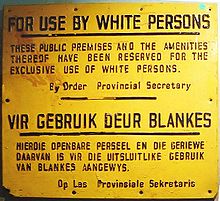

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons More than four decades after the institution of nationwide segregation, the white minority in South Africa voted to end racial discrimination against blacks on March 18, 1992. The vote, in which those in favor of abolishing apartheid outnumbered those opposed by more than two to one, signalled a historic shift in the nation at the southern tip of the continent. From the arrival of Dutch colonists in the middle 1640s, the slow creep of Europeans into South Africa represented a sea change for the native cultures of the region. By the time the British took over at the turn of the 19th century, the white settlers had enacted a series of laws to protect their own interests at the expense of tribes whose ancestry could be traced back beyond memory. In the middle of the 20th century, more than 50 years after the Franchise and Ballot Act of 1892 first limited voting rights for people of color, the progressive disfranchisement of blacks and Indians in South Africa was nearly complete. When the National Party won a slim victory in the 1948 general elections and seized control of the government, the Afrikaners — South Africans of northern European descent — were able to institute apartheid under the leadership of Daniel Francois Malan. Moving quickly, Malan’s administration pushed through new racial classifications for residents of South Africa: “native” (black), “white”, “coloured” (multi-ethnic) and “Asian.” In sweeping legislation, everything from schoolrooms to beaches was divided into areas specifically for Afrikaners and “the rest.” With the Group Areas Act of 1950, officials were able to drag families to into racially-identical neighborhoods without repercussions — segregation was not just a policy, but a strictly-enforced way of life. Almost immediately, political groups filled with non-white members protested the system. College-aged students, rallying around campuses throughout the nation, pushed the African National Congress (ANC) and other organizations to stage mass demonstrations against the white-only government. Through the 1950s, a number of steadily-expanding boycotts and strikes brought the attention of government authorities, who loosened regulations on police to allow greater use of force against the outspoken. At the dawn of the 1960s, the National Party demonstrated its willingness to neutralize resistance at any cost. Beginning on March 21, 1960, when 69 protesters were killed by police officers in the Sharpeville massacre, the cultural climate within South Africa got measurably worse from year to year. Soon, the ANC established a military arm to launch attacks on infrastructure and, by the middle of the decade, dozens of leaders — among them Nelson Mandela — were being held in prisons for no reason other than their skin color and political affiliation. Despite increasing attempts to limit movement and restrict gatherings, activists continued to find ways to speak up against unfair treatment by the white government. With the Soweto Uprising in June 1976 and murder of Black Consciousness Movement figure Steve Biko in September 1977, international pressure increased: already under economic sanctions from the United Nations since 1962, groups within Western countries were soon encouraging individuals and businesses to pull investments while demanding lawmakers apply heavier restrictions. Cut off from corporate funds and starved of trade, the South African economy was in ruins. The National Party had to make a move. President Pieter Botha quietly met with Mandela and oversaw the repeal of a handful of minor apartheid laws, possibly testing the waters for a more liberal agenda without having any real effect on the lives of South Africans. When Botha suffered a stroke early in 1989, his likely successor, Frederik de Klerk, seemed an unlikely candidate to provide sweeping change. Upon taking office in February 1990, de Klerk proved to be exactly the right man to navigate the shift away from apartheid. From his introductory address to the legislature, in which he announced the end of a three-decade prohibition against the ANC and similar groups, to Mandela’s release from prison just days later, he made it clear his administration would be a vehicle of reform for South Africa. For the next two years, the government pursued an aggressive policy of engaging anti-apartheid elements in the creation of meaningful change for the nation. At the same time, the Conservative Party and white extremists gathered steam in opposition to change. When de Klerk announced on February 20, 1992 that a national referendum on apartheid would be held, the credibility of his leadership was at stake. De Klerk put his own political career on the line: he would resign if the effort failed. The possibilities of a positive result were a toss-up at best. An increasingly unsatisfied white electorate would be the only racial group allowed to vote — a fact which gave de Klerk’s critics plenty of reason to crow. In an attempt to pacify the concerns of the ruling class, a painstaking advertising campaign enumerating plans for a democratic, racially-balanced government was laid out by the National Party and its allies. On March 18, 1992, the polls opened for the referendum to end apartheid in South Africa. At the end of the day, “yes” votes totaled a whopping 68 percent of the final tally. People the world over were stunned by the landslide, particularly when considering non-whites were barred from participation. At long last, the pathway to a government that truly represented the nation had been opened. The following day, de Klerk simply said, “Today we have closed the book on apartheid.” Negotiations to bring the government and anti-apartheid groups together continued throughout 1992 and well into 1993. Mandela and de Klerk worked diligently to ensure old prejudices would not affect the new government, earning the Nobel Peace Prize in the process. In late April 1994, South Africa held its first multi-racial elections for the presidency and parliamentary seats. Mandela won the highest office handily, collecting over 62 percent of the vote. Though economic progress would be slow, a new era for South Africa — and a generations-long process of healing from apartheid’s effects — had officially begun. Also On This Day: 1850 – American Express, then a mailing service, is founded by Henry Wells and William Fargo 1893 – Former Governor General of Canada Lord Frederick Stanley donates a silver challenge cup (later named the Stanley Cup) to determine the best hockey team in Canada 1922 – Mahatma Gandhi is sentenced to six years in prison for civil disobedience 1989 – A 4,400-year-old mummy is found near the Pyramid of Cheops in Egypt 1990 – More than $300 million worth of art is stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston

March 18 1992 – A Referendum to End Apartheid in South Africa Passes

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons More than four decades after the institution of nationwide segregation, the white minority in South Africa voted to end racial discrimination against blacks on March 18,…

383