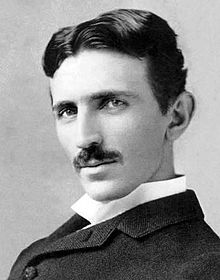

Of all the products to make their way through the labs of Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla might be the most important to modern life. Born in modern Croatia, the brilliant inventor and scientist died at a hotel in New York City on January 7, 1943. Raised in the small village of Smiljan in the Austrian Empire, Tesla’s Serbian parents were deeply involved in the local Orthodox Church — his father and maternal grandfather were both priests. By his mid-teens, the boy demonstrated a talent for mathematics, such that his instructors often believed he received the answers from someone else instead of the fast-thinking brain that allowed him to graduate in three years. Two years later, after facing down a case of cholera and evading military service in the First Balkan Crisis, Tesla enrolled at Austrian Polytechnic — known as Graz University of Technology today — and immersed himself in academic life. Working diligently (almost obsessively) to learn all he could, his professors wondered if he might burn himself out. As the strong-willed student developed opinions of his own, he clashed with his instructors more frequently, eventually losing his scholarship and leaving the school without a degree by the end of 1878. For the better part of three years, Tesla was more or less a gypsy, moving from Slovenia to Croatia to Czechoslovakia to Hungary before settling in France to work for the Continental Edison Company. Unable to attend college or find satisfying work, he had a nervous breakdown. Soon, however, his prodigious mind would meet with the job that would change his life. His eye for harnessing the power of electricity caught the attention of Charles Batchelor, who personally recommended Tesla to Thomas Edison. Now in New York City — and fulfilling a long-held dream to move to the United States — Tesla soon moved from basic work similar to what he had done in France to some of the most complex issues the Edison Machine Works faced. When he created a vast improvement on the direct current generators manufactured by the company, Tesla resigned in a dispute with Edison over bonuses. (Tesla believed he would earn $50,000 for making the changes. Edison merely provided a raise in salary from $18 per week to $28.) Determined to see his own ideas come to fruition, he started Tesla Electric Light & Manufacturing. He quickly developed a patent portfolio of his own, only to be forced out of the company by investors who believed his theories for alternating current (AC) transmission to be impossible. Though broken financially and emotionally, he managed to secure funding for a new venture months later. Untethered and brimming with energy, the inventor turned Tesla Electric Company into the testbed for his thoughts about rotating magnetic fields. By 1888, Tesla had created and patented the induction motor that would make him famous. His work eliminated the primary contention against AC and immediately put him in competition with Edison. By proving the direct current (DC) transmission promoted by his former boss was not the only way to drive a motor, Tesla rocked conventional wisdom and opened the market to a form of electricity that could reliably move over longer distances. Once he demonstrated his work for the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, he gained acclaim from many directions. Impressed with Tesla’s work, George Westinghouse approached him to license AC technology and consult with Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing for applying the motors to Pittsburgh’s streetcars. Tesla continued to work on his own ideas, possibly spurred by the peace it afforded him after arguing with Westinghouse engineers all day, far more eager soldiers than he in the “War of Currents” going on between bitter rivals Edison and Westinghouse. Three years later, with operations growing in New York, he demonstrated wireless transfer of energy from one point to another and laid the foundation for modern radio and microwave transmission. At the end of the 1890s, his impressive patent list — numbering nearly 300 when all was said and done — included a radio-controlled boat and a spark plug for gasoline engines. Facing the cramped conditions of lower Manhattan, it soon became clear he would require more space than New York City could provide. Determined to understand high-voltage electricity in depth, Tesla headed to Colorado Springs intent on opening a larger laboratory. Within months, he produced artificial lightning and redefined scientific understanding of Earth’s conductive properties, famously creating a charge strong enough to make butterflies glow and shock other residents miles away. Through the next four-plus decades until his death on January 7, 1943, Tesla became more and more reclusive. Holed up in the New Yorker Hotel, he continued to pursue projects of all kinds, theorizing the possibility of a vertical take-off and landing biplane as well as directed-energy weapons. Overshadowed — if not outright disregarded — during his own lifetime, his ideas have gained steam in recent years as proponents of fresh takes on energy consumption have become more focused on electrical cars and other “green” systems. Also On This Day: 1610 – Galileo Galilei observes four of Jupiter’s moons — Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa 1797 – The modern incarnation of the Italian flag is used for the first time 1894 – William Kennedy Dickson receives a United States patent for motion picture film 1927 – Transatlantic telephone service between New York and London begins 1999 – President of the United States Bill Clinton’s trial for impeachment hits the Senate floor You may also like : January 7 1999 – US President Bill Clinton’s Trial For Impeachment Began In The Senate

January 7 1943 – Inventor Nikola Tesla Dies in New York

Of all the products to make their way through the labs of Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla might be the most important to modern life. Born in modern Croatia, the brilliant…

332