Ten days after beginning deliberation in the most expensive murder trial in American history up to that point, jurors in the case of The State of California v. Charles Manson returned a guilty verdict on January 25, 1971. The decision against those who participated in the horrifying killings of seven Los Angeles residents would be splashed across newspapers all over the globe. Released from prison in 1967, Manson moved from southern California to the San Francisco Bay area to remake himself in a new image. Diagnosed as hostile to any sort of social norms, not to mention possessing a “tremendous drive to call attention to himself” before his most recent term behind bars, it was not long before Manson returned to his manipulative ways in San Francisco and the nearby college hamlet of Berkeley. Capitalizing on the “Summer of Love” in the Haight-Ashbury district near Golden Gate Park, he convinced a number of young men and women he was a religious teacher. Before the leaves changed colors that fall, as many as nine of his followers traveled with him up and down the West Coast in an elaborately decorated van recruiting new believers from the hippie communes they stopped in. The following spring, two of Manson’s many female followers were picked up by Beach Boy drummer Dennis Wilson. Within months the “Family” had overrun the rock star’s property, but his fast friendship with the always-convincing Manson gave the group a place to stay. Wilson introduced Manson to a handful of people in the entertainment industry, who found the former criminal an interesting personality — even a potential star as a guitarist-philosopher. Noticing the financial strain placed on Wilson, the musician’s manager forced the Manson Family to leave in August 1968. Retreating into the hills northwest of Los Angeles, the cult secured residence at the dilapidated Spahn’s Movie Ranch. During the next six months, Manson’s teachings became more volatile, focusing on the likelihood of a race war caused by angry African-Americans and his perception of the prophetic undertones of The Beatles’ White Album. In February 1969, Manson announced to his followers he finally understood what was to come: tensions between whites and blacks would result in widespread violence — a “Helter Skelter,” according to the White Album — which the Family would ride out at a hidden location in Death Valley. Once the African-American population conquered the country, Manson and four other “ruling angels” (The Beatles themselves) would take charge of the remade society. All that was left for them to do, according to his vision, would be to await the brutal crimes that would incite the larger war at their new home in the west Los Angeles suburb of Canoga Park. Impatient and restless, it seemed to Manson as though the Family would have to instigate the conflict themselves by early summer 1969. In early June, Manson shot a black drug dealer and believed he committed the first murder “necessary” to get Helter Skelter going. (The victim, Bernard Crowe, survived his wounds.) Near the end of July, three Family members killed a white man living near the Ranch in the hopes of recovering money stashed in his home and attempted to make it look like a crime from the Black Panthers, a militant African-American organization. It all came to a head during the early hours of August 9, 1969: two days after the arrest of a Family member, Manson decided the world needed a stronger push. Four of his followers drove quietly up to a home on Cielo Drive, the former residence of a Family acquaintance, brutally killing the five people inside. Sharon Tate, the young actress and very pregnant wife of director Roman Polanski, was among the victims. The White Album-inspired word “pig,” scrawled on the front door in her blood, would increase racial tension, according to Manson. The next night, another pair of Family members joined the group for two separate murders coordinated by Manson. Three descended on the home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, while the remainder headed off to a different apartment. With the LaBiancas dispatched in similarly terrifying fashion, right up to Beatles references written in blood, Manson seemed pleased. (The second team, thwarted when one Family member intentionally knocked on the wrong door, left the scene without an act of violence.) Despite the similarities, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) announced the crimes were unconnected on August 12th. The Los Angeles County Sheriff, suspecting Manson and his followers of operating a “major auto theft ring,” arrested the group on August 16th, but was forced to release them due to a typo on the warrant. While authorities slowly pieced together details during the autumn months, the Family was out in Death Valley in search of its new home, a “Bottomless Pit” described by Manson. In early December, the LAPD publicized arrest warrants for Charles Watson, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian in conjunction with the Tate murders. Within days, all three were in custody to answer for the crimes Family member Susan Atkins had been discussing with her cellmates since the Sheriff’s raid. Officials and journalists scattered all over western Los Angeles County, adding to the evidence pile when Manson and the family faced trial on June 15, 1970. A media frenzy, the trial dealt with frequent disruptions from Family members inside and outside the courthouse. Witnesses were intimidated, including the poisoning of Barbara Hoyt. Manson, despite being diagnosed as mentally unfit, insisted on representing himself during the trial and even launched himself at the presiding judge when his request to question the testimony of a prosecution witness was denied. The remaining defendants, all women, created diversions through chanting or loud noises. The jury, isolated from the world to avoid contamination by press coverage, returned a guilty verdict against all four defendants on January 25, 1971. Built largely on Kasabian’s testimony and that of other former Family members, Manson, Krenwinkel, Atkins and Van Houten jurors would recommend the death penalty three months later. Family members would go on to commit three more murders and even attempt the assassination of then-President of the United States Gerald Ford in 1975. Chief prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, writing later, detailed costs of more than $1 million and a 31,716-page compilation of testimony for the case. Saved by a California Supreme Court ruling ending the death penalty in 1972, Manson and his three co-defendants are still serving life sentences. Also On This Day: 1554 – Sao Paulo, Brazil, now the largest city in the Americas, is founded 1890 – American journalist Nellie Bly completes a round-the-world journey in 72 days 1924 – The first Winter Olympic Games opens in Chamonix, France 1945 – The Battle of the Bulge comes to an end 1971 – The ruthless General Idi Amin stages a coup to become leader of Uganda You may also like : January 25 1924 – The first Winter Olympic Games opens in Chamonix, France

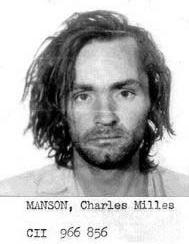

January 25 1971 – Charles Manson and His Followers are Convicted of Murder

Ten days after beginning deliberation in the most expensive murder trial in American history up to that point, jurors in the case of The State of California v. Charles Manson…

471