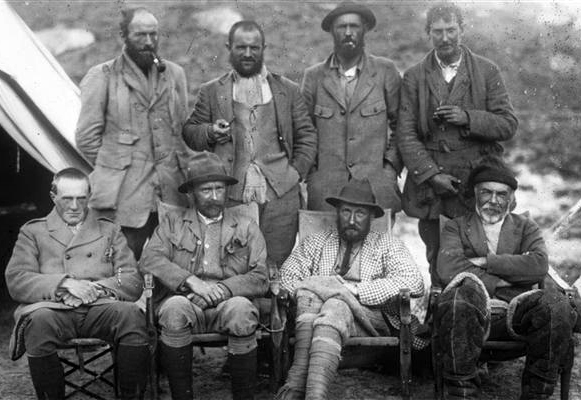

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

More than five miles above sea level, a group of four mountain climbers led by Conrad Anker found what they were looking for on May 1, 1999. A human foot jutting from the windswept rock face of Mount Everest is not often something to garner worldwide attention. Gruesome discoveries of dead climbers are common, but this one was different: it was the body of English climber George Mallory, missing since 1924. In closing the book on a 75-year-old mystery, Anker and his team deepened a decades-long debate. Mallory, an exceptionally bright student in his youth, was introduced to mountain climbing by his schoolmaster, Robert L. G. Irving, who led an annual trip as the head of a group scaling Alpine peaks in central Europe. During the 1910 edition, the party attempted to summit Mont Velan on the Swiss-Italian border, coming up short due to Mallory’s inability to adapt to the low oxygen at such heights. The following year, having experienced the physical challenges, he was much fitter. Mallory joined Irving in scaling Mont Blanc and moving along the ridge of Mont Maudit without battling altitude sickness whatsoever. Now in his mid-twenties, it became clear Mallory was hooked on the thrill of conquering a mountain. In an article published by Alpine Journal while he was fighting in World War I, Mallory summed up his attitude for tackling the challenge with a simple statement: “Have we vanquished an enemy? None but ourselves.” Returning to his life as a teacher at Charterhouse School in 1921, he immediately signed up for the British Reconnaissance Expedition bound for Everest. Much of the first quarter-century of the 1900s had been dominated by a spirit of exploration amongst European nations. With the colonial period winding down, the focus shifted toward groundbreaking contests with the worst Mother Nature offered — reaching the North and South Poles, diving deeper, flying farther, climbing higher and so on. The Reconnaissance Expedition sought to determine the best route for reaching the top of the world’s highest peak.

On September 23, 1921, Mallory and two others surpassed an altitude of 23,000 feet along the North Col, hardly more than a mile below the peak. Battered by fierce winds and worn out from mapping the region, he looked toward the summit, firmly believing the East Rongbuk Glacier could link a well-rested crew with the North-East Ridge to the top. The following year, Mallory returned as part of a team bent on conquering the mountain. Leading the third effort, Mallory and several others were caught in an avalanche on June 7, 1922 — he was the lucky one to survive, as seven Sherpas died. Two years passed before Mallory was once again at the North Col base camp, this time as climbing leader. He led the expedition’s first effort to reach the summit on June 2, 1924. He and his partner, Brigadier General Charles Bruce, pushed upward but turned back due to plummeting temperatures and severe winds. Six days later, Mallory was joined by Andrew Irvine on the third attempt, hoping to make it the 900 feet a second group fell short by on June 4th. Sometime after 12:50pm, at an altitude of more than 27,000 feet, the two disappeared from sight, never to be seen again. The last observation of the pair, made by Noel Odell from a support team trailing 1,000 feet below, placed them within three hours of the summit with exactly enough oxygen to make the trip. Conditions on the mountain worsened significantly in the hours after Mallory and Irvine were last seen, with heavy snow blanketing the summit. Despite writing an initial report claiming they had reached the so-called “Second Step” of Everest, Odell would later backtrack and state he saw them near the First. Twenty-nine years later, Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay summitted the peak on May 29, 1953, entering the record books as the first to conquer Everest. With the highest point on Earth now achieved, the mystery of Mallory’s death moved back to the forefront of the mountaineering community. In 1933, climbers discovered Irving’s ice axe along the Northeast Ridge and, some 40-plus years later in 1979, Chinese climber Wang Hong-bao related a tale of “an English dead” discovered by a Japanese team to a fellow climber before being killed by an avalanche the next day. Using Wang’s report of a body near 26,500 feet, climber Tom Holzel founded the Mt. Everest North Face Research Expedition in 1986 determined to find Mallory and Irvine. Despite the team’s effort, Mother Nature refused to cooperate — heavy snows kept the expedition from getting anywhere near the proper altitude. Lacking a concrete location to search in, it seemed as though Mallory’s and Irvine’s remains might be forever lost in the harsh climate at the high altitude. An American climber with vast experience in the Himalayas, Eric Simonson, found himself energized in 1999 by new research from Jochen Hemmleb. Combining reports of a body with painstaking studies of photographs and the location of the ice axe, Hemmleb calculated a general area in which Irving should be found. The Mallory and Irving Research Expedition, funded in part by Nova and the BBC, scheduled a trip to the forbidding mountain for spring. Within hours of setting out to scour the 56,000-square-foot search field on May 1, 1999, Conrad Anker noticed the heel of a foot approximately 100 feet from him. As he neared the location, he realized the clothing style was far different than contemporary designs, leaving him little choice but to believe the body could be Irvine. Face down and clinging to a the rock as though in the midst of a fall, the climbers identified the well-preserved corpse as that of Mallory. Suffering from a broken leg and a severe gash to the skull, the famed climber died with a handful of objects on his person: goggles, the climbing rope and, significantly, an envelope noting oxygen levels in three tanks instead of the two he and Irvine reportedly left with. The last object, coupled with the fact a picture of his wife Ruth he kept in his coat pocket was missing — carried so Mallory could place it at the summit — fueled speculation he had reached Everest’s peak before dying. The debate about the results of Mallory and Irvine’s attempt rages to this day, with most experts saying the likelihood the pair reached the summit very slim. Still, the mystery has left some to test Hemmleb’s projections to see if the Kodak camera taken along can be located, with designs on carefully developing the film if it is found. Regardless, Mallory’s legacy of a passionate pursuit of his dream has inspired countless others to attack goals of their own. His words to reporters inquiring about the necessity of the trip up Everest echo through the ages:“It is no use. There is not the slightest prospect of any gain whatsoever…What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy. And joy is, after all, the end of life. We do not live to eat and make money. We eat and make money to be able to enjoy life. That is what life means and what life is for.” Also On This Day: 1328 – The Kingdom of England recognizes an independent Kingdom of Scotland as part of the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton. 1707 – The Act of Union joins the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain. 1786 – The Marriage of Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart opens in Vienna. 1956 – Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine is made available to the public. 1961 – Fidel Castro suspends elections and declares Cuba a Socialist nation.