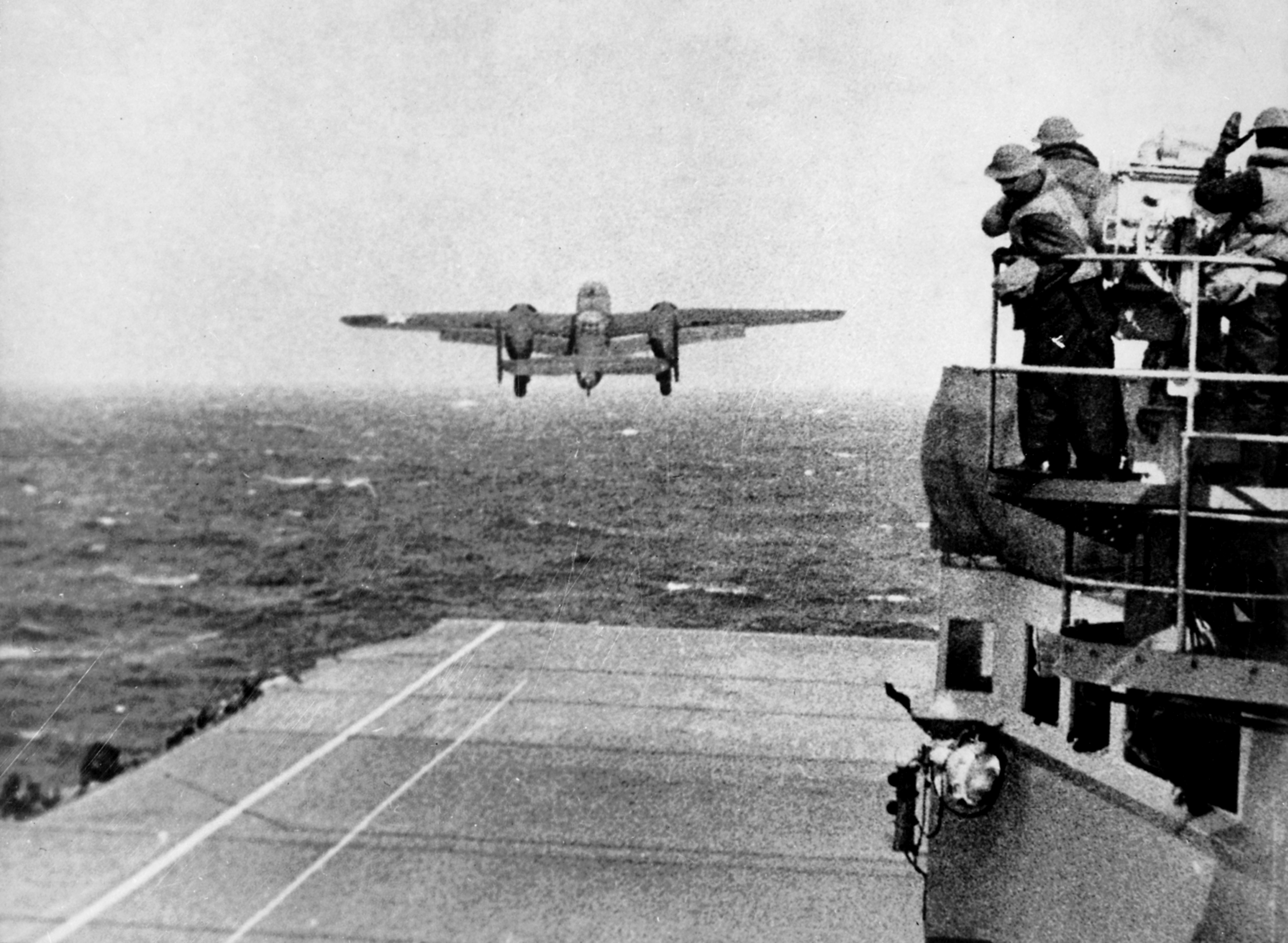

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States needed a morale boost. Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle and his crew of pilots from the US Army Air Force provided just that with a strike on the heart of Japan on April 18, 1942. The audacious raid — launched from an aircraft carrier with land-based bombers — proved to be a tremendous psychological victory despite causing limited damage. Two weeks after the Imperial Japanese Navy surprised American forces stationed on Hawaii at Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Despite a relative lack of military capability — the US had only begun gearing up for the possibility of entry into World War II months before — the President instructed his commanders to plan a raid on the Japanese mainland. The only parameter, so far as Roosevelt was concerned, was that it happen as soon as possible. Considering the logistical challenges, pulling together such a mission would require immense creativity. Following the meeting, members from every branch of service were tasked with devising a workable scheme that maximized damage and limited risks to American pilots. Captain Francis Low, a Navy Assistant Chief of Staff, returned to the office of Admiral Ernest J. King on January 10, 1942 — just 20 days after Roosevelt issued the order — convinced a lightweight Army bomber could take off from the deck of an aircraft carrier. According to Low, the runway at the base in nearby Norfolk, Virginia had a large outline painted on the pavement to help new pilots practice approaches and landings. If a plane had the proper dimensions to fit on the deck of a ship like the USS Hornet without damaging any of the surface structure, he reasoned, why couldn’t it take off regardless of the branch of the military for which it was intended? The Joint Chiefs turned to Doolittle, a well-respected aeronautical engineer and famous pilot, to flesh out details for the attack. Looking at the specifications of aircraft carriers in the American inventory at the time, he opted for the brand-new B-25 Mitchell, a twin-engine bomber with a 2,400-mile range and a shorter wingspan than other airframes in its class. After a test flight by two B-25s from the deck of the Hornet on February 3rd, Doolittle’s raid was fast-tracked. Within days, the 17th Bomb Group — the only division in the entire US military equipped with B-25s — transferred from Oregon to South Carolina. In a hangar at Lexington County Army Air Base in Columbia, the crews were asked to volunteer for a secret mission, one so classified they would not be aware of the target until absolutely necessary. Twenty-four teams chose to participate. For the next two weeks, the B-25s were moved to a secluded maintenance center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. While under heavy guard, a group of technicians modified the aircraft to increase fuel supply and remove defensive weapons — gun turrets on the belly and in the tail — in order to reduce weight. From March 1, 1942, the flight crews were put through an intense training regimen to ensure they would be able to manage the tricky process for lifting off the Hornet with a 2,000-pound munitions payload. On top of that, the pilots and navigators would have to become experts in low-level flying at night and maintaining course while skimming above the water. When the teams arrived at Naval Air Station Alameda in California at the end of the month, Doolittle believed them ready. On April 1, 1942, the aircraft were lifted onto the deck of the Hornet using massive cranes at Alameda, each loaded with four 500-pound bombs designed and manufactured expressly for the raid. With the B-25s tied down on the deck, the 17th Bomber Group’s 200-man crew boarded the ship and took up quarters below deck. At 10:00 am on the following day, the carrier was underway and bound for a rendezvous with the USS Enterprise and Task Force 16 in the Pacific Ocean. Now out on the open water, Doolittle gathered his men and briefed them on the targets: Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Nagoya, Kobe and Osaka. He then described how the B-25s would make a late-evening takeoff approximately 400 nautical miles from Japan and proceed on a nighttime bombing run over these manufacturing centers before landing at airfields in allied China. After 16 long days at sea, the planned date for the raid finally arrived. Shortly after sunrise on April 18, 1942, a small Japanese picket boat made visual contact with the Hornet and Enterprise. Though nearby escort ships fired on and sank the No. 23 Nitto Maru in a matter of minutes, the tiny reconnaissance craft managed to send a warning back to Japan. Doolittle and his men were 250 nautical miles short of the agreed launching point and had lost the element of surprise. Conferring with Captain Marc Mitscher, the commanding officer of the Hornet, he chose to put his men in the air 10 hours earlier than intended. At 8:20am, the first aircraft left the deck. An hour later, all 16 of the B-25s were bound for Japan having taken off without incident. Even with a complete lack of experience performing the risky maneuver over open water, the 17th Bomber Group took off flawlessly. For the next six hours, the raiders moved along in pairs or clusters of four until shifting into a single-file column and dropping close to the water in preparation for the attack. Right around the noon hour, Doolittle’s mission arrived over its targets facing minimal anti-aircraft fire and only a handful of enemy fighter planes. Just one of the bombers released its munitions early, forced into evasive maneuvers after its gun turret malfunctioned before it entered the drop zone — the rest were successful. As the B-25s pulled away from the southern tip of Japan, the focus shifted to a search for beacons meant to guide them in to a Chinese airfield at Zhuzhou from the East China Sea. The entire group was low on fuel, with Captain Edward J. York’s so depleted he had to turn toward the Soviet Union instead of joining the rest of Doolittle’s men. Battling the darkness and worsening conditions, the 15 planes bound for China had to be ditched along the coast. All 75 men parachuted out of their aircraft, floating down into Chinese farm country hoping they would not fall into Japanese-occupied regions. For the most part, the raiders were spirited away by helpful natives and returned to the US Navy in a matter of days. In Vladivostok, at the far eastern end of Soviet territory, York and his crew were immediately taken prisoner. Fearing the worst, Doolittle assumed he would face a court martial when he finally arrived home — the loss of 16 aircraft and untold numbers of airmen, not to mention the minimal amount of damage inflicted on the Japanese, would reflect poorly on him. Little did he know, the raid would have far-reaching strategic consequences and be one of the most celebrated in US history. Embarrassed by the Americans’ ability to penetrate Japanese airspace and threaten the Home Islands, as well as the fact the Hornet and Enterprise went undetected, Imperial commanders canceled a planned naval assault in the Indian Ocean. The pullback led to an Imperial Navy attack on Midway Island two months later, one that would set the tone for the remainder of World War II in the Pacific Ocean. Also On This Day: 1775 – Shortly before the American War of Independence, Paul Revere takes his legendary ride through the Massachusetts Bay countryside to warn of the British arrival by sea. 1881 – American outlaw Billy the Kid escapes from the Lincoln County jail in Mesilla, New Mexico. 1906 – More than 80 per cent San Francisco is destroyed by an earthquake and fire. 1909 – Joan of Arc is beatified by the Roman Catholic Church. 1955 – Albert Einstein dies in Princeton, New Jersey.

April 18 1942 – The Doolittle Raid is Launched from the USS Hornet

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States needed a morale boost. Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle and his crew of pilots from the…

461