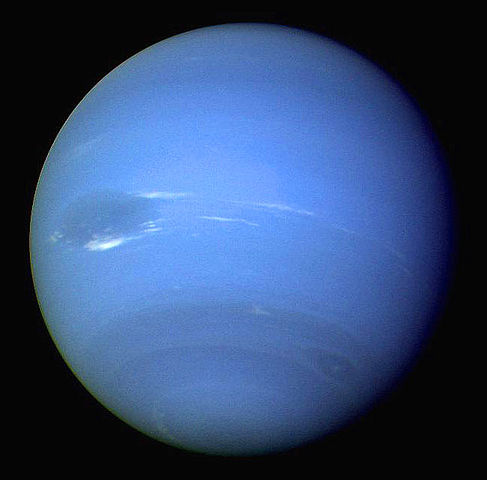

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons After first being sighted in the night sky by Galileo in 1612, it took well over two centuries for scientists to determine the bright object near Jupiter in the famous Italian’s notes was not a star. Urbain Le Verrier and Johann Gottfried Galle, working together on the European continent, and John Couch Adams, making calculations independently in England, learned the heavenly body was actually the planet Neptune on September 23, 1846. In the early 1600s, as Galileo first began to utilize the telescope to look to the heavens and describe what he observed, the lenses he had created offered too little magnification to see Neptune as much more than a small, shining blip. Fooled by the planet’s slow retrograde motion through the sky, he continued his work under the assumption it was a star. Alexis Bouvard, attempting to determine the orbits of the planets in 1821, realized the planet Uranus seemed to be swayed and theorized another large object nearby might be affecting it. Two decades later, Adams focused his energies on the same issue. Unsatisfied with the limited data he had managed to gather, he made an inquiry with the Astronomer Royal, George Airy, in search of more information to help him with his search for a new planet. Upon receiving a large number of observations in February 1844, he spent two-and-a-half years attempting to determine where this unknown celestial body might be. At the same time, Le Verrier focused his attention on determining what Bouvard had found. Unable to muster much in the way of interest, he published a series of estimates in June 1846 — figures that ended up on Airy’s desk and, when combined with the predictions Adams had made, encouraged him to make the search more of a priority. Turning the two astronomers’ work over to James Challis, director of the Cambridge Observatory, Airy hoped to find the planet quickly. Le Verrier, struggling to find scientists in his own country willing to pay attention and collaborate, wrote a letter to Galle at the Berlin Observatory detailing his findings. Arriving on the morning of September 23, 1846, Le Verrier’s note proved to be the final catalyst to the discovery of Neptune. After nightfall, Galle located the planet just one degree away from where Le Verrier had predicted it would be and 12 degrees away from Adams’ calculated location. The eighth planet in Earth’s solar system had been officially discovered. When the news went public, officials on both sides of the English Channel scrambled to make sure their astronomer got the credit. Adams would go on to claim he had mistakenly marked the planet as a star in his observations early in August due to an inaccurate map of the sky, though he was largely ignored as the scientists came to a compromise — each of the three men deserved the plaudits. Late in 1846, after names like “Janus” and “Oceanus” had been bandied about (not to mention a vain attempt by the French to have it called “Leverrier”), the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences pushed Le Verrier’s first suggestion — Neptune — to the fore. Honoring the Roman god of the sea, it remains the farthest planet from the sun. Also On This Day: 1642 – First commencement exercises at Harvard College. 1806 – The Lewis and Clark expedition returns to St. Louis from the Pacific Northwest after a three-year journey. 1821 – Some 30,000 Turks are massacred at Tripolitsa, Greece during the Greek War of Independence. 1909 – The Phantom of the Opera is published in Le Gaulois as a series. 1972 – Phillipine President Ferdinand Marcos institutes martial law.

September 23, 1846 CE – Astronomers Discover Neptune

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons After first being sighted in the night sky by Galileo in 1612, it took well over two centuries for scientists to determine the bright object near…

416