet.

The cathedral forests of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, bigleaf maples, and western red cedar fill the river valleys on the west side of the main body of Olympic National Park, providing welcome habitat for the large Roosevelt elk as well as numerous black-tailed deer. The richness of these valleys boggles the imagination.

Moss coats just about every surface, and lichen drapes from nearly every limb. Trees grow to more than 250 feet tall and upward of 200 feet in circumference. These are trees that rival their famous California cousins, the redwoods and sequoias, in size and grandeur. A walk among them is an experience that will be remembered forever.

President Theodore Roosevelt protected the area as a national monument in 1909, and his distant cousin Franklin D. Roosevelt designated it as a national park 29 years later. The park gained an added level of protection and distinction late in the 20th century, when the United Nations recognized the unique nature of the park and listed it as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981; it is also recognized by UNESCO as an International Biosphere Reserve.

For all its natural beauty, majestic forests, and rugged terrain, the park area was initially protected because of its elk. Theodore Roosevelt awarded the region its national monument status most of all because he wanted to ensure the protection of a species of elk found primarily in the rainforest valleys on the west side of the park.

By 1912, the elk population on the Olympic Peninsula had dwindled to fewer than 150 animals. The protections covered by the national monument and, later, national park designations, kept hunters from taking those last few animals.

Today, elk thrive within the park, and rightfully bear the name of their protector. Roosevelt elk are the largest species of elk in North America. In Olympic National Park, they have ready access to rich and plentiful food sources.

How to Visit

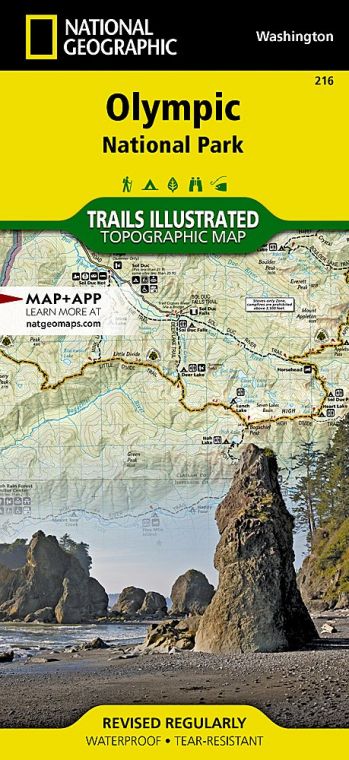

This is a big park, and all the access roads are winding two-lane highways that can slow down travel times. Plan two days for a basic visit and at least a week for a more thorough exploration of Olympic.

For an introductory park experience, head to Port Angeles and drive up to Hurricane Ridge. The 17-mile park road climbs steeply as it heads from near sea level to more than 5,000 feet in elevation.

Explore the verdant meadows and enjoy the stunning views—grand panoramas to the north encompass Canada’s Vancouver Island across the Strait of Juan de Fuca east to Mount Baker and the peaks of the North Cascades. To the south, the Olympic Mountains stretch across the horizon, highlighted by Mount Olympus and its gleaming glaciers.

After a morning spent exploring the mountains, drive west on U.S. 101 to Lake Crescent. Here you can spend the afternoon hiking one of the many trails of the area.

On day two, continue south on U.S. 101 through the logging town of Forks to the Hoh River Valley. Drive up the river road to explore the world-famous Hoh Rain Forest, where trails lead among the huge, moss-draped trees through a landscaped blanketed with ferns.

Continue south to the coastal strand of beach. Here, the park’s Kalaloch Lodge (a good option for an overnight) is close to the highway, with grand views of the wild Pacific Northwest coast. From Quinault, U.S. 101 leads to Aberdeen. Turn east on U.S. 12 to Elma, then northeast on Wash. 8 back to U.S. 101 near Olympia. Take I-5 back to Seattle.

Useful Information

How to get there

Few roads penetrate far into the massive park, but scenic highways encircle it, providing good access. U.S. 101 wraps around three sides of the park, with U.S. 12 passing the park’s southern boundary. Visitors approach via the Bainbridge Island Ferry from Seattle, or across the Tacoma Narrows Bridge from Tacoma.

When to go

The park offers great activities year-round, even winter, when Hurricane Ridge offers snowshoe routes and even a small rope-tow ski area. In the westside rainforests, it can rain at any time.

Visitor Centers

The main Olympic National Park Visitor Center, open daily, is at 3002 Mount Angeles Road in Port Angeles.

Headquarters

600 E. Park Avenue Port Angeles, WA 98362 nps.gov/olym 360-565-3130

Camping

Olympic National Park operates 13 drive-in campgrounds, first come, first served, except Kalaloch, Mora, and the group site at Sol Duc, which can be reserved at recreation.gov. Backcountry permits are available from visitor and information centers, ranger stations, and online.

Lodging

Within the Park is Kalaloch Lodge (thekalalochlodge.com; 360-962-2271). Check olympicnationalparks.com for other options, including Lake Crescent Lodge (360-928-3211), Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort (360-327-3583), Log Cabin Resort (360-928-3325), and the historic Lake Quinault Lodge (360-288- 2900), on that lake’s south shore. For a list of neighboring communities offering accommodations: nps.gov/ olym/planyourvisit/lodging.htm.

US National Parks Map

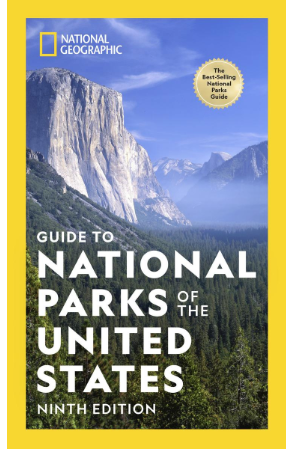

About the Guide