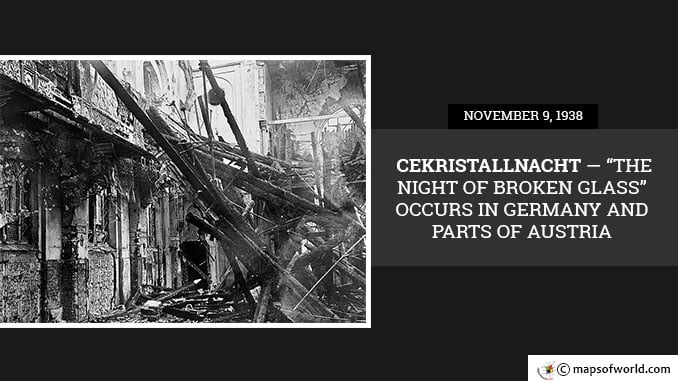

After more than five years of creating laws designed to weaken the Jewish community and spreading propaganda to raise suspicion, the Nazi leadership in Germany took advantage of an opportunity to seize on public resentment with Kristallnacht. “The Night of Broken Glass” — literally “crystal night” — on November 9, 1938 resulted in 91 deaths, the imprisonment of 30,000 Jews, wide destruction of property and the seizure of vast amounts of wealth by Nazi operatives. More than anything, the pogrom signalled a new, more aggressive stage in hostility toward the Jews, one which would lead to the Holocaust. When Adolf Hitler rose to power during the early 1930s, he moved quickly to isolate the Jewish community from the rest of German society. Making up less than 1 percent of the population, the ethnic minority would soon have the blame for the nation’s devastated post-World War I economy heaped upon them. Using a series of legislative moves, the Nazi government excluded Jews from government jobs and revoked the privileges associated with citizenship. With anti-Semitism on the rise, hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees poured into neighboring countries, prompting many nations to close borders in order to stem the tide and avoid a humanitarian crisis. By early 1938, Nazi authorities sought a means to up the ante. Looking to promote greater financial health for the lower levels of government while accelerating the Jewish exodus, officials announced in mid-summer residence permits for all foreigners — including Jews without direct German ancestry — were revoked. In late October, as part of the subsequent “Polenaktion,” some 12,000 Polish Jews were ordered to fill a single suitcase with all the belongings they could and leave for their homeland. Only a third of them were granted entry into Poland, with the rest left to languish in a refugee camp near the border, sandwiched between a country that didn’t want them and armed Nazi guards willing to kill any who attempted to retreat into Germany. With anger against the Jewish community mounting, all the movement toward Hitler’s eventual “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” needed was a spark. Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew living in Paris whose family was among those trapped near Poland, received word of what had happened. Furious, he purchased a pistol and ammunition on the morning of November 7th, then gained entrance to the German embassy and shot Ernst vom Rath, a diplomat from the Foreign Office. The 17-year-old submitted to arrest, holding a postcard in his pocket that read, “May God forgive me…I must protest so that the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do.” The killing of vom Rath — who, in a strange twist, was suspected by the government of anti-Nazi leanings — opened the door for German anger to boil over. When Hitler found out about the incident on the evening of November 9, 1938, he stormed out of an event honoring the Bier Hall Putsch, leaving Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels to utter the famous last words: “[Demonstrations] should not be prepared or organized by the party, but insofar as they erupt spontaneously, they are not to be hampered.” Within hours, regional party leaders were in the streets destroying property — joined by ordinary citizens riled up by years of anti-Jewish propaganda — with strict guidelines for stormtroopers to avoid German-owned businesses and foreign visitors. While burning synagogues and destroying the windows of Jewish storefronts, authorities were ordered to capture as many Jews as possible for deportation to concentration camps. By the end of the night, glass was strewn about the streets and some 200 houses of worship were on fire in Germany alone, with perhaps another hundred or so in the capital of annexed Austria, Vienna. According to official Nazi reports, approximately 100,000 Jews had been arrested and some 20 percent of all Jewish property was claimed by the government in the following days. Though local opinion is frequently described as mixed — some Germans cheered the destruction while others found it unseemly — other nations decried the policy as horrifying, leading many to end diplomatic relations with Germany. By the time Nazi tanks rolled into Poland in September 1939, an additional 115,000 Jews had fled to other corners of the globe. Though Kristallnacht arrived some three-and-a-half years before the official declaration of Hitler’s Final Solution, the world clearly understood German intentions for the Jewish people in the build up to World War II. Also On This Day: 1799 – Napoleon Bonaparte leads the coup d’etat against the French Directory Government 1888 – Jack the Ripper kills Mary Jane Kelly, his last confirmed victim 1918 – Kaiser Wilhelm II leaves the throne of Germany, making the country a republic after the German Revolution 1979 – The United States military detects a Soviet nuclear strike at NORAD and the Alternate National Military Command Center at 8:50am, later recognized as a false alarm 1989 – East Germany opens its borders to allow citizens to travel freely into West Germany

November 9 1938 CE – Kristallnacht — “The Night of Broken Glass” — Occurs in Germany and Parts of Austria

After more than five years of creating laws designed to weaken the Jewish community and spreading propaganda to raise suspicion, the Nazi leadership in Germany took advantage of an opportunity…

472