Why India Opted for Bifurcation of its State Jammu and Kashmir?

Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) is a state that lies in the northern most part of India. On the north, it is bordered by Afghanistan and China, on the east by China, on the south by the states of Himachal Pradesh and Punjab in India, and on the west by the North-West Frontier Province and the Punjab Province of Pakistan. J&K covers an area of 222,236 sq. km (85,805 sq. mi).

The state comprises three regions: the plains in the foothills of Jammu; the blue lakes and valleys of Kashmir rising to alpine passes, and the plains and beautiful mountains of Ladakh at the high altitudes which lie beyond those passes. The Indus river flows through Kashmir and the Jhelum river rises in the northeastern portion of the territory.

While Srinagar functions as J&K’s summer capital, Jammu is the winter capital. The area is a big tourist draw due to its pristine climate and scenic landscapes.

History of Jammu and Kashmir

The state of Jammu and Kashmir which had earlier been under Hindu rulers and Muslim Sultans became part of the Mughal Empire under Akbar. After a period of Afghan rule from 1756, it was annexed to the Sikh kingdom of Punjab in 1819. In 1846, Ranjit Singh handed over the territory of Jammu to Maharaja Gulab Singh. After the decisive battle of Sabroon in 1846, Kashmir also was handed over to Maharaja Gulab Singh under the Treaty of Amritsar.

In the immediate aftermath of India’s independence on August 15, 1947, three rulers had still not merged their territories with India despite Home Minister Vallabhbhai Patel’s untiring efforts. The trio included the Nawab of Junagadh, the Nizam of Hyderabad, and Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir. The accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India was to become one of the most significant events in the politics and history of the subcontinent.

The jubilation of independence was marked by violence surrounding the partition of India and Pakistan. The founder of Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, seemed to have assumed that Kashmir, by the logic of its majority Muslim population, would become a part of his country. Hari Singh, in the weeks after August 15, 1947, was not inclined to give up his State’s independence. Pakistan then decided to force the issue, and a tribal invasion ensued to drive out the Maharaja.

In the words of C. B. Duke, the then British High Commissioner in Lahore, “[Kashmir] has always been regarded as a land flowing with milk and honey, and if to the temptation to loot [by the tribesmen] is added the merit of assisting oppressed Muslims, the attractions will be nigh irresistible.”

In the early hours of October 24, 1947, the invasion began, as thousands of tribal Pathans swept into Kashmir. Their target was the state’s capital, Srinagar, from where Hari Singh ruled. The Maharaja appealed to India for help. This prompted VP Menon, a bureaucrat considered to be close to Patel, to go to Srinagar to get Hari Singh’s nod for Kashmir’s accession to India. On October 26, Hari Singh and his officials shifted to Jammu, to the safety of the Maharaja’s winter palace, and out of harm’s way from the invading Pakistan tribesmen.

With the state facing an armed attack from Pakistan, Maharaja Hari Singh acceded to India on October 26, 1947 by signing the Instrument of Accession. Hari Singh’s prime minister, M. C. Mahajan, later recalled: “I requested immediate military aid on any terms. [I urged Nehru to] give us the military force we need. Take the accession and give whatever power you (India) desire to the popular party. The [Indian] army must fly to save Srinagar [. . .] or else I will go to Lahore and negotiate terms with Mr. Jinnah.”

Following Hari Singh’s accession, India’s 1st Sikh battalion flew into Srinagar on October 27. Srinagar was soon secured from the Pakistani invaders but the battles in the larger region had just begun.

Needless to say, when Jinnah learnt of the Indian troops’ landing, he reportedly ordered his acting British commander-in-chief General Sir Douglas Gracey to move two brigades into Kashmir — one from Rawalpindi and another from Sialkot. The Sialkot army was supposed to march to Jammu and arrest Hari Singh. The Rawalpindi column would take Srinagar. Gracey refused, arguing instead that he could not follow orders that would plunge India and Pakistan into war, without the approval of Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck. Predictably enough, Auchinleck would not agree to sending troops to Kashmir, either.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, India’s viceroy, later described a volatile meeting he had with Jinnah in the days following Kashmir’s accession to India: “Jinnah said that this accession was the end of a long intrigue and that it had been brought about by violence. I countered this by saying that I entirely agreed that the accession had been brought about by violence; I knew the Maharaja was most anxious to remain independent, and, nothing but the terror or violence could have made him accede to either Dominion; [. . .] the violence had come from tribes for whom Pakistan was responsible [. . .]”

By the time Pakistan finally sent troops to Kashmir, Indian forces had taken control of nearly two thirds of the state. Gilgit and Baltistan territories were secured by Pakistani troops. Fighting between Indian troops, and the tribesmen and Pakistani troops continued for more than a year after the accession, in what is generally known as the first India-Pakistan war.

Finally, the United Nations (UN) arranged a ceasefire at the end of 1948. After long negotiations, the cease-fire was agreed to by both countries, and came into effect. The terms of the cease-fire, laid out in a United Nations resolution of August 13, 1948, were adopted by the UN on January 5, 1949.

Since then, India and Pakistan have voiced divergent views on the Instrument of Accession and the circumstances under which it was executed. The Indian government’s stated position is: “The Accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to India, signed by the Maharaja [erstwhile ruler of the State] on October 26, 1947, was completely valid under the Government of India Act [1935] and international law and was total and irrevocable. The Accession was also supported by the largest political party in the State, the National Conference. In the Indian Independence Act, there was no provision for any conditional accession.”

Background of Kashmir Conflict

Hence, these different views on Kashmir have given rise to a long-running conflict between India and Pakistan. It’s a disputed land which is divided between India and Pakistan which started right after partition in 1947. And China is also involved in the conflict as it holds approximately 15 per cent of the land. India occupies approximately 55 per cent of the land, whereas Pakistan holds approximately 30 per cent of the land. In the last two decades, the state of J&K has been torn by militancy and separatism, leading to loss of life, property, opportunities and employment. By scrapping these contentious and outdated provisions, India hopes to bring normalcy in the region and promote national integration.

Administrative Divisions of J&K state

Until August 5, 2019, Jammu and Kashmir was divided into three divisions -Jammu, Kashmir Valley and Ladakh. These are further divided into 22 districts. They are Anantnag, Badgam, Bandipora, Baramulla, Doda, Ganderbal, Jammu, Kargil, Kathua, Kishtwar, Kupwara, Kulgam, Leh, Poonch, Pulwama, Rajauri, Ramban, Reasi, Samba, Shopian, Srinagar and Udhampur. The state had two municipal corporations, 9 municipal councils and 21 municipal boards.

Scrapping of Article 370

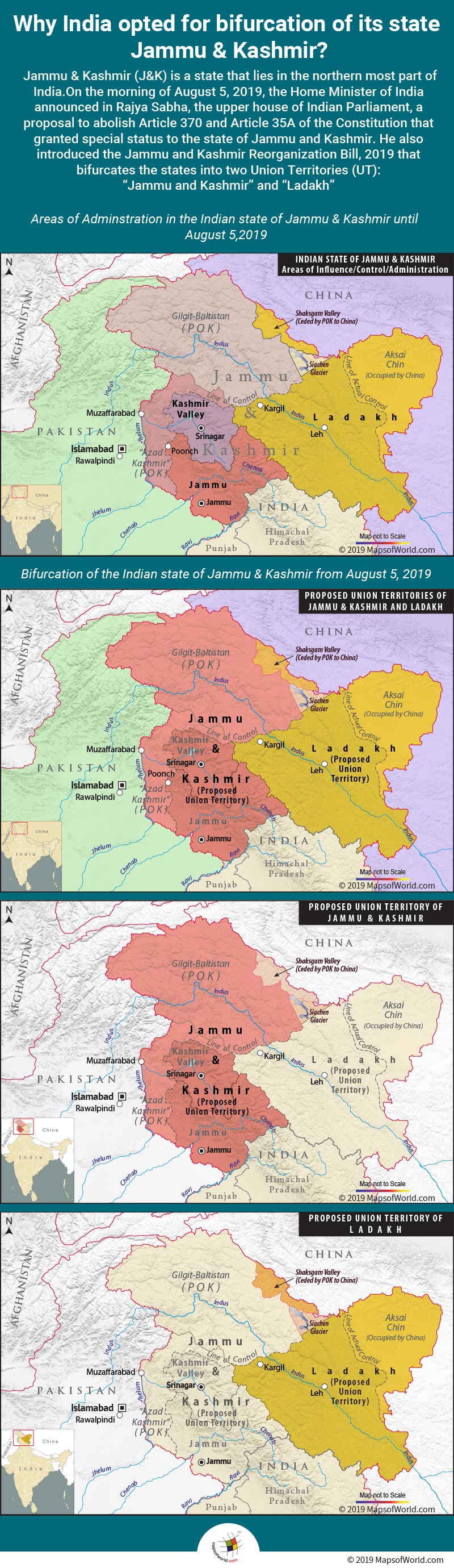

On the morning of August 5, 2019, the Home Minister of India announced in Rajya Sabha, the upper house of Indian Parliament, a proposal to abolish Article 370 and Article 35A of the Constitution that granted special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. He also introduced the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Bill, 2019 that bifurcates the states into two Union Territories (UT): Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

The UT of Jammu and Kashmir will have a legislature like the UTs of Delhi and Puducherry, while the UT of Ladakh will not have a legislature, like the UT of Chandigarh.

State vs UT: Key Differences

The most important differences between a state and an UT in India are following:

-

A State has its own elected legislative assembly and government, while a UT is ruled directly by the Central Government.

-

In a State, power is divided between the State and Central Government, while in an UT, power is vested in the Central Government.

-

A State is administered by the Chief Minister, while an UT is administered by a person appointed by the President of India.

-

The Constitutional head of a State is the Governor, while the Constitutional head of an UT is the President of India.

Till August 5, 2019, India had 29 States and 7 UTs, which included Delhi, Puducherry, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep. The number of UTs will now increase to 9, while the number of States will reduce to 28.

UT of Jammu and Kashmir (Proposed)

The Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir will constitute:

1. Jammu Division

2. Kashmir Division

3. So called Azad Kashmir (POK)

4. Gilgit and Baltistan (POK)

5. Shaksgam Valley (Under illegal Chinese Occupation)

UT of Ladakh (Proposed)

The Union Territory of Ladakh will constitute:

1. Leh

2. Kargil

3. Aksai Chin (Under Illegal Chinese Control)