Two days after North Korean tanks and infantry crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea, President of the United States Harry Truman ordered the US Army to support efforts to push back the invasion. The South Korean government, led by Syngman Rhee, had evacuated Seoul on June 27, 1950 – and Truman’s directive to halt the advance of Communism would soon follow, marking the first open conflict between Western ideals and Eastern policy since the end of World War II. The battle was fierce, beginning with an artillery barrage on June 25 under the guise of a retaliatory strike by North Korea for enemy raids into its territory. Fearful of an uprising within his own country as the Communist army advanced, Rhee fled the capital, appealing to the United Nations to intervene and ruthlessly ordering the Bodo League massacre simultaneously. (On June 28, South Korean police and soldiers would begin executing Communists and their sympathizers – hundreds of thousands would be killed without trial.) For the United States, the decision to become involved came at the end of an extensive political calculation. The Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, had done little in the way of planning responses to a conflict on the Korean Peninsula. His belief, as with others in Washington, held Europe would remain the primary theater to combat the Soviet Union and a stable Japan would be the light of democracy in East Asia. After Mao Zedong formed the People’s Republic of China, making it a Communist nation, the former Pacific power remained the key in most analysts’ eyes – the Chinese and Japanese had fought two wars in recent decades, after all. To Western leaders, the assault on South Korea immediately caused fears of a diversion. With the United Nations Security Council approving the use of force, some wondered if the Union of Soviet and Socialist Republics might attempt to advance on Europe, as the US and its allies committed troops to the Asia. Just five years removed from World War II, many believed escalation into a third global conflict possible. The USSR agreed to avoid committing its own troops, easing Truman’s mind and paving the way for American air and sea forces to provide support. Despite assurances, the battle would soon create a heightened state of emergency amongst the world powers. As the US Marines and US Army entered the conflict under General Douglas MacArthur, the North Korean army would soon be pushed back to the Yalu River, giving Chairman Mao the go-ahead to commit the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army to the fight in late October 1950 – and, by extension, the involvement of Soviet arms and materiel to support the effort followed. Over the next nine months, the Chinese and North Koreans worked in tandem to inflict heavy losses on the South Koreans and Americans, pushing south of the 38th parallel once again before the US Eighth Army countered to establish “Line Kansas” just north of the previous dividing line near the end of May 1951. The next two years were largely a stalemate, with neither side gaining much in the way of territory for very long. On July 27, 1953, a cease-fire was declared and the Korean Demilitarized Zone established with little change to either country’s territorial holdings – a tragedy considering the millions killed.

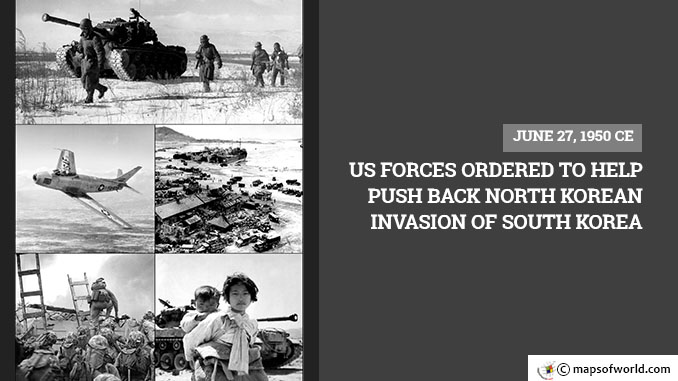

June 27, 1950 CE – US Forces Ordered to Help Push Back North Korean Invasion of South Korea

Two days after North Korean tanks and infantry crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea, President of the United States Harry Truman ordered the US Army to support efforts to…

482