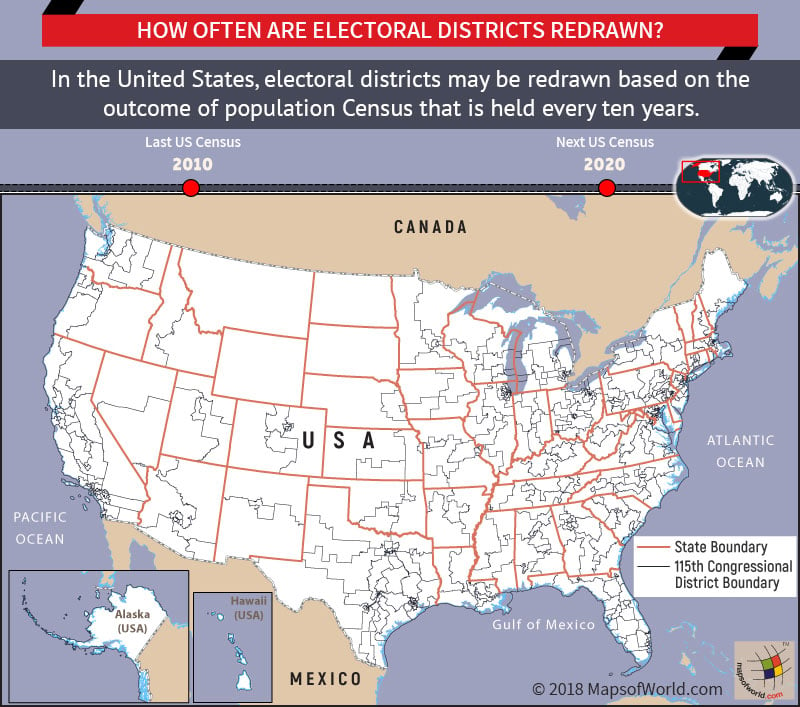

How often are electoral districts redrawn?

In the United States, electoral districts may be redrawn based on the outcome of the population Census that is held every ten years. The number of congressional seats apportioned to each state is determined based on the results of the census. The last U.S. Census was carried out in 2010, and the next is due in 2020.

In the United States, electoral districts may be redrawn based on the outcome of the population Census that is held every ten years. The number of congressional seats apportioned to each state is determined based on the results of the census. The last U.S. Census was carried out in 2010, and the next is due in 2020.

The federal criteria for redrawing district lines

- Equal population

- Race and Ethnicity

The state criteria are

- Political territory

- Contiguity

- Communities impacted

- Political outcomes

Why are electoral districts redrawn?

In previous years, rural counties with smaller populations had greater representation than towns and cities with higher population. States were reluctant to redraw districts since business feared dilution of wealth and control. As the population expanded, so did the imbalance in people’s representation. To counter this imbalance, the Supreme Court passed several rulings in different cases related to the need for redistricting.

Since population increases over time, it became necessary to redraw districts that reflect the addition to the voting population. Based on the Census data outcomes every ten years, state legislatures, and in some cases redistricting commissions, are mandated with the responsibility of identifying and carrying out the process of redrawing state legislative and congressional districts. The objective is to ensure all citizens in every state get equal representation through the new district realignment. The approach to redrawing districts varies for each state.

Article 1, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution, states the seats in the House of Representatives be apportioned among the states to reflect the shift in population recorded through Census every ten years, with every state entitled to at least one representative to the House.

Landmark rulings related to redistricting

The Supreme Court has passed several rulings related to the subject covering four broad areas

- Population

- Redistricting Commission

- Race

- Partisanship

Population:

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962): It was ruled that federal courts had the jurisdiction to challenge redistricting plans by state legislatures.

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963): The ‘one person, one vote’ principle was made constitutional standard.

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964): Redistricting of legislative districts to be carried out every ten years.

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964): Malapportionment was against the Constitution; courts had jurisdiction to rule on any challenges to the congressional districts drawn up by states.

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973): Ten percent deviation in population would be the threshold for justifying or challenging the redistricting plans of the state.

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983): All congressional districts must mathematically represent an equal population.

Evenwel v. Abbott, 578 U.S., 136 S. Ct. 1120 (2016): Total population to be the reference for confirming compliance to ‘one person, one vote’.

Redistricting Commission

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, No. 13-1314, 576 U.S., 135 S. Ct. 2652 (2015): Allowed of establishing a redistricting commission to redraw state and congressional districts through ballot initiative.

Race

Beer v. the United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976): Preclearance to be denied only in cases of retrogression of minority opportunity and not any other form of discrimination, as per Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Since the subsequent ruling on Shelby County v. Holder, Section 5 became unenforceable.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986): The terms established to ensure no vote dilution takes place while determining justification for redrawing majority-minority districts.

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993): Redrawing of districts to be denied in cases of where irregularly drawn district plan reflects the possibility of racial intent.

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995): Equal Protection Clause was reinforced to prevent racial gerrymandering through redistricting.

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996): A new district plan must pass scrutiny for racial gerrymandering under Equal Protection Clause.

Shelby County v. Holder, No. 12-96, 570 U.S. (June 25, 2013): Redistricting plans and related voting laws do not require prior approval, as Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act was not applicable anymore to any jurisdiction in the U.S.

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, No. 13-895, 575 U.S., 135 S. Ct. 1257 (2015): Claims of racial gerrymandering to be taken up for each concerned district and not the entire state plan. Maintaining numerical minority percentage not mandatory for redistricting under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

Cooper v. Harris, No. 15-1262, 581 U.S., 137 S. Ct. 1455 (2017): Partisanship while drawing new district plans cannot be used to make a case for racial gerrymandering.

Partisanship

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973): A reapportionment plan may not be challenged if political fairness in proven.

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986): Claims of partisan gerrymandering was brought under Equal Protection Clause and could be referred to federal courts. The benchmark was established for determining whether redrawing district lines had an intention for discriminating against minority groups or not. However, this benchmark was later set aside in the Vieth v. Jubelirer case.

Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267 (2004): Claims of partisan gerrymandering remains justiciable although previous cases made proved it difficult. Four cases relating to this are pending in the Supreme Court.

Visit the following to learn more about the USA:

Related Maps: