Sprawled across the Continental Divide, Glacier has two sides. The west reflects a Pacific Northwest maritime climate, with abundant moisture, big narrow lakes, and lush forest. On the drier east side, where mountains stand like fortress walls above the great plains, the landscape is more open; lodgepole pine, grassy meadows, and aspen trees are common. The Going-to-the-Sun Road cuts a spectacular transect over Logan Pass, going from one side of Glacier to the other.

When the Rockies lifted up about 75 million years ago, a giant slab broke loose and slid toward the east—an event called the Lewis Overthrust. That grand block is the mountainous core of the park.

There are glaciers to be seen, but possibly not for long—they are shrinking. When they will completely disappear, however, depends on how and when we act (see p. 291). Yet Glacier was named not so much for living ice as for the tracks of it, the work of Ice Age glaciers over the last two million years. Moraines, hanging valleys, arêtes, cirques, and tarns—this is a perfect place to see these glacial landforms.

And the creatures that call this place home? Bighorn sheep, mountain goats, elk, grizzly bears, wolves, and eagles flourish here.

How to Visit

Allow plenty of time, a full day if you can, for the 50-mile Going-to-the-Sun Road, considered by many to be one of the world’s most spectacular highways. Ride the free shuttle to avoid fighting traffic and searching for a place to park. Get off at one stop, hike a distance, then get back on at another.

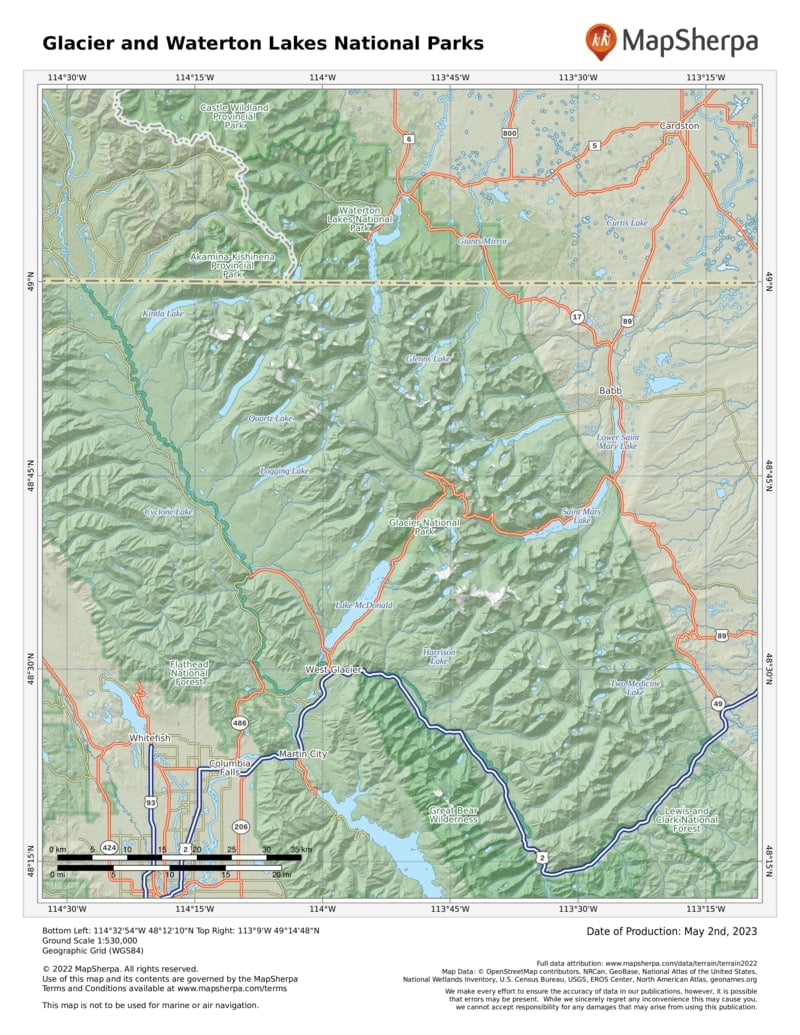

On a second day (with your passport!), travel the Chief Mountain International Highway north to Waterton Lakes National Park, in Canada, to enjoy the contrast of peak and prairie. This sister park was linked to Glacier in 1932 as a symbol of peace and friendship.

With more time, sample one or both sides of Glacier. West-side highlights include Lake McDonald, water-sculpted McDonald Creek, and ancient forests of hemlock and red cedar. On the east side, don’t miss Many Glacier, with stunning scenery and the park’s most popular trails. To the north, Waterton Lakes offers more mountain majesty with fewer visitors.

Want to get even more off the beaten path? Go north from Apgar to remote Kintla and Bowman Lakes, or south from St. Mary to Cut Bank and Two Medicine Lake. You can also take a wilderness trip, on horseback or foot. Check with the visitor center or park website (nps.gov/glac/planyourvisit/guidedtours.htm) for more information.

Useful Information

How to get there

U.S. 89 connects to east-side Many Glacier and St. Mary. U.S. 2 cuts around the south end of the park and is the main approach from the west.

When to go

June through Sept. is best. Access to the park is reduced in early spring and late fall due to weather. Many of the roads within the park are closed in winter; Logan Pass is usually not clear until mid-June. Chief Mountain Highway is open early May–Sept.

Visitor Centers

Glacier’s three visitor centers (at Apgar, St. Mary, and Logan Pass) have varying schedules but are generally open May to mid-Sept.

Headquarters

Glacier National Park P.O. Box 128 West Glacier, MT 59936 nps.gov/glac 406-888-7800

Camping

Most of Glacier’s 13 campgrounds open late May or early June. Reservations available for limited sites at St. Mary and Fish Creek (recreation.gov).

Lodging

Xanterra (glaciernationalparklodges .com; 855-733-4522) runs five hotels, including Many Glacier and Lake McDonald; lodging is also available from Glacier Park Inc. (glacierparkinc .com, 406-892-2525). For backcountry lodges contact Belton Chalets (granite parkchalet.com, 888-345-2649).