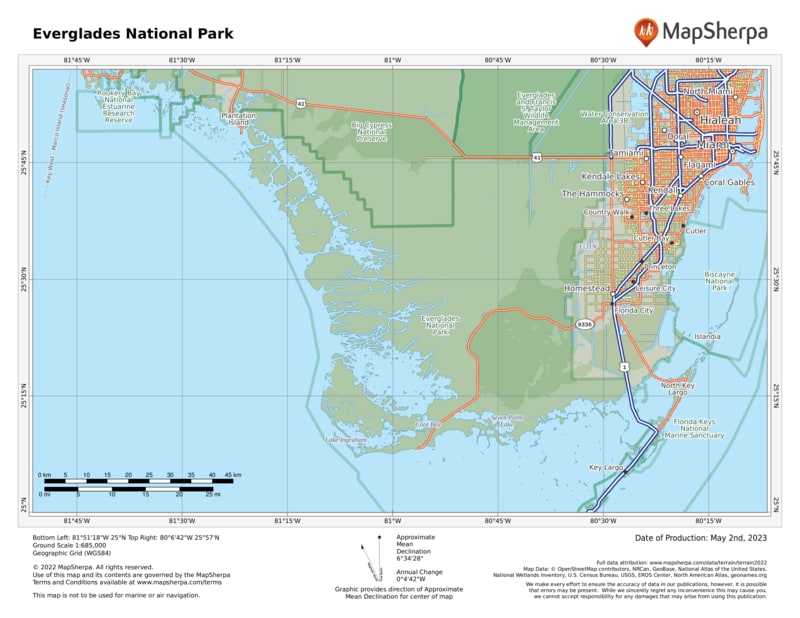

Drive to Everglades National Park from Florida City, along Fla. 9336, as most visitors do, and get a graphic lesson in conservation along the way. From residential and commercial areas, the highway passes by fields of squash, cucumbers, tomatoes, and strawberries, crossing canals that are part of south Florida’s complex water management program.

The park welcome sign marks a sudden and stark change in the environment, with a succession of natural habitats lying to the west. The 38-mile main park road winds through subtropical hardwood hammocks, pinelands, groves of bald cypress, mangrove forest, and the great “River of Grass,” the sheet of freshwater that originally flowed from the southern shores of Lake Okeechobee through sawgrass across central Florida and out to Florida Bay.

As expansive as the park is, it represents only about one-fifth of the original Everglades ecosystem. Much of the rest has been destroyed or greatly altered for agriculture, urban and suburban growth, and water supply for some eight million area residents. People need places to live, as well as food and water, but the development of southern Florida has come at a great price.

Once, water flowed seasonally from the headwaters of the Kissimmee River, 200 miles north, down through Lake Okeechobee and the greater Everglades, continuing to Florida Bay. Water-management systems designed to protect from flooding during hurricanes disrupted this eons-old pattern, resulting in the degradation of large areas of natural landscape and the decline of wildlife populations. In addition, changes in water flow have threatened the underground aquifer that provides drinking water for Miami and other cities and towns. Concern over these issues led to the massive Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), a decades-long, multibillion-dollar project to address water problems over an 18,000-square-mile area commonly called “the Everglades.”

CERP has given new hope to conservationists and planners who have long worked to preserve the Everglades and protect the natural resources of the national park. Water flow has been improved, and there are signs that populations of wading birds such as wood storks are making a comeback. In 2014 the species was downlisted from endangered to threatened.

Yet there are new threats to the greater Everglades ecosystem in the form of introduced non-native species of plants and animals. The Brazilian pepper tree, for instance, has taken over large areas to the exclusion of native vegetation, and an influx of huge, predatory Burmese pythons has caused a dismaying loss of raccoons, rabbits, and foxes. Oscars, tilapia, and other alien fish displace native species in many areas.

Despite problems, the park remains one of America’s great nature experiences. From crocodiles to butterflies, palms to orchids, the subtropical Everglades environment offers rewards unique in North America.

How to Visit

Visitors explore on foot, by bicycle, or via canoe or kayak. Also available are guided tram and boat tours. The park’s vastness may tempt you to rush through in an attempt to see as much as you can. Resist the urge.

Most visitors arrive sometime during December to April, when heat, humidity, and insect activity are down. Birds, alligators, and other animals are concentrated in smaller, dry-season wetlands and thus are easier to see.

Despite its huge size, the park has only three main hubs for visitation, and two of them have limited activities. If you have only a short time, you may need to choose one area to explore. The best one-day tour begins at the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center, west of Homestead, and follows the main park road to Flamingo, where you’ll find another visitor center and a roster of ranger-led activities.

Everglades National Park is a little more subtle than most parks. To get a sense of it takes time. Go to the park at dawn or stay until dusk to enjoy the best wildlife activity. Stop for a while on a quiet trail or backcountry waterway, watching and listening.

Ranger-led programs reveal aspects of life here that might otherwise be overlooked. Learn about this rich and intricate ecosystem and you’ll understand why the park has been officially designated an international biosphere reserve, a World Heritage site, and a wetland of international importance. Everglades National Park has taken its place among the planet’s greatest natural areas.

Stop along the way to walk one or more of the interpretive trails.

The Anhinga Trail at Royal Palm is deservedly famous for wildlife viewing. With more time, take a boat tour at Flamingo or rent a kayak and paddle around Florida Bay

With even more time, consider a tram tour or bicycle ride through Shark Valley, in the northern section of the park (25 miles west of the Florida Turnpike in Miami, on U.S. 41 on the Tamiami Trail). Activities offered at the Gulf Coast Visitor Center in Everglades City, in the far western part of the park, focus on the water, with guided boat tours and canoe and kayak rentals for day trips or camping out in the Ten Thousand Islands area.

Useful Information

How to get there

To reach the main park entrance from Miami, FL (about 50 miles north), take Fla. 821 (Florida’s Turnpike) south to Florida City and then go west on Fla. 9336 (Palm Dr.). The Shark Valley area is on U.S. 41 about 40 miles west of downtown Miami, and the Gulf Coast Visitor Center is another 40 miles west; from there, head south 4 miles on Fla. 29.

When to go

There are two seasons: a wet summer and a dry winter. May through Nov. the weather is hot and humid; mosquitoes can be extremely bothersome. Ranger-led tours and other activities are limited in summer. Dry-season visits are generally more pleasant (though more crowded), with a March through April visit usually best.

Visitor Centers

Three visitor centers (Ernest F. Coe in the east, Shark Valley in the north, and Gulf Coast in the west) are open daily year-round. The Flamingo Visitor Center (southern tip of the park) is staffed intermittently mid-April to mid-Nov. but fully operational the rest of the year.

Headquarters

40001 State Road 9336 Homestead, FL 33034 nps.gov/ever 305-242-7700

Camping

Reached via the main park road are Long Pine Key Campground (108 sites; recreation.gov; 877-444-6777) and Flamingo Campgrounds (235 sites; flamingoeverglades.com/camping; 855-708-2207). The park also offers primitive backcountry camping (permit required). Most backcountry sites can be reached only by boat, but a few are accessible to hikers.

Lodging

Lodging is plentiful in Homestead and Florida City, just east. Lodging also can be found in Everglades City, just northwest. Tropical Everglades Visitor Association (tropicaleverglades .com; 305-245-9180).