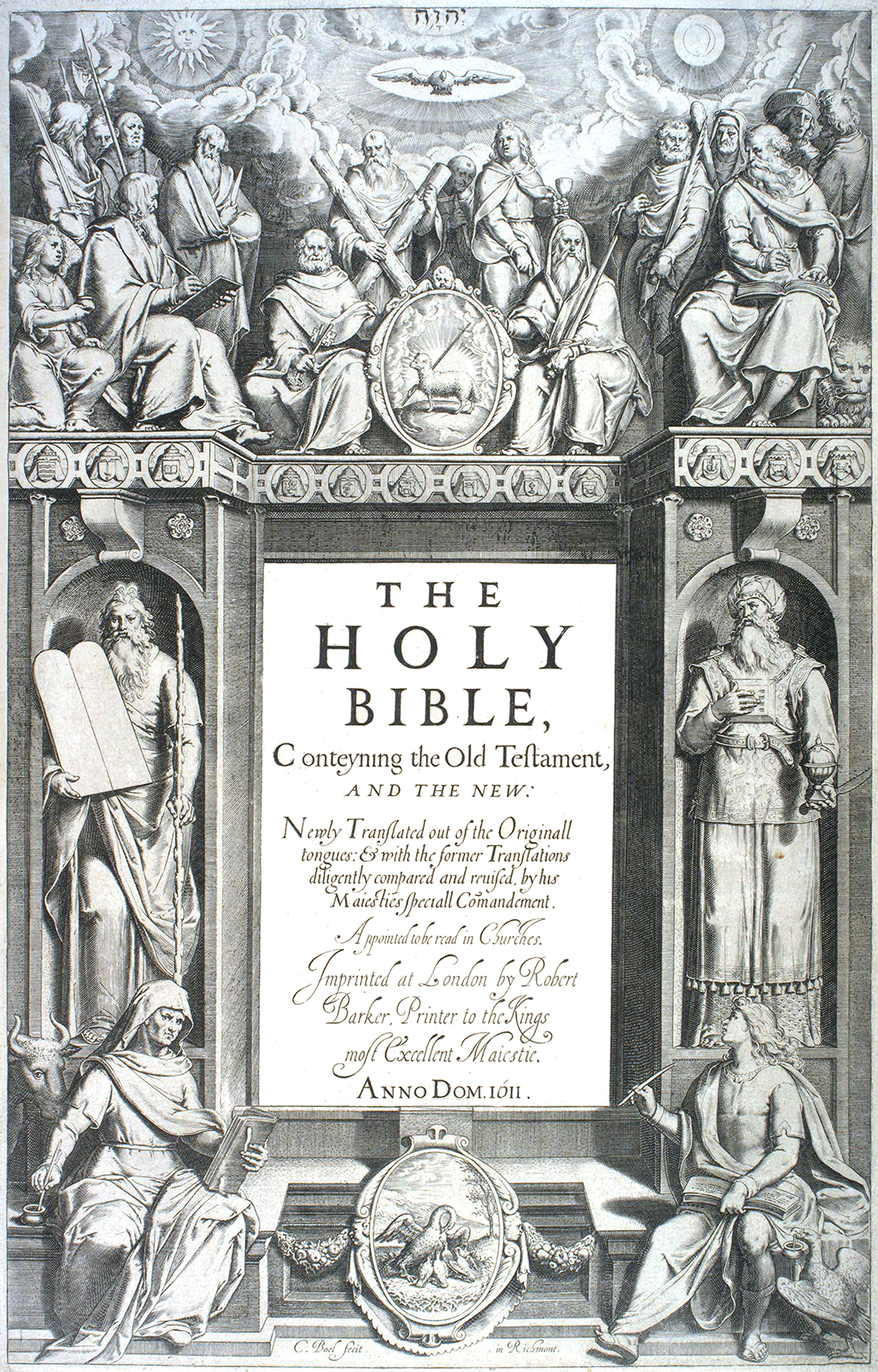

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons After seven years of hard work by 47 scholars, Robert Parker sent the King James Bible to print on May 2, 1611. In commissioning the first complete English translation of Christianity’s most sacred book, the king hoped to end protests by the Puritan faction of the Church of England. The result, beyond simply an authoritative text on which to continue building the national religion, would have far-reaching influence on the language itself. More than two centuries earlier, philosopher and theologian John Wycliffe was the first Englishman to clamor for changing the Bible from an inaccessible text in an ancient language. Greek, Latin or Hebrew were the three tongues available, depending upon whether one was reading the Old or New Testament, meaning only a few educated individuals could actually provide teaching — a boon for Roman Catholic priests and wealthy royal or noble families able to capitalize on widespread illiteracy throughout Europe. During the Middle Ages, stained-glass windows and mystery plays arose as a way for parishioners to visually identify with teaching despite being unable to read the words themselves, forcing them to rely on an educated “elect.” Though some sections of Scripture had been translated as early as the 600s, Wycliffe’s Bible represented a drastic shift. When completed in the mid-1390s, a number of handwritten copies were reproduced by his followers until the book and their beliefs were banned by the English government in 1409. Despite an active hunt by the Catholic Church to root out unauthorized translations, more than 250 manuscripts exist today, making Wycliffe’s Bible the resource most available for students of Middle English. As the Reformation blossomed after word of Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses spread throughout Europe, William Tyndale decided a fresh translation of the New Testament was in order. He spoke to the Bishop of London about the idea, yet was unmoved by the clergyman’s protest against such a willing heresy. Working from the oldest Hebrew and Greek resources, Tyndale produced a New Testament in 1526 after moving to Germany in order to avoid persecution. By the time he was caught in 1536 and killed in what is today the Netherlands, he had revised his New Testament twice and made preliminary translations of the first five books of the Old Testament — the Pentateuch — as well as Joshua, Jonah, Judges and several others. King Henry VIII of England, deeply influenced by Tyndale’s The Obedience of a Christian Man, soon called for the martyred translator’s work to be included in his official Great Bible in 1539. Over the next 60-plus years, as the Tudor line swung back and forth in the monarchy, at least three separate versions were produced by displaced religious Englishmen. In order to produce a more uniform text for the professional and layperson within his realm, James VI of Scotland listened to ideas for a fresh translation during the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in May 1601. Shortly after he took the throne of England, he brought the issue before the Hampton Court Conference in January 1604 with a mind to spread it across his entire realm. At the time, the Church of England faced a series of translation issues, according to the Puritans. Words chosen in other versions were “neither expressing the force of the word, nor the apostle’s sense, nor the situation of the place” and, in some places, altered altogether. Gathered in Hampton, representatives from the church hierarchy hashed out the particulars of a new English Bible with a group of moderate Puritans over the course of three days: no notes in the margins, special attention would be paid to traditional meanings (e.g., “church” instead of “congregation”) and, per James’ request, inclusion of support for the Church of England’s structure. In order to complete the vast undertaking — there are nearly 775,000 words in the Bible — a group of 47 scholars was divided into six committees spread across the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge and Westminster Abbey, each beginning work near the end of 1604. In a little over three years, review copies were presented for final revisions. Once the General Committee of Review completed its edits, Archbishop Richard Bancroft gave the text one last look before sending it to print, making 14 changes to better reflect his interpretation of the Church of England’s ordained status. Known officially as the Authorized Version of the Bible when it headed to Robert Barker, the King’s Printer, production of the book began in earnest on May 2, 1611. The process was expensive, forcing Barker to manufacture new typefaces and procure vast amounts of ink and paper. In addition to the time spent equipping the printing presses for the task of making the 366-sheet Bible, workers sewed together each copy, forcing a thick needle through the almost 1,500-page book. (Legal disputes between Barker and two publishers he licensed printing rights to in order to defray costs would continue for almost two decades.) In the years to come, the King James Version faced stiff competition for the role of primary teaching Bible in most churches. Due to the success and affordability of the edition produced by English expatriates in Geneva during 1560, many common folk eschewed the new translation. It took more than 60 years — and the upheaval brought on by Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell during the Commonwealth — for the “New Translation” ordered by King James to become the accepted version. Early in the 1700s, as scholarly opinion warmed to the English translation following two key revisions from the Cambridge Press that cleared up hundreds of misprints, it became clear the King James’ Bible would be at the heart of English-speaking Christianity. In 1769, Benjamin Blayney at Oxford produced a new standard text, one which has remained relatively intact for almost 250 years. With British colonial dominance spreading all over the world well into the 20th century, the King James’ Bible became the book most frequently used to convert conquered peoples both religiously and socially. Though updated translations began to appear in the late 1800s, it remains one of the most popular books available in stores to this day. According to experts, some 257 different phrases have jumped into the English language from the text of the King James Bible, including common expressions like “salt of the earth,” “the land of the living” and “apple of his eye.” For its role as a literary and linguistic landmark for the English language, the book has been called “the most influential version of the most influential book in the world.” Also On This Day: 1536 – Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII, is arrested and imprisoned for adultery, incest, treason and witchcraft. 1729 – Russian Empress Catherine the Great is born in Prussia. 1945 – Soviet soldiers raise their flag over the Reichstag, announcing the capture of Berlin. 2000 – President of the United States Bill Clinton announces information from Global Positioning Satellites (GPS) will be available to the public. 2011 – A night raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan by American special operations kills Osama bin Laden, the man suspected to be behind the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City.

May 2 1611 – The King James Bible is Published for the First Time

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons After seven years of hard work by 47 scholars, Robert Parker sent the King James Bible to print on May 2, 1611. In commissioning the first…

752