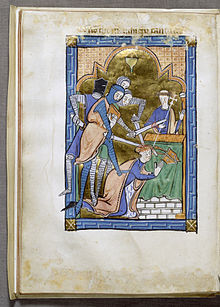

Wikimedia Commons The silence of a cold British night was broken by one of the most famous murders of the Middle Ages on December 29, 1170: four knights of King Henry II of England slipped into Canterbury Church to kill Thomas Becket, the Archbishop. After years of controversy with the monarchy over authority held by the church and state, the king had the last word. In the 12th century, much of western Europe submitted wholeheartedly to the guarantee of salvation provided by the Roman Catholic Church. Fearing hellfire and brimstone, everyone from the poorest peasant to the richest royalty looked to their local bishop for guidance. In England, the most powerful religious authority was the Archbishop of Canterbury, who often worked as a spiritual and political advisor to the king. The fact that Becket had risen to such high standing was a miracle in itself. In his mid-twenties, he secured a position as a clerk for Theobald, the Archbishop of Canterbury for then-ruler King Stephen. Despite a comparative lack of education, Becket eventually landed the official title of Archdeacon in 1154 — aged just 36 — and oversaw roughly a third of the Canterbury Diocese. Within months, he made a significant impression on the new king, Henry II, and received the title of Lord Chancellor. Becket and Henry immediately developed a close relationship, with the religious man’s measured attitude helping to soothe the king’s volatile temper. Over the years, Becket developed a reputation for astute diplomacy on behalf of the British monarchy and took on the responsibility of educating the heir to the throne. Apparently well-respected in many circles, Henry quickly moved to have Becket elevated to the Archbishopric of Canterbury when Theobald died in 1161. Overwhelmed by the magnitude of his task, Becket dove into theology with renewed vigor. Driven by deeper study and his ordination in early June 1162 — the day before he became Archbishop of Canterbury — Becket turned his focus toward defending the Church in England with all his energy. Within months, he was at odds with Henry, who likely presumed the interests of the monarchy would retain their place as chief among Becket’s thoughts when he recommended his friend for the job. By early 1164, the dispute was public. Becket, upset with Henry’s insistence on diminished protections for the clergy in the Constitution of Clarendon, turned to Pope Alexander III for help. Furious, Henry ordered Becket to appear before a royal court the following October. Unwilling to face what he believed were false charges, the Archbishop instead sought refuge across the English Channel in the court of King Louis VII. The bitter feud escalated. Becket excommunicated those in Henry’s court who had undermined his authority as head of the Church. Henry begged the Cistercian monks Becket was living with to throw him out. Though the king would make the first move toward reconciliation, offering to repeal the laws which had upset Becket, the Archbishop continued to antagonize Henry’s supporters. With Becket out of the country, Henry decided to have his son crowned as the heir apparent by the Archbishop of York in May 1170. Becket was crushed: according to tradition, he would have been the one to do so. Considering his close relationship with the junior Henry — often considered as that of a second father to the boy — the pain cut much deeper. After six years exiled in France, Becket would sail back to English shores and meet his king. Henry had one last trick up his sleeve. As Becket stepped off the ship, he did not receive his former friend as expected — the king was off seizing the possessions of the Canterbury Church. Personally insulted and seething with anger, Becket excommunicated the Archbishop of York in November 1170. This would be the final straw. When word reached Henry during his Christmas celebration at the royal vacation residence in Normandy, his rage got the best of him. He is reported to have exclaimed something to the effect of “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” William de Tracey, Reginald Fitzurse, Hugh de Morville and Richard Brito decided they could. Traveling to Canterbury, the four knights arrived sometime during the evening of December 28th and hid their weapons on Church grounds. Informing Becket he should report to Westminster to answer for his insubordination, the French warriors were immediately rebuffed. Once the king’s orders had been turned down, the four men gathered their swords and ran into the cathedral, catching up with the Archbishop of Canterbury as he headed toward the dormitories early in the morning of December 29, 1170. Slashing at Becket with their swords and injuring those who came to defend him, the knights split open the Archbishop’s head and left him to die on the floor of the monastery. When the Pope heard of Becket’s death, he immediately excommunicated the four assassins and ordered Henry not to take Mass until he made penance for his sins. Historians differ on whether or not the king meant for Becket be killed, but popular opinion at the time seems to have convicted him nonetheless. Only Henry’s promise of 200 knights for the Third Crusade would help him regain his standing with the Pope. Also On This Day: 1845 – The United States annexes the independent Republic of Texas 1930 – The Two-Nation Theory, a concept which led to the creation of Pakistan, is proposed by Sir Muhammad Iqbal 1937 – The Irish Free State adopts a new constitution, creating modern Ireland 1949 – KC2XAK of Bridgeport, Connecticut becomes the first Ultra High Frequency (UHF) television station with a daily schedule 1959 – The idea of manipulating atoms for synthetic chemistry is first proposed by physicist Richard Feynman, the inspiration for nanotechnology advances decades later

December 29 1170 – Thomas Becket is Assassinated Inside Canterbury Church by Knights Connected with King Henry II of England

Wikimedia Commons The silence of a cold British night was broken by one of the most famous murders of the Middle Ages on December 29, 1170: four knights of King…

569