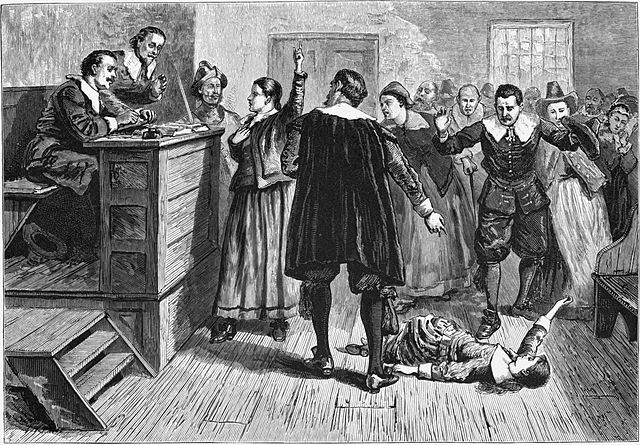

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Twelve days after two girls began to behave strangely and complain of pinpricks on their arms, Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba, a Caribbean slave woman, faced charges of witchcraft on March 1, 1692. The three women, residents of the small town of Salem Village in Massachusetts Bay Colony, were the first round of accused in an ugly chapter of New England history fueled by fears of supernatural forces and likely driven by political motivation. As Europe emerged from the Middle Ages in the late 1400s, the concept of a concerted effort by demonic forces to counteract the good being done by Christianity was widespread. Unfavorable events of any kind — poor harvests, sudden deaths, etc. — were often considered the work of Satan himself. The faithful, then, lived day by day wondering when the next assault would come. For some, to believe in the providence of God and not the schemes of his opposition was tantamount to heresy. In one generation after another, the ideas were a key feature of religious practice in many Christian sects, giving adherents reason to pray against the action of the devil’s tricksters (witches and the like) as much as for the intervention of angels, the agents of their Heavenly Father. When pilgrims from Western Europe first began to settle North America in the 1600s, the concepts crossed the Atlantic Ocean with them, taking root particularly deep in areas such as New England, where far more groups arrived after fleeing religious persecution than, say, commerce-minded settlers typically found in Virginia. The prevalence of this ideology did not, however, result in many accusations of witchcraft. Beginning in 1647, executions of suspected witches occurred only sporadically — an average of just one every four years. Massachusetts Bay was thrown into turmoil in the early 1690s, with a patchwork provincial government formed after the Glorious Revolution in England. Further, residents were under attack by Native Americans on many sides, leaving frontier villages empty as families pushed toward Boston and surrounding communities like Salem Village and neighboring Salem Town. With refugees pouring in, tensions between congregants at the local church simmered under the surface as boundaries for individual homesteads and feeding areas for livestock suddenly came into dispute. When Samuel Parris, Salem’s hardline Puritan minister, was granted ownership of the land around the church in 1689, these conflicts turned into public spectacle. Parris, eager to punish even the smallest of perceived sins, frequently required “the guilty” to repent of their ungodly behavior in front of church membership. Instead of mediating disputes between residents in private, he magnified the underlying dissension by using this policy of “accountability” to drive parties he believed in the wrong to confess with the congregation as witnesses. While this was going on, Boston preacher Cotton Mather became famous for intense descriptions of demonic activity in Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions. In it, he described a series of neck and back pains, screaming and wild, flailing movements associated with an individual suffering under the spell of a witch. When Betty Parris, young daughter of Samuel, and her cousin Abigail Williams started collapsing suddenly and making inhuman noises, the cause was clear: someone in the community had cast an evil upon them. Two more young women, Ann Putnam, Jr. and Elizabeth Hubbard, soon began to exhibit the same peculiar behavior, shouting during sermons and describing painful sensations on their skin that left no evidence behind. The local doctor was baffled, adding to the suspicion of diabolical activity. Forced to describe the reasons for this sudden change, the four girls implicated Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba in an evil scheme built on destroying Salem Village. On March 1, 1692, the three women were brought before the courts to face the allegations. Intense questioning went on for several days, ending with a confession from Tituba. Good and Osborne — outsiders in the tiny community — claimed innocence, but the damage had been done. The admission of guilt by the slave woman, likely given in the interest of self-preservation, carried with it an explosive detail: she was only one of several others working in concert with the devil. By the end of the month, another four residents were accused, including Martha Corey (who publicly asserted trouble believing the girls were telling the truth) and Good’s four-year-old daughter, Dorothy. Two months later, the courts in Salem Village were packed with “witches” all too willing to name others and avoid execution. Unsettled by the prevalence of accusations and its effects on the local court system, Governor William Phips created a special tribunal to oversee the trials. On June 2nd, Bridget Bishop became the first sentenced to death. Five more executions followed in both July and August, with eight in September. A further seven would die in jail and another, Corey’s husband Giles, was pressed to death under heavy stones for refusing to respond to charges leveled against him. When Phips dissolved the tribunal in October, 20 were dead with dozens more in prison awaiting trial. The proceedings continued until May 1693, but public interest decreased as most courts returned verdicts of not guilty. As questions about the nature of the accusations surfaced with greater frequency, Phips ordered those still behind bars released. Two years later, public opinion concerning the Salem Witch Trials began to shift. In early 1697, Justice Samuel Sewall, a member of the tribunal and by then a justice of the Massachusetts General Court, issued an apology for his role in the spectacle. Over the next 15 years, a variety of public and religious measures were undertaken to restore the reputations of those wrongly accused and executed. In December 1711, almost two decades after the first round of charges were presented, Governor Joseph Dudley created a fund to be distributed to the remaining survivors of the victims. A variety of explanations have been put forth for the incident, with everything considered from an airborne fungus causing delusions to simple human malice and jealousy. Most historians tend to place importance on social factors as the primary cause, especially divisions in the area brought on by a heated rivalry between the Putnam and Porter families and their supporters. Regardless of the motivations, there is little argument the effects of mass hysteria created an environment for false testimony and assumptions of guilt. Noticing parallels with the search for Communists run by Congressman Joe McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee in the early 1950s, Miller wrote The Crucible as an indictment against the inquiries and brought it to the stage in New York City on January 22, 1953 — burning the idea of a farcical “witch hunt” into American culture. Also On This Day: 752 BCE – The first king of Rome, Romulus, celebrates victory over the Caeninenses after the Rape of the Sabine Women 1562 – The French Wars of Religion begin with the massacre of 23 Huguenots at Wassy 1873 – The typewriter goes into mass production at the E. Remington and Sons factory in Ilion, New York 1896 – Henri Becquerel discovers radioactivity 1936 – The Hoover Dam is completed, providing electricity to Nevada, Arizona and California

March 1 1692 – The Salem Witch Trials Begin in Massachusetts

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Twelve days after two girls began to behave strangely and complain of pinpricks on their arms, Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba, a Caribbean slave woman,…

662