The British colonial government in India, hoping to curb the perceived increase in crime associated with nomadic tribes in northern India, passed Act XXVII — later known as the first Criminal Tribes Act in a series. On October 12, 1871, the Governor-General of India officially instituted the policy, requiring men of the suspect groups to report to police a minimum of once per week. Opposition to British rule had taken on many forms, but through the 1850s a particular cult, the Thuggee, gained a reputation for mingling with traveling nomads and killing them in order to get hold of valuables. The most famous amongst a large group of criminals loyal to little more than themselves — and known to occasionally incite an uprising — the association with other low-caste peoples allowed the British to lump the whole of them together. When the first Criminal Tribes Act came into effect on October 12, 1871, it essentially forced the suspect class to conform to British ideas of civilization. Unable to move freely across northern India, as they had for generations, people were easier to monitor — they had to show up at a set location and check in with a police officer. Newer generations were immediately guilty by association, assumed to be part of a legacy of criminal activity and, in a sense, acting out of an inherited nature because they could not help themselves. By the time the Act gained the force of law, approximately 160 groups would be required to comply. Modern societies might call this racial profiling, yet at the time it was considered a necessary reform in order to help people resist their antisocial tendencies and take on jobs which benefited the community as a whole. Much like people who are released from prison today, those who fit into the “criminal tribes” brought with them a negative stereotype that made it difficult for them secure work within the limited areas they were allowed to travel. Amendments soon followed. Initially focused primarily in the northern territories, the Act covered the entire nation by 1911. Restless and angry, people were soon attempting to protest the regulations in the limited ways they could. As each new change passed, the severity of punishment and intensity of oversight increased. The restrictions were so severe, that Jawaharlal Nehru, the eventual first Prime Minister of an independent India, voiced his disgust: “The monstrous provisions of the Criminal Tribes Act constitute a negation of civil liberty.” After India shook off the yoke of Britain in 1947, the movement to repeal gained steam. Once stricken from the books in August 1949, some 2.3 million people had gone from being regarded as nearly inhuman to having access to some of the privileges of the lower castes. Public suspicion has been difficult to break, however, with as many as 60 million people still marginalized despite some attempts to help them gain access to benefits afforded to others. Also On This Day: 1279 – Nichiren, founder of Nichiren Buddhism, inscribes the Dai Gohonzon (“Great Object of Devotion”) 1492 – Christopher Columbus lands in the Bahamas, believing he has reached India but instead discovering the New World 1810 – The city of Munich, Germany hosts the first Oktoberfest 1933 – Ownership of Alcatraz transfers from the United States Army to the Department of Justice 1984 – British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher narrowly escapes assassination when the Provisional Irish Republican Army bombs the Brighton Hotel

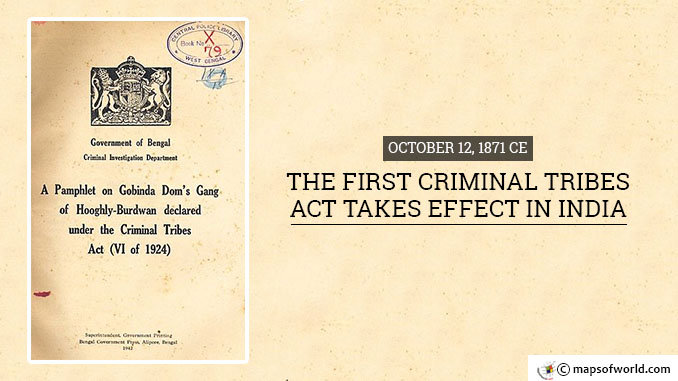

October 12 1871 CE – The First Criminal Tribes Act Takes Effect in India

The British colonial government in India, hoping to curb the perceived increase in crime associated with nomadic tribes in northern India, passed Act XXVII — later known as the first…

832