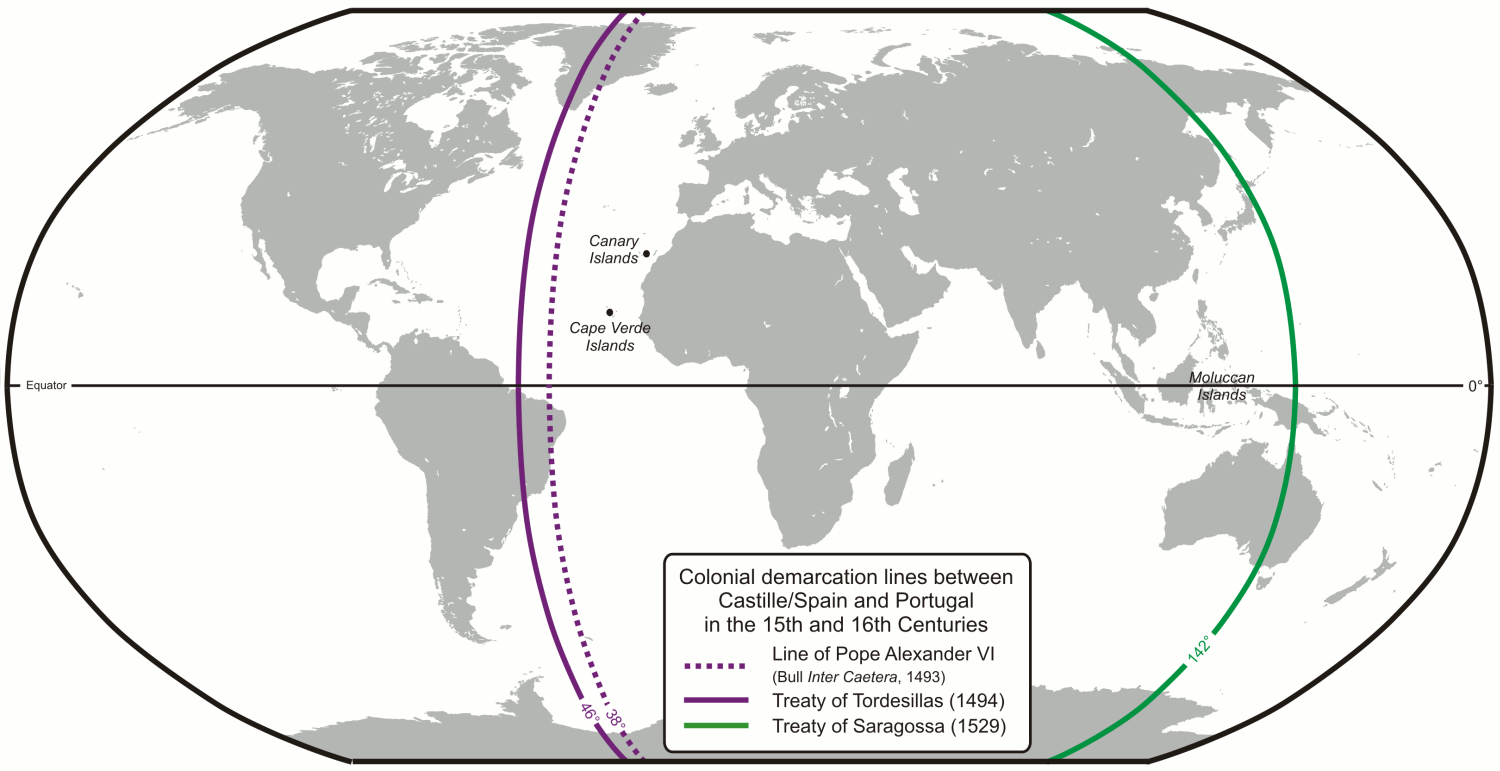

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Thirty-five years after the Treaty of Tordesillas created a boundary in the New World for Spanish and Portuguese explorers, the Treaty of Zaragoza completed the worldwide division of Iberian colonial interests on April 22, 1529. By settling a decade-long dispute over who would control the trade and settlement in eastern Asia, King John III of Portugal and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, King of Spain, created a pattern for conquering the planet outside of Europe. When Christopher Columbus reached Hispaniola in 1492 and claimed it for Spain, he inadvertently launched a race between the two naval powers on the Iberian Peninsula to grab control of vast territory in the New World. In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV granted Portugal all lands discovered south of the Canary Islands which, at that time, amounted to most of Africa and the whole of the East Indies. The Western Hemisphere provided an unforeseen problem: Columbus had landed below the declared line and planted the Spanish flag on lands unknown at the time of Sixtus’ decision. As a result, Pope Alexander VI — a Spaniard — issued a temporary division at 38 degrees west longitude in May 1493, essentially granting everything in the New World to the Spanish. By default, territories to the east would fall to Portugal, at that point made up of parts of Africa John’s men had already claimed. The Portuguese king was unsatisfied with the conditions, reaching out to the Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella to create terms more in line with his immediate aim of dominating trade in India. After extensive discussions, the two royal parties concluded negotiations with the Treaty of Tordesillas on June 7, 1494. From then on, a line between the North and South Poles along 46 degrees west would separate the two nations’ interests. Both nations immediately ramped up efforts to expand colonial holdings into the predominantly unseen areas — the Spanish launching into the Americas and the Portuguese toward Asia. By the time Pope Julius II approved of the agreement reached in Tordesillas early in 1506, both nations had already established regular sea routes well into their respective foreign claims. The rapid advance in opposite directions inevitably led to new problems: without an eastern border, the two powers were bound to clash again at the edge of the Pacific Ocean. Once Antonio de Abreu began pushing further into the “Spice Islands” in modern Indonesia, the Portuguese found themselves with exclusive trading rights to some of the most valuable agricultural resources in the world at the time. The Molucca Islands, roughly 700 miles north of Australia, were the only place nutmeg and cloves grew in 1512 — a potentially lucrative discovery. Francisco Serrao, Abreu’s vice-captain, wrote to his friend Ferdinand Magellan describing the region in detail, prompting the Spanish crown to finance a round-the-world for which journey Magellan had petitioned. On November 6, 1521, Juan Sebastian Elcano guided Magellan’s expedition into the Moluccas, giving Charles reason to claim the region as his under the regulations laid out at Tordesillas. Within a year, the colony was the subject of a military tug-of-war far from Madrid and Lisbon — an issue that would last for almost a decade. The first attempt to settle the problem came in 1524, when the Junta de Badajoz-Elvas allowed both sides to appoint three four-man teams to lay out the meridian exactly opposite the line agreed at Tordesillas three decades before. After several trips, the representatives from each side predictably designated the Moluccas as the property of the king who hired them. In the meantime, Portuguese explorers continued hopping between the islands and claiming new territory. Tensions were eased by a pair of marriages between the royal families in 1525 and 1526, giving Charles reason to find an amicable settlement so he could focus on battles erupting throughout Europe due to the Protestant Reformation. There was also the threat posed by the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Finally, on April 22, 1529, the two parties signed the Treaty of Zaragoza and proclaimed a boundary near 142 degrees east longitude, solidifying Portugal’s claim to the Indian Ocean and all of Asia while recognizing Spain’s dominion over the Americas and most of the Pacific. In reality, the division was far from equal. Portuguese lands amounted to some 191 degrees of the globe, yet Charles opted not to dispute the claim due to John’s financial support of his campaigns on the continent. Further, expeditions from both countries would establish colonies in opposing territory: the Spanish in the Philippines in 1565 and the Portuguese expanding existing holdings in what is today Brazil. Due to these incursions, the question of local sovereignty was not completely settled until the First Treaty of San Ildefonso in October 1777. Also On This Day: 1724 – German philosopher Immanuel Kant is born. 1889 – Oklahoma City and Guthrie, Oklahoma are cities of 10,000 within hours of the 1889 Land Run in Oklahoma Territory. 1915 – Chlorine gas is released at the Second Battle of Ypres, intensifying chemical weapons use in World War I. 1954 – Witnesses begin testifying about Communism in the Army-McCarthy Hearings, part of America’s “Red Scare”. 1970 – Earth Day is celebrated for the first time.

April 22 1529 – The Treaty of Zaragoza Divides the World Between Spain and Portugal for Good

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Thirty-five years after the Treaty of Tordesillas created a boundary in the New World for Spanish and Portuguese explorers, the Treaty of Zaragoza completed the worldwide…

1.4K