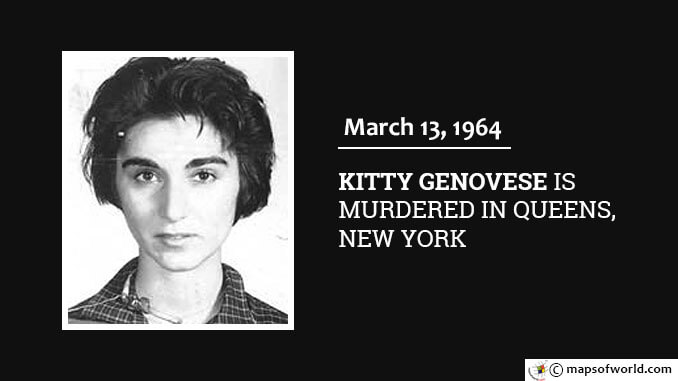

Arriving home at 3:15am was hardly a new experience for Kitty Genovese. As manager of Ev’s Eleventh Hour Sports Bar in Hollis, part of the Queens borough in New York City, late hours came with the territory. March 13, 1964 would be different: the 28-year-old woman was stabbed to death just a few feet away from her apartment building. In the investigation that followed, detectives and psychologists were exposed to the bystander effect, a peculiar quirk of human nature that kept Genovese from receiving any life-saving help.

Like most nights, Genovese parked her car in the Long Island Rail Road lot at the Austin Street and Lefferts Boulevard intersection near her Kew Gardens apartment. While crossing toward the building she lived in, Winston Moseley came up beside her. Terrified by the threatening presence, Genovese took off running, only for Moseley to catch up and stab her twice in the back. Lying on the pavement and bleeding, the young woman yelled, “Oh my God, he stabbed me! Help me!” Robert Mozer, one of the few residents in the area who reacted to the sound, stepped to his window and scared Moseley off by shouting “Let that girl alone!” As Genovese struggled to get herself to the back door of her apartment building, no one arrived to see how bad the wounds were. A few minutes later, Moseley came back to the scene in search of his prey. Tracking Genovese to the alleyway, he found her nearly dead outside a locked door. Realizing his victim was now out of sight, he proceeded to stab Genovese several more times and sexually assault her. Before he walked away at approximately 3:45am, he grabbed the cash from her purse. According to police reports, the first calls about the incident described an altercation in which Genovese was “beat up, but got up and was staggering around.” Perhaps believing the information described a minor domestic dispute, officers considered the event low priority until Karl Ross called within minutes of Moseley leaving the scene for good. Bleeding profusely, Genovese finally received treatment from emergency crews at 4:15am. Loaded into an ambulance for a race to the nearest hospital, she died on the way. Now faced with a murder investigation, detectives quickly canvassed the neighborhood for information. Person after person described hearing or seeing the attacks, but only one in each case realized Moseley had stabbed Genovese — Joseph Fink during the first and Ross in the second. Most assumed the incident was a fistfight or argument between lovers and went on about their business. Two weeks after the attack, a headline in The New York Times appeared that would bring the case national attention. Written by Martin Gansberg, “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police” was seen as a sad commentary on the increasing disconnection between people living in large cities — and maybe even society as a whole. Public outcry centered around a simple statement from an unidentified witness: “I didn’t want to get involved.” Over the next two decades, a number of writers and artists took up the case, none moreso than science-fiction author Harlan Ellison. His articles in the Los Angeles Free Press and Rolling Stone, though filled with inaccuracies, burned the issues surrounding Genovese’s death into the national consciousness. The case became part of psychology textbooks and scholarly evaluation almost instantly. It would take more than four decades for details about the circumstances of the fateful night to be clarified. A report in American Psychologist revealed in 2007 that much of the information believed by the public about the attack was false: there were around a dozen witnesses — not the 38 reported by Ellison — and none of them saw the crime in full. What was correct, however, was the tendency for large groups of human beings to shirk responsibility for providing aid to a victim. Social psychologists call this the “bystander effect,” in which individuals rationalize inaction by telling themselves others would be better suited to the task. Further, a person might justify standing still due to the lack of response by fellow members of the group. Some argue the Genovese murder and its accompanying research amount to little more than a parable, but continued study has demonstrated the effect present in a variety of situations — everything from cases of abuse to workplace theft. As a result, training programs are often put in place to help prevent future incidents, though new instances of the bystander effect occur each year, sadly. Also On This Day: 624 – Muslim forces defeat the Quraish at the Battle of Badr, solidifying the survival of Islam 1781 – William Herschel discovers Uranus 1921 – Mongolia declares independence from China 1943 – German forces clear out the Jewish ghetto in Krakow, Poland 2003 – The science journal Nature reports the discovery of footprints from an upright-walking human that are 350,000 years old