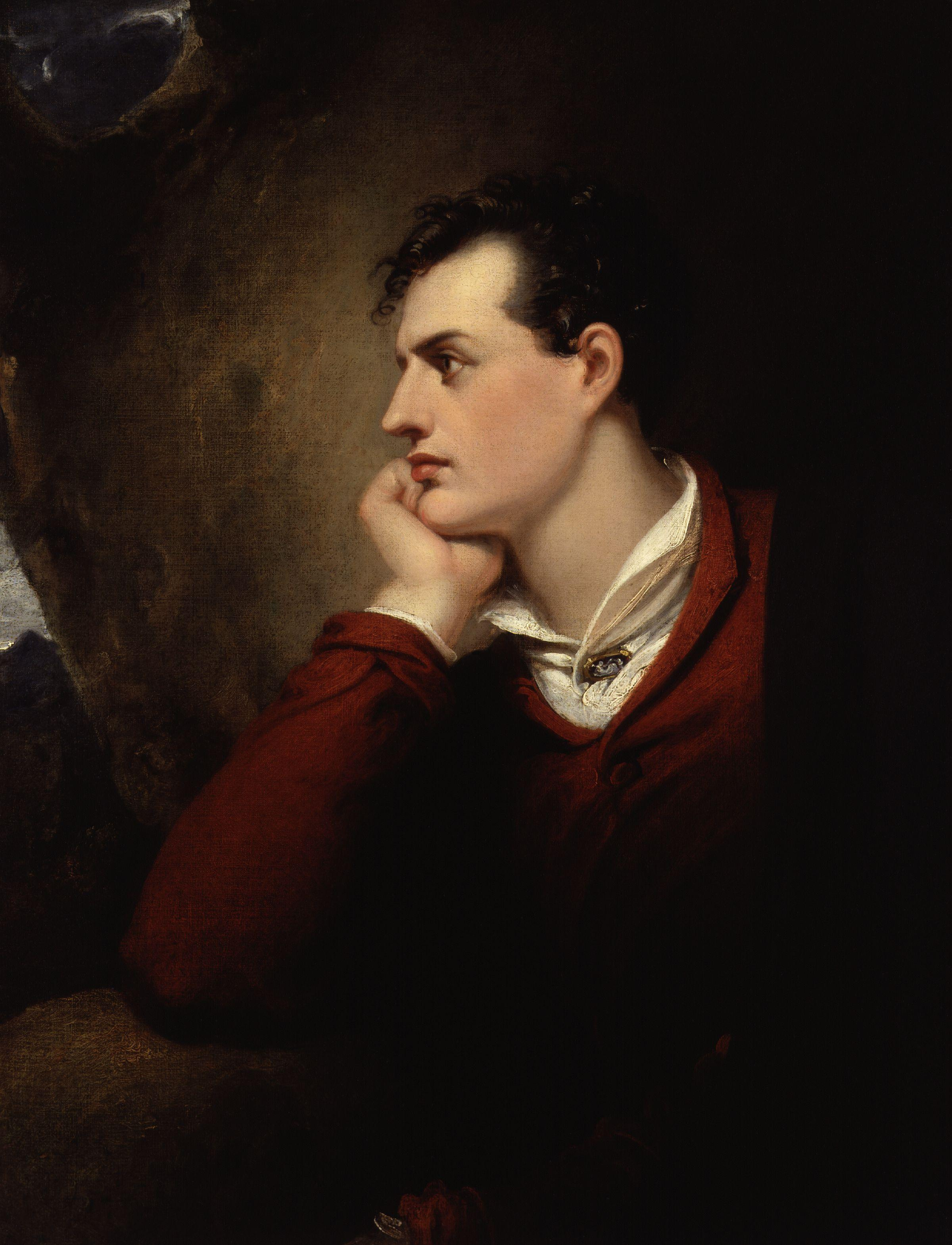

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Throughout the history of British literature, there are a litany of world-renowned authors of poetry and prose. On April 19, 1824, George Gordon Byron – famously called Lord Byron – joined the ranks of those artists who have tragically died young when he succumbed to a fever while off fighting in the Greek War of Independence. At once revered as a hero and prolific lover, Byron’s legacy continues to make a splash with each new generation. Of all the families into which a future poet could be born, it might be said Byron hit the jackpot. His mother’s family, descended from King James I of Scotland, were of the wealthy Gordon clan – the reason Byron’s father, the Royal Navy Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron, pursued his mother Catherine in the first place. Having already seduced a married woman to nab his first wife, John moved on with Catherine shortly after being widowed. With a reputation for being particularly abusive (verbally and physically), not to mention his tendency to build up extravagant debts, John put the family under pressure immediately. Catherine sold off much of her estate to pay his creditors and the two moved to France with John’s surviving daughter, Augusta, where Catherine became pregnant. Near the end of 1787, she moved back to England to ensure Byron would be born an Englishman, settling in London and welcoming the baby boy on January 22, 1788. No longer able to afford a place of her own, Catherine took Byron back to her grandfather’s estate in Aberdeenshire, Scotland during 1790. His father joined them eventually, though it appears out of a desire to borrow more money from his wife instead of a wish to strengthen the family. Frustrated and overwhelmed by financial difficulty, Catherine drank heavily. Byron, for his part, suffered from a minor physical deformity: his right foot, paralyzed or malformed from birth, forced him to work hard to hide a limp and endure painful treatments while growing up. His biographer, Scottish writer John Galt, would later write “it was scarcely at all perceptible” but Byron remained fiercely focused on keeping others from noticing even the slightest difference for the rest of his life. In 1798, Byron’s great-uncle William – “the Wicked Lord” Byron – died and passed the family estate down. Catherine, pleased at the possibility of seeing her son inherit a more manageable fortune, attempted to move to the Byron home at Newstead Abbey in central England. When she arrived, the disgusting conditions left her feeling as though the expansive house was beneath her son. She rented the home out, using it for an income to support her and Byron. To those who surrounded him as he proceeded toward adulthood, Byron seemed a perplexing mix of good-natured friendliness and erratic anger. Spoiled by his mother, the two had a combative relationship defined by a mutual stubbornness. This opinionatedness remained a staple of Byron’s personality – many referred to his seeming arrogance and disregard for others’ thoughts as a façade for his fragile emotional state. (Modern psychology might have diagnosed both Byron and his mother as victims of a bipolar disorder.) While pursuing his education during his teens, Byron gained a reputation for being quick to fall deeply in love. And, with his boyish good looks and athletic build, he had no shortage of willing recipients for his affection. The fact that he was already a published poet by the age of 14 and – like his father – prone to spending vast amounts of money made him even more interesting. Though an average and often indifferent student, his grasp for crafting verses filled with emotion proved he could produce inspired work whenever he set his mind to it. Hours of Idleness, published in 1807, officially launched his career (his previous book had been burned due to racy content) and drew the first round of criticism. He replied with English Bards and Scotch Reviewers two years later, displaying an artful knack for parody. In time, a biting poem in response to a review would become a badge of honor for a critic. After completing his education, Byron aimed to begin exploring the world. He took off in 1809, spending much of the next two years in the Mediterranean while the rest of Europe fought against Napoleon. Byron began in Portugal, before skirting along the southern coast of Spain on his way to Malta and Greece. By the middle of 1810, he had slipped into the Ottoman Empire (modern Turkey) and visited Constantinople. Writing as he traversed the seas, Byron released Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage in 1812. Public reception for the poem was overwhelming, such that “I awoke one morning and found myself famous.” The long and winding verses enthralled readers, setting him up for further success when his “Oriental Tales” — The Giaour, The Bride of Abydos, The Corsair and Lara were published the following year. During the course of scarcely two years, Byron had arguably become the best-known English poet of his era. The acclaim opened new doors for the 26-year-old Byron: he was now fêted nearly everywhere he went, a fact he used to seduce a number of women in the British aristocracy. Lady Caroline Lamb, one of his first and most public liaisons, called him “mad, bad and dangerous to know” before he broke through her protests to make her his own. He did settle down briefly, marrying Anne Isabella Milbanke in January 1815 and conceiving a daughter with her before she left him a year later, but generally moved from one fleshly pursuit to the next. Tired of life in England – and, perhaps, frustrated with unseemly rumors being spread by his ex-wife and Lady Caroline – Byron left on a Rhine River cruise during the summer of 1816. Settling on Lake Geneva in Switzerland, he got to know fellow poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his future wife Mary. During the “incessant rain,” the three joined John William Polidori, Byron’s physician, and Claire Clairmont, Mary’s stepsister and Byron’s former lover, in telling a number of outlandish stories to pass the time. The results have become well known: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Polidori’s The Vampyre. Months later, Byron moved on to Italy, first settling in Venice and then transitioning to Rome in early 1817. He continued publishing poems and seducing married women, famously composing Manfred and Cain while pursuing Marianna Segati and the Countess Guiccioli. In 1819, he chose to make Ravenna home for two years, once again motivated more by the passions of his heart (the Countess lived there) than any particular desire to settle into a new city. Eventually, Byron moved to the coastal town of Genoa, where he lived with Guiccioli until he left for Greece in 1823. A fan of the water, he commissioned his own yacht and entertained a number of guests, including the Earl of Blessington and his wife, Marguerite, who would later write Conversations with Lord Byron. Despite enjoying the company, Byron eventually became restless again and accepted an invitation to join the Greek battle for independence, providing financial support to outfit the rebel ships. Working alongside Alexandros Mavrokordatos in Missolonghi, the poet helped plan an assault on Lepanto from his station in western Greece before contracting an illness in mid-February 1824. For the next two months, Byron underwent a series of bloodlettings – a common medical practice at the time – in the belief he would be better able to overcome the infection. After a brief recovery, his fever worsened dramatically, and he died on April 19, 1824. Shocked by the sudden nature of his passing, Greeks and Britons mourned the poet deeply. During the decades after his death, Byron came to be regarded as one of the founding writers of the Romantic movement in England. His epic poems, particularly Don Juan, challenged social norms of the time and evoked both great admiration and furious scorn. When combined with his flagrant disregard for discretion when it came to relationships, Byron was somewhat marginalized by the Victorian establishment. Proclaimed during his life as possibly the best in the world by some, he remains widely celebrated throughout the world today, particularly in continental Europe. Also On This Day: 1770 – Captain James Cook sees the east coast of Australia on the horizon. 1782 – The Dutch Republic becomes the first country to recognize the United States as an independent government. 1960 – Pro-democracy protests force Syngman Rhee to resign his position as President of South Korea. 1971 – Charles Manson is sentenced to death for his role in the Tate/LaBianca murders. 1995 – The Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City is bombed, the largest case of terrorism on American soil until the attacks of September 11, 2001.

April 19 1824 – English Romantic Poet Lord Byron Dies

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Throughout the history of British literature, there are a litany of world-renowned authors of poetry and prose. On April 19, 1824, George Gordon Byron – famously…

554