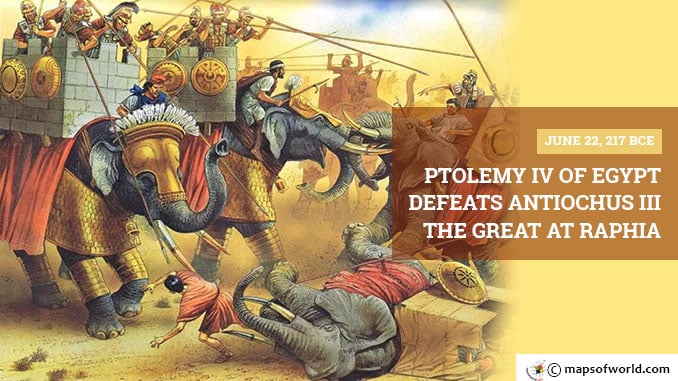

Standing on the field more than a century after the death of Alexander the Great, the descendants of the great king’s heirs were about to do battle once again. Arrayed across the plains near the modern city of Rafah in the Gaza Strip, this conflict in the Fourth Syrian War would arguably demonstrate the permanent dissolution of Alexander’s Hellenistic empire on June 22, 217 BCE. Ptolemy IV Philopator, just four years into his reign of Egypt, had taken the helm of an unstable kingdom. His court, filled with a confusing mess of silent alliances undermining authority, had an unmatched reputation for chaos – and Antiochus III, the Seleucid king determined to reclaim lands captured from Seleucus I Nicator, set out to take advantage. Antiochus launched his first raids in 219 BCE, taking Tyre and other Phoenician cities in present day Lebanon. Instead of seizing the momentum and carrying on into Egypt, he consolidated his power amongst the leaders of the new territories and allowed the Ptolemaic government to propose terms to avoid open war. Over the course of a year, Antiochus would strengthen his position such that he could raise a sizable army – Polybius later wrote more than 68,000 men would stand behind him at Raphia. The strategic issue with Antiochus’ delay was simply this: it allowed Ptolemy’s second-in-command, Sosibius, to recruit and train an army to match. More than 75,000 men gathered to meet the Seleucid assault, many of them native Egyptians – a first for the Ptolemaic war machine. Arriving on the 17th of June, Antiochus instructed his men to set up camp incredibly close to Ptolemy’s army. The proximity, roughly a half mile between them, immediately led to skirmishes and provocations. Facing the prospect of fighting the largest battle in more than eighty years, both sides hoped to tempt the other to show its cards. At night, espionage became the primary goal: Theodotus the Aetolian, a traitor who had abandoned Ptolemy for Antiochus in Phoenicia, slipped into the opposing camp to assassinate his former king. Alas, it was not to be. Ptolemy had left his tent to check the morale of his men. Theodotus retreated, knowing he would see the King of Egypt on the field the following morning. The armies rose to fight, led into the field by war elephants on both sides. The Indian variety, leading Antiochus’ forces, were much larger than their North African counterparts in Ptolemy’s army. Their distinctive scent, coupled with the imposing stature by comparison, frightened the North African elephants immediately. Terrified to see such large animals charging at them, Ptolemy’s beasts wheeled around to flea the field, trampling sections of the phalanx formed up by the men behind them. Antiochus sensed the opportunity for a quick victory. Having overpowered the left wing of Ptolemy’s cavalry, he rushed in to pursue the infantry retreating from the stampeding elephants in the center and eager to celebrate another triumph. Ptolemy’s forces gathered enough numbers to slow his advance, allowing their king and his horses to sweep in to encircle Antiochus. Unwilling to be surrounded and forced into a surrender, Antiochus turned his men back, but it was too late. Unable to regroup, his armies marched to Gaza, where he called upon Ptolemy to negotiate a truce so the dead could be buried. The impact of Ptolemy’s victory would be two-fold, he solidified the divisions between the post-Alexander kingdoms and – ironically – provided the native Egyptians with the skills and confidence to mount an uprising. Within a generation, Upper Egypt would secede from the Ptolemaic Empire, forcing conflict that – when coupled with an additional two Syrian Wars – would leave the kingdom ripe for the picking when the Romans came to the fore 150 years later.

June 22: 217 BCE – Ptolemy IV of Egypt Defeats Antiochus III the Great at Raphia

Standing on the field more than a century after the death of Alexander the Great, the descendants of the great king’s heirs were about to do battle once again. Arrayed…

399