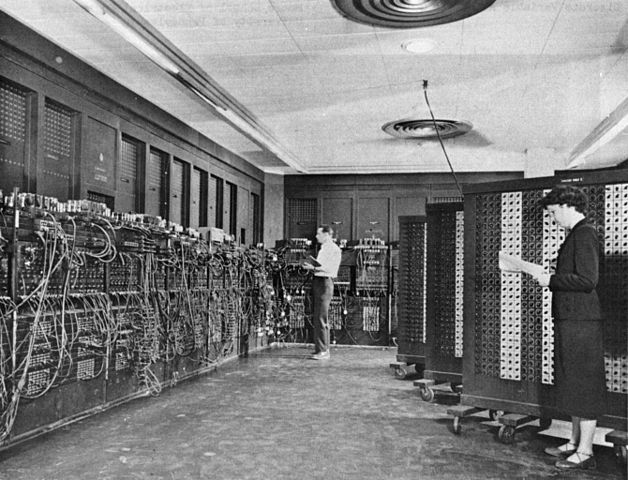

The Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), the world’s first fully electronic automatic “computing machine,” became public knowledge at a large public ceremony at the University of Pennsylvania on February 15, 1946. Weighing in at more than 27 tons and taking up 1,800 square feet, the “Giant Brain” represented a quantum leap in technology — more than 1,000 times more powerful than its predecessors — and heralded the coming of an age driven by computers seen throughout the world today. Though a dazzling sight to reporters on the scene in Philadelphia that day, the origins of ENIAC can be traced to the years before World War II. The United States military, a shadow of its former self after the horrors of the First World War, had little in the way of resources or manpower across the board — the US Army, for example, had only 190,000 soldiers and its Air Forces essentially did not exist. (By the end of combat, there would be 8.5 million troops and some 80,000 planes in the inventory.) Because of this vast unreadiness, just a few dozen officers and civilians were in charge of the Ordnance Department testing weapons and storing materials at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland some 70 miles northeast of Washington, DC. A small percentage of those on staff were dedicated to the Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL), tasked with determining the range and effectiveness of munitions to create reference tables used by soldiers in the field to suppress enemy movements with firing and bombing in all sorts of weather conditions. Those in the Ballistic Computing Section (BCS) worked tirelessly using basic desk calculators and a Bush Differential Analyzer, a primitive computer using a mixture of electrical impulses and mechanical stimuli, to produce results. Within months of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US ramped up the war effort beyond the capacity of the BRL. Even with the annexation of a second Bush Differential Analyzer at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering of the University of Pennsylvania, BCS teams were working around the clock to pull together calculations by June 1942. As officials from Aberdeen collaborated with academics in Philadelphia, the idea for an all-electric computing machine soon seemed a theoretical possibility. Using a grant from the US Army Ordnance Corps budget, Lt. Colonel P.N. Gillon officially contracted with the university’s Board of Trustees on June 5, 1943 desperate to believe the “electronic numerical integrator and calculator” proposed by two of Penn’s professors would work. Working with a team of engineers to create the six main components of the machine, the staff believed vacuum tubes could serve to drastically speed up the calculation process. A year later, the first piece of the gargantuan machine was in place, beginning a 16-month construction phase completed in the fall of 1945 — two months after World War II had come to an end. At a cost of more than $486,000, development of the ENIAC was one of the most expensive projects the US Army funded that served no direct purpose in fighting the Germans or Japanese. Consisting of 30 separate, boxy modules networked together by a complex system of nearly 5 million hand-soldered joints, the computer required 150 kilowatts of electricity, about the same as the weekly usage of a modern home. When revealed to the public on February 15, 1946, the results of “Project PX” astounded the gathered press. Capable of performing 5,000 simple calculations per second, a team of staffers — almost exclusively women, at the beginning — would spend several weeks turning switches and placing punched cards in a specific sequence before running the simulation. Capable of doing more than straightforward arithmetic, the full scope of which might take a single BCS staffer twelve hours to complete for just one test, once programmed the ENIAC could perform extensive variations on a formula in only 15 minutes. No longer at war, the US Army had to find a new use for ENIAC after it arrived at Aberdeen officially on July 29, 1947. When turned on that day, the machine began an eight-year run as the central computing processor for a variety of military programs, including the creation of wind tunnels for airframe testing, weather forecasting and even the development of the hydrogen bomb. With the exception of one five-day stretch in 1954, ENIAC ran nearly continuously. By the mid-1950s, as smaller and more powerful machines came on the market, the ENIAC was well obsolete. Parts of it are on display in museums all over the US, showing what was once the height of technology — an unthinkably slow machine compared to computers today that run as much as 33,000 times faster. Also On This Day: 1898 – The USS Maine sinks in the harbor of Havana, Cuba and leads the United States to declare war on Spain 1944 – The Allied assault on Monte Cassino, Italy begins 1965 – The current flag of Canada is adopted 1989 – The Soviet Union officially announces the last of the Red Army has left Afganistan 2001 – The first draft of the complete human genome is published in the scientific journal Nature You may also like : February 15 1898 – The USS Maine sinks in the harbor of Havana, Cuba and leads the United States to declare war on Spain

February 15 1946 – ENIAC is Dedicated at the University of Pennsylvania