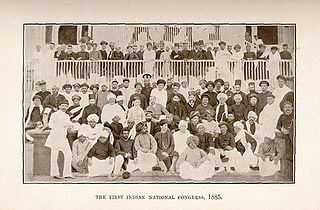

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons More than six decades before the British withdrew the colonial government, the seeds for an independent India were planted on December 28, 1885. The Indian National Congress, founded by a collection of educated elites hoping to build bridges with governors and other officials, went on to become the most influential organization in the transition to sovereignty. At the close of the First War of Indian Independence in 1857, the British government established an imperial headquarters on the subcontinent at Kolkata (“Calcutta” to the new ruling class). Over the next twenty-plus years, administrators set out to engage the natives in order to avoid the rebellions which forced the East India Company to relinquish control in the first place. Targeting those from the highest castes, the British believed they were more likely to find allies among the few who managed to secure a university education. By 1883, the responsibility for developing this coalition became the personal mission of a retired district officer named Allan Octavian Hume. Capitalizing on the simmering desire amongst Indians for independence, he composed an open letter for a carefully-chosen group of graduates from the University of Calcutta explaining they would have to “make a resolute struggle to secure greater freedom for yourselves and your country.” Appealing to citizens in Great Britain and Ireland, the first effort to raise awareness of Indian dissatisfaction with the colonial system hardly got attention on the streets of London, Manchester, Edinburgh or Dublin. The failure only served to strengthen Indian resolve. On December 28, 1885, a group of 72 delegates gathered at Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College in Mumbai to form the Indian National Congress (INC). Granted permission by the governor the previous May, the Viceroy understood Hume’s intention — coupled with that of natives like Womesh Chandra Bonnerjee and others — to be the creation of a single point of contact for the varying concerns locals might bring to the colonial government. What he got was much more than that. Natives at the head of other organizations looked upon the INC with suspicion. Considering the ties to the British administration and the large proportion of Hindus on the council, religious and cultural objections surfaced. Add the fact that only the educated had been tapped to lead the INC instead of a representative sample of the entire population — not to mention the lack of a platform for handling the widespread poverty or injustices caused by the colonial government — and it is easy to see why many were dubious as to the real purpose of the INC. By the time World War I started some 30 years later, membership slowly tilted more toward the concept of Swaraj, self-rule. Frustrated with the British prohibition against direct representation in Parliament and rightfully disgusted by the installation of an education system which ignored or denigrated Indian culture, younger INC delegates found ways to shift public opinion more towards independence. In 1916, a lawyer named Mohandas Gandhi returned from South Africa with ideas of satyagraha — non-violent protest — he had used to great effect and encouraged civil disobedience. As Gandhi’s profile grew during the period between World Wars, the INC developed a wider sense of the social ills it might be able to cure: education and sanitation issues, improving and expanding available medical care, women’s rights and more. By the late 1930s, the organization gained seats in most of British India’s provincial elections, transforming into a legitimate political party with a bubbling cauldron of ideas for transitioning India to a sovereign nation. At the close of World War II, with the British government determined to quickly divest itself of its vast and expensive-to-maintain empire, the INC and other groups stepped forward to set a new course for the country after colonialism ended in August 1947. With a Constitution and Assembly in place, it became the ruling party for three decades, suffering its first defeat in 1977. Also On This Day: 1065 – Westminster Abbey is consecrated in London 1836 – Mexico is recognized as an independent nation by Spain 1895 – The Lumiere brothers debut Boulevard des Capucines, the first motion picture shown before an audience 1895 – Wilhelm Rontgen publishes his findings of radiation he dubs “X-rays” 1912 – The City of San Francisco becomes the first municipality to purchase and operate its own streetcars

December 28 1885 – The Indian National Congress is Founded in Mumbai

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons More than six decades before the British withdrew the colonial government, the seeds for an independent India were planted on December 28, 1885. The Indian National…

365