Of the many characters in the pantheon of American luminaries, none in the United States’ history is quite like Benjamin Franklin. Witty and curious, his wide variety of interests led to contributions in the realms of science, politics and music. Born on January 17, 1706 in Boston, he would become one of the most influential figures in the American War of Independence. One of 17 children, Franklin received little in the way of formal education. His father Josiah, a candle- and soap-maker, could only afford two years’ tuition at the Boston Latin School before funding dried up. By the age of 12, the younger Franklin was apprenticed to his older brother, James, and teaching himself through a rapid consumption of whatever books he could get his hands on. While learning the printing business in James’ Boston shop, he wrote a series of letters to his brother’s newspaper, The New-England Courant, under the alias “Mrs. Silence Dogood.” Using his pen to disguise himself as a middle-aged widow, Franklin showed the wily sense of humor he would later use to great effect in winning friends the world over. Outed by his angry brother, Franklin fled to Philadelphia the next year. Unable to latch on, he traveled to London and worked as a typesetter before returning in 1726 to serve as an assistant to a local merchant. Over the next five years, his reputation in Philadelphia society grew by leaps and bounds. He organized the Junto, a group of men focused on learning and reaching their potential, to give others the opportunity to exchange ideas. While publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette, he and several friends continued sharing books at Junto meetings, which gave Franklin the idea to create a membership base in order to finance the purchase of new reading material — the Library Company of Philadelphia was born. Through his efforts as a printer and community activist, Franklin gained wealth and status throughout Pennsylvania. Writing and reading constantly, he sold thousands of copies of Poor Richard’s Almanack for the better part of 25 years. His fascination soon spread in other directions, allowing him to invent items we take for granted today — the lightning rod and bifocal glasses being chief examples. He observed the atmosphere and ocean currents, making copious notes and testing his theories over and over again. Franklin proved his ultimate fascination would be the fullest expression of society’s capabilities. Working to organize services for the sake of the community, he created a volunteer firefighting unit to prevent wildfires in Philadelphia, manufactured anti-counterfeit currency for the neighboring state of New Jersey, co-founded the first hospital in the US and organized The Academy and College of Philadelphia, a forerunner to the University of Pennsylvania. Once he retired from business altogether in 1747, he turned his attention to politics. Now influencing the Pennsylvania Assembly, he helped to institute an unheard of level of efficiency in the postal service as joint postmaster-general for North America. (In 1775, he laid the foundation for the modern US Post Office as Postmaster General.) As the French and Indian War took hold of the colonies, he published political cartoons in the Gazette to build support for the British cause while organizing infantry and artillery units for the Continental Army. Now well-known at home and abroad in London, he argued on behalf of Pennsylvania as English policies nudged the American colonies closer and closer toward declaring independence. When he left London in March 1775, he returned just weeks after the Revolutionary War’s first combat at Lexington and Concord. At the beginning of the Second Continental Congress in 1776, he joined John Adams, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston as members of the Committee of Five working with Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence. Near the end of 1776, with the long fight to separate from Britain begun, Franklin left for France to serve as a US representative hoping to secure a treaty which would bring military support for the fledgling rebellion. Through the duration of the war, his deliberate diplomacy and delightful demeanor won him many friends in Paris. After completing negotiations to end the war with England in 1783 and negotiating an alliance with France, Franklin stayed in the French capital a further two years until returning to Philadelphia to serve as an honorary delegate for the Constitutional Convention. More than two centuries after his death in April 1790, the depth of his influence on the founding of America is unquestioned. The only man to sign the four founding documents which provided the security for the US to grow into what is known today — the Declaration of Independence, Treaty of Paris, Treaty of Alliance with France and Constitution — his writings echo a call to freedom for all that remains relevant still: “Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom, and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech, which is the right of every man.” Also On This Day: 395 – Upon the death of Emperor Theodosius I, the Roman Empire is divided for good into Eastern and Western halves 1377 – Pope Gregory XI becomes the first pope to live in Rome since Pope Clement V moved to Avignon, France 68 years earlier 1562 – The Edict of Saint-Germain recognizes the religious rights of Huguenots in France 1811 – Some 6,000 Spanish soldiers defeat a force of 100,000 Mexican rebels during the Mexican War of Independence 1966 – Palomares, Spain is the scene of a mid-air collision between an American refueling aircraft and bomber, resulting in the release of three unarmed nuclear bombs 1998 – Website The Drudge Report breaks the news of an affair between President of the United States Bill Clinton and intern Monica Lewinsky You may also like : January 17 1811 – Some 6,000 Spanish Soldiers Defeat A Force Of 100,000 Mexican Rebels During the Mexican War of Independence

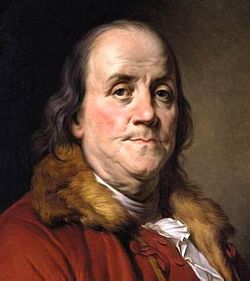

January 17 1706 – American Renaissance Man Benjamin Franklin is Born in Boston

Of the many characters in the pantheon of American luminaries, none in the United States’ history is quite like Benjamin Franklin. Witty and curious, his wide variety of interests led…

442